| Designated Hitter | October 10, 2011 |

A friend of mine, Ross Moskowitz, is the director of Camp Westmont, a beautiful summer camp in the Pocono Mts. of Pennsylvania. It's the kind of place every kid should be able to attend at least once in their lives. He's also a baseball man. Played Division One NCAA baseball at the University of Maryland. So when he told me that John Denny was going to be his baseball instructor this past summer, I thought it would make for a very interesting story/interview. How does a good pitcher become the best pitcher in the world for one season and win the Cy Young award? From Bob Turley to Randy Jones to Mark Davis to Pat Hentgen, just to name a few, there have been a bunch of pitchers who've taken that step.

I spent a morning with John Denny at the end of August. He's 58 years old now and has kept in great shape. Simply put, he's one of the nicest, soft-spoken people I've ever met. Aside from working for the Arizona Diamondbacks for a few years, he hasn't had that much to do with Major League Baseball since he retired in 1986. Like most former ballplayers, he has a amazing memory of games, players, even specific at-bats from 25-35 years ago. He's also quite introspective about himself and his place in the game's past. His response to my question "So you won Game One of the 1983 World Series?" was unexpected. "Yeah, how about that," as if he still couldn't quite believe his good fortune. We went off topic at times, but his stories about his Hall of Fame teammates were worth hearing. I turned on the tape recorder.

David: In looking at your career, the numbers tell a story of a pitcher with obvious talent, twice leading the NL in ERA, who would follow those seasons with quite a few off years. Were injuries a major factor?

John: Injuries were a big problem for me. My rookie year, 1975, I started the season 2-2 for St. Louis, they sent me back to Triple-A for a month. When I came back, I won seven games in a row, I'm 9-2 and some people were talking about me as a Rookie of the Year candidate. One day, I'm jogging in the outfield in Cincinnati and I tore a lateral ligament. We were only a few games out of first, so I pitched through it and wound up 10-7. The next year, 1976, I was healthy and led the league in ERA (2.52). Then, in 1977, I started the season 7-0 and I strained my hamstring covering first base, then tore that hamstring at Dodger Stadium. And I wound up going 8-8. 1978, I was healthy again and had another good year (14-11, 2.96 ERA).

David: Who was your manager with the Cards?

John: Red Schoendeinst was my first manager, then Vern Rapp and finally Ken Boyer. This was right before the Whitey Herzog era. I would've loved to have played for Whitey, but I was traded to Cleveland. But I loved my time in St. Louis. I played with Joe Torre, Bob Gibson and Lou Brock. They were true professionals and some of that rubbed off on me.

David: So you go from a great baseball city to playing in Municipal Stadium?

John: It was tough. That park seated 80,000 people, so even if we had 40,000 people in the stands, which we rarely did, it was half empty. And I think that affected a lot of our players. We had a good rotation. Bert Blyleven, Rick Sutcliffe, myself, Rick Waits, who won 15-16 games one year. Later, Len Barker. After a few years, I became a free agent while with Cleveland. And George Steinbrenner offered the world to me, but I turned him down.

David: I never knew that.

John: My agent handled it all. I never met Steinbrenner, but his quote the next day in the newspapers was something like "John Denny will never wear a Yankee uniform as long as I'm alive." I would've loved to have played for the Yankees, but word was he was very interfering, came down to the locker room all the time. I didn't think I could play for an owner like that.

David: I've never been shy about my feelings for him. I believe he demeaned the game more than anyone in my lifetime. Younger people, especially Yankee fans, forget just how hated he was in New York until they started winning again in 1996.

John: Well, he offered me the best contract with wonderful perks and opportunities for the future. I would've been way better off financially. But my thinking was I worked very hard and I played the game very hard. And I pictured myself working my butt off, putting every ounce of energy I had into the game. I was a thinking pitcher and I studied the hitters. And I pictured if things weren't going well, he'd call me into his office and air me out. And then go to the papers and tell them what he just did. I didn't want to put myself in that situation. And I eventually wound up with the Phils and I loved my time there. I missed almost the entire 1982 season, but then got involved with a strength and flexibility coach that Steve Carlton recommended and he helped me enormously.

David: Before we get to your time with the Phils, let me ask you, "Who was your toughest hitter to face? Who lit you up?"

John: Easy, Tony Gwynn. His pitch recognition was incredible. So I'd make some adjustments and the minute I thought I had him, he'd make adjustments too. Always one step ahead of me. As time went on, I thought I was starting to figure him out. If he had a weakness, it was inside. But you couldn't live in there. The moment you thought you could pound him inside, he'd make that adjustment and take you deep. So I'd go to my sinking fastball and start to pitch him away, but he used to take that to left field really well.

David: How was Willie Stargell to face?

John: I don't know what my actual stats against him were, but I'll tell you this story about Stargell. I was pitching in Pittsburgh one night and I threw him a fastball, down and away. He turned that sucker around right up the middle. I could hear that ball singing as it went by me. It short-hopped the fence in left center for a double. He hit it so hard and I remember thinking to myself that ball might've killed me. From then on, I pitched him only inside and I didn't care if he hit it five miles. He was a true professional too, an old school guy and I was a newer type of player. And I learned so much from the old schoolers.

