| Touching Bases | November 19, 2009 |

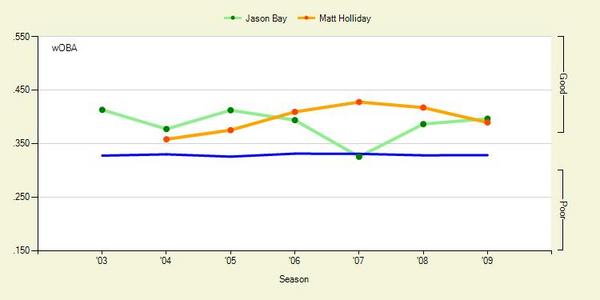

Jason Bay and Matt Holliday are the two best hitters on the market. Holliday is a year younger than Bay, and will likely command a more lucrative contract. If you'd like to know how they stack up in left field, check out ESPN's recent articles analyzing the matter. But I’d like to concentrate on their hitting. Here’s how they stack up, per FanGraphs

Over the past two years, they’ve been rather even hitters. Using 2008-09 pitchf/x data, I’ll take a deeper look

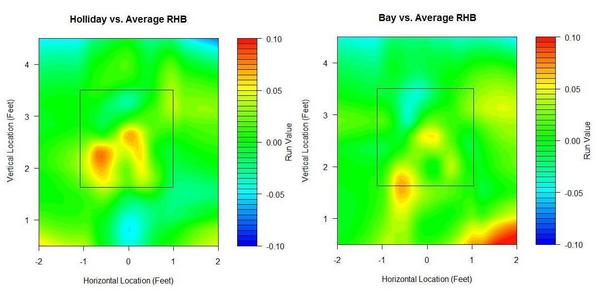

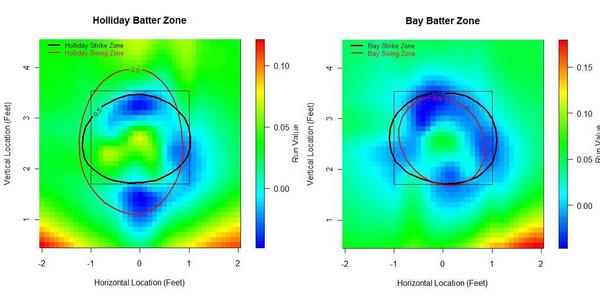

A couple weeks ago, I introduced a series of graphs that try to provide a visual scouting report of sorts for hitters. Here's how each batter performs by pitch location.

(Click on images to enlarge.)

They are strikingly similar compared to league average. Middle and lower in, they’re well above average, but they have weaknesses up and in. I'm surprised that hitters the caliber of Holliday and Bay perform worse than league average in any spots. Holliday also struggles more than the average batter on pitches down and out of the zone, while Bay appears to excel at pitches way down and away, likely a result of his excellent plate discipline.

No matter how I break these guys down, they'll turn out above league average at almost everything, so I prefer to compare them to themselves. The next set of graphs shows how they do relative to their own averages, as opposed to the league average. Therefore, every single batter will have some blue—even Pujols—and every single batter some red—even Tony Pena, and that's because every single batter has relative strengths and weaknesses.

Bay appears to have a great knowledge of the strike zone, as his “swing zone” and “strike zone” nearly overlap. (These contour lines indicate where the probability shifts from greater than 50% to less than 50%. For example, pitches outside the black elipse are more likely to be called for a ball than a strike, and pitches inside the red elipse are more likely to be swung at than taken.) Holliday, however, has a distinct region outside the strike zone where he owns a negative run value. This seems to stem from Holliday's propensity to expand the strike zone. Yet he doesn’t face the same problems up in the zone, even though he’s willing to swing at high balls too.

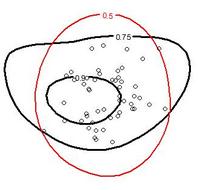

To look deeper into this, I plotted the same red 50% swing zone, and also included Holliday's contact zones at 75% and 90% intervals, which show where he's most likely to make contact when he swings. You can also see 50 separate points that indicate the location of pitches that resulted in Holliday's home runs.

What we're interested in is the very top and very bottom of his swing zone—the portions that extend beyond his strike zone. It turns out that these regions also extend beyond his 75% contact zones. There is slightly less area up top between his swing zone and contact zone as there is in the bottom region, meaning he is better at making contact on pitches at high pitches out of the strike zone than low pitches out of the strike zone. But he hasn't hit homers in either of those regions. He has swung half the time at these bad balls, and whiffed over a quarter of the time when he does pull the trigger. The most important thing to remember is that both of these swing-and-miss regions would be called for balls more often than not if he would just lay off.

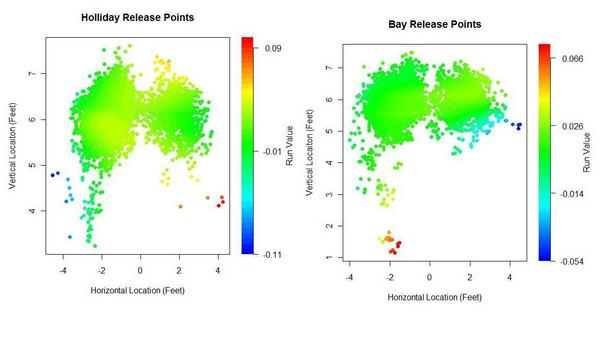

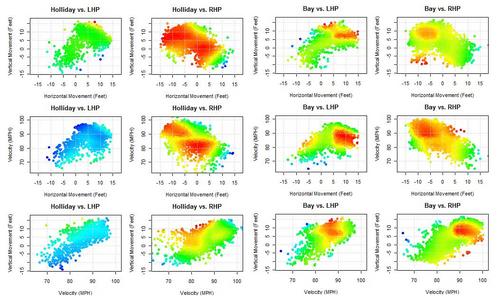

How about their platoon splits? I use release point data for these. Like the previous graphs, these are from the batter's point of view.

Bay exhibited a reverse platoon split two years ago, but over his career he has maintained a normal split. Normally I exclude Chad Bradford's release points, since they’re outliers, but I wanted to include them to show Bay’s success against submariners and sidearmers. He’s five-for-eight against Bradford in his career. Bay’s had less success against lefties with lower arm slots. He’s 0 for 16 with three walks against the likes of Brian Fuentes, Billy Wagner, and Javier Lopez. In 2009, Bay and Holliday both faced the highest rate of LHPs of their careers.

Now, I’m not sure if this next set of graphs will catch on, but I wanted to know how batters fare by pitch type, so here’s what I came up with. You have to have some knowledge of pitchf/x data to fully comprehend these graphs, but really all that I look for is to quickly see if there’s some type of obvious gradient from blue to red or red to blue that would suggest a batter does better against pitches of a certain velocity and break.

You can see very distinct sections in Bay's graphs where he excels against both LHPs and RHPs. These pitches have the same velocity and movement as your league average fastball (about 85-95 miles per hour with 5-10 inches of horizontal and vertical movement), which meshes with Bay's reputation as a fastball hitter. Over the past two seasons, Bay has been the fourth best hitter in baseball against the fastball. He’s not as good against curveballs, especially slower breaking pitches. I didn’t note anything remarkable in Holliday’s release point graphs nor his velocity/movement graphs, but Holliday does have interesting pitch splits. He saw 65% fastballs with the A’s and 55% with the Cardinals. In exchange, he saw his slider rate nearly double in St. Louis. The increase in slider percentage might have been part of the reason Holliday found renewed success, as he has been the top hitter in the Majors against the slider over the last two years.

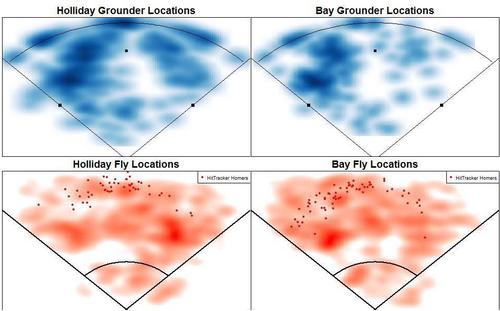

Finally, hit locations.

Holliday was shipped out of Coors Field in the offseason, and he might have felt the hangover effect, having tailored his game to Coors where he has boasted a career OPS 160 points better than he has at all other venues. Or a combination of Oakland's pitcher's park, increased quality of competition, and decreased slider percentage plagued him. Or the first half of the season was just noise. His BABIP shot up from a career low .318 in Oakland to a career high .391 in St. Louis. Once he was traded, he hit more line drives and fewer infield flies. Due to its spacious foul grounds, the Coliseum's park factor for infield fly balls is around 104. More importantly, Holliday's home run per fly ball rate was just 9.7% in the Coliseum, well below his career rate of 16.5%. The average batter would see his homes runs per fly ball plummet some 30% in a move from Colorado to Oakland. (Batted ball park effects from David Gassko.)

Meanwhile, Bay pulls balls at an extraordinary rate. Infielders should shift him to the pull side as much as is acceptable against right-handed batters. He pulls his fly balls at a high rate too.

Meanwhile, Bay pulls balls at an extraordinary rate. Infielders should shift him to the pull side as much as is acceptable against right-handed batters. He pulls his fly balls at a high rate too.

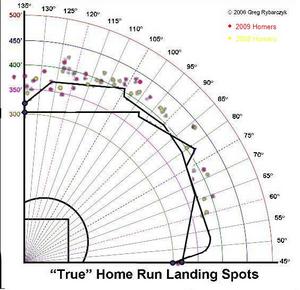

Bay was traded to a haven in Fenway Park, where he could take advantage of the green monster in left field. Using Hit Tracker Online data, I plotted Bay's 2009 homers against his 2008 homers along with Fenway's and PNC's outfield dimensions.

15% of Bay's balls in play last year were fly balls to left, compared to 10% in 2008. Could this have been a conscious effort? In 2008, 43% of his flies to left were hits and 25% were homers. In 2009, 63% of Bay's flies to left were hits and 40% were homers. Thanks to the monster, He managed more more homers on flies to left last year than he had all of hits on flies to left two years ago. I'm sure the trade-off in opposite-field power for pull power yielded a net positive for Bay.

As always, these graphs are works in progress, so please feel free to leave comments on how to improve them.

Comments

Great stuff, Jeremy. I particularly love the Holliday strike zone graphs.

Posted by: studes at November 19, 2009 4:23 AM

Terrific graphs and observations. Excellent visual scouting reports.

Posted by: Rich Lederer at November 19, 2009 6:25 AM

So Jason Bay can only hit fastballs? only twelve homers came off off-speed pitches last season and 4 out of 28 in 2008.

Posted by: RZ at November 19, 2009 11:57 AM