David: Who else?

John: Pete Rose. I pitched a great game one night with St. Louis against the Big Red Machine — Monday Night Game of the Week. The next day he calls me over before our game. I'm 23 years old and I'm wondering what does Pete Rose want to talk to me about? He says "John, I just want to tell you last night you threw one hell of a ballgame. Your fastball was in on my hands all night. But I'll tell you something, next time I'm gonna get you good, you S.O.B." More than anyone, he helped show me how to be a professional and still show respect to the other team and the other players and still be the man and the player you need to be.

David: Let's talk about the 1983 Phils and your Cy Young season. Who was your pitching coach there?

John: Claude Osteen, who had been my teammate and pitching coach with the Cardinals. He was the perfect pitching coach for me.

David: The 1983 Phils are one of my favorite teams. The team had started to age quite a bit, had a lot of veterans, Schmidt, Carlton, Rose. Then they get even older by adding Joe Morgan and Tony Perez at the end of their careers and they win the pennant. Remarkable story.

John: They called us "the Wheeze Kids." (The 1950 pennant winning Phils were called the Whiz Kids).

David: Right. Now, obviously, you were healthy. Did you add a new pitch, change your motion?

John: No, but a few things happened. First, I was in great shape, the best of my career. I had started working out with a strength and conditioning coach, Van Hoefling. He had been with the Los Angeles Rams and when Roman Gabriel was traded to the Eagles, Van followed him to Philly. And Lefty and I got involved with him. And he was great for me. But no new pitch or motion. I was basically a fastball, curve pitcher. And I could add some sink or movement to both of them, so I guess I threw four pitches.

The biggest difference was that I was playing on a team with guys who knew how to win and it rubbed off on me.

David: It was attitude?

John: Attitude and being in great shape. Here's one example and this is what I loved about Pete Rose. I'd get two strikes on a batter and I'd hear him yell or whistle from his position at first base. "You got two strikes on this guy, you know what to do." Because you never want to lose a batter with two strikes on him, you need to finish him off. And Rose was the kind of guy who pounded it home. Just like his career. He took the talent he had and pounded it home, never let up. He stayed on me all year. I am so blessed I was able to play with him. And Lefty and Schmitty and Morgan and Perez too.

Lefty and I had lockers next to each other. Talk about two different guys. I was a Christian and he believed in Eastern religions, mysticism. But we were so close, worked out in the offseason together. One time I said to him, "Lefty, I've never thrown a slider in my life, show it to me." So he held the ball up, put his hand up and says "I just turn my wrist a little bit like this and I throw the shit out of it." (Laughter).

He had great catchers in Bob Boone and Tim McCarver who got to know him as well as he knew himself. I don't recall Lefty shaking off many pitches. And it was a combination of three things. I know what I'm doing out here, I really don't need to take charge because my catcher is handling it very well and I know I can throw what they want.

David: What a huge advantage for a pitcher.

John: Oh yeah. One of the things I tried to do was not to get into a disagreement with any catcher. If he's calling for a fastball down and away and I want to throw up and in, I would say to myself "What the heck, I can throw down and away and still get this guy out." And it made me a better pitcher and it also made my catcher better too because now he knows that I trusted him and then they would work even harder and call a better game." And Lefty had his catcher's trust and that's huge.

David: What was it like in 1983 to look behind you and see Rose at first, Morgan at second and Schmidt at 3rd?

John: You know, the first real ballgame I ever saw in my life, I was ten years old (1963) and my Little League coach, who I still stay in touch with, he was like a father figure to me, took me to Los Angeles from where I was born and raised in Arizona.

David: Were you a Dodgers fan?

John: Well, actually I used to listen to the Giants all the time because I could get KNBR radio very well where I lived. Willie Mays was my favorite player. So he took me to a Dodgers/Giants game. Juan Marichal and Don Drysdale and the Dodgers won 1-0 in the bottom of the 9th inning. I can still remember Marichal throwing that incredible overhand curve for a strike with that big leg kick. So at 10 years old, I get to see two great Hall of Fame pitchers in this great pitching duel and in 1983, I get to play alongside five Hall of Famers.

Now we played mostly on Astroturf back then. Perez, Morgan and Rose were all on their way out, had already lost a step, but anytime there were runners in scoring position, they'd always dive for balls. They saved me run after run after run. They always gave it everything they had and we won the pennant that year to a large degree because of their professionalism. And that leadership rubbed off on Schmitty and we desparately needed that because he could be quite volatile. The fans could really get on him.

David: Give me an example of Schmidt's leadership.

John: I was pitching against Nolan Ryan in Philadelphia. I was down 2-1 in the bottom of the 8th. Ryan was so unhittable that day, throwing darts. Top of our order, he goes through the first two guys. Garry Maddox or Gary Matthews, I can't remember which, draws a walk. Schmitty comes up and Ryan had been making him look terrible all day. Schmitty had no chance. Ryan was on the attack the whole game — attack, attack. He goes 3-2 on Schmitty. And Schmidt would always try to analyze what pitch was coming. Everyone on the bench was hoping for a fastball, because if Ryan dropped that hook on him, he had no chance.

Ryan was grunting on every pitch, never saw anyone throw harder than he did that day. He was so intimidating. Fastball. Ball landed in the second deck and we won the game 3-2. Now that's talent, but it's also leadership because Schmitty knew no one else on our club could touch Ryan that day. It was up to him.

David: So you win the pennant and you win Game One of the World Series?

John: Yeah, how about that.

David: Was the game at the Vet?

John: No, it was in Baltimore, won it 2-1, beat Scott McGregor. I gave up a home run to Jim Dwyer, who was my minor league teammate on the Cardinals, pitched well rest of the game. Only game we won.

David: 19-7, 2.37 ERA, Cy Young Award, win a World Series game.

John: Pretty great year to live through.

For the past 30 years, David Bromberg has lived in Northeast Pennsylvania, former home of the Scranton/Wilkes Barre Red Barons (Phils Triple A team) and current home of the S/WB Yankees Triple A team. He was dubbed "the most inveterate baseball fan in northeast Pa. by Ron Allen, who hosted the local nightly sports radio call-in show there.

| Designated Hitter | June 13, 2011 |

The recent death of Harmon Killebrew prompted many touching reminiscences about a man with seemingly no enemies, despite carrying around the nickname of “Killer” for most of his life. (He did not really need a nickname; both his first and last names are unique in major league history.) By all accounts, he was a gentle and loving person, who also happened to hit home runs more frequently than anyone of his time. He hit 45 or more round trippers six times in the 1960s, while no other American League batter did it more than once. For baseball fans of a certain age, no player will ever better personify the word “slugger.”

Another interesting thing about Killebrew, perhaps unique among Hall of Fame players: he was repeatedly shifted between three defensive positions throughout his career, getting 44% of his starts at first base, 33% at third base, and 22% in left field. While many players shift positions along the defensive spectrum as they age, moving from shortstop to third base, or from left field to first base, Killebrew’s managers shifted their star hitter, nearly to the end of his career, depending mainly on the other players on the team. (It would be as if Tony LaRussa started playing Albert Pujols at third base. Oh, wait …)

Let’s review:

1954-58. Forced to start his big-league career early because of the bonus rule, Killebrew spent parts of five seasons as a little-used infielder for the Washington Senators.

1959. Having traded Eddie Yost, manager Cookie Lavagetto gave Killebrew the third base job. Harmon responded with a league-leading 42 home runs, and started his first All-Star game.

1960. Harmon remained at third until mid-season, when Lavagetto decided he needed to get Reno Bertoia into the lineup (or Julio Becquer out of it) and shifted Killebrew across the diamond to first base.

1961. With the franchise now in Minnesota, Killebrew spent the first half of the 1961 season splitting time between first and third, until Sam Mele became the skipper in mid-season and kept Killebrew at first. (I am not going to recite lots of offensive statistics, so just go ahead and assume that Killebrew hit 45 home runs and batted .260 with a bunch of walks, since he did that every year.)

1962. Just prior to the start of the 1962 season, the Twins acquired Vic Power, a great defensive first baseman, and moved Killebrew to left field for the first time.

1963. Left field.

1964. Left field. Tony Oliva took over in right field in 1964, and Power was discarded early in the season, creating a perfect opportunity to get Killebrew back to first base. Instead Mele shifted Bob Allison and left Killebrew in the outfield.

1965. Killebrew moved to first base (and Allison to left), but Harmon began shifting to third often by mid-season so that the team could play Don Mincher against right-handed pitchers. In early August Killebrew hurt his arm during a collision (while playing first base), but returned in September and played all seven games—at third—in the World Series.

1966. He played all 162 games, moving between third base, first base, and left field depending on who else Mele wanted to play. The Twins also had Cesar Tovar playing all over the field, leaving Mele about seven million possible defensive alignments. Tovar played this role for several years.

1967. Mincher was traded to the Angels, allowing Killebrew to play a full season at first base (160 games) for the first time in his career.

1968. A full-time first baseman again, Killebrew ruptured his hamstring in the All-Star game stretching for a throw on Houston’s AstroTurf (which was blamed at the time for the injury). When he returned in September Rich Reese had taken over at first, so manager Cal Ermer put Harmon (recovering from a severe injury) back at third base to play out the season.

1969. New manager Billy Martin took one look at the 33-year-old slugger coming off major surgery, and decided to return Killebrew to the 3B-1B role, allowing Martin options at the other corner spot. Harmon started all 162 games (96 at third base, 66 at first), drove in 140 runs, and won the MVP award, while the Twins nabbed the inaugural AL West title.

1970. Martin was replaced as skipper by Bill Rigney, who made Reese more of a full-time player. Killebrew started 129 games at third, but still managed 26 back at first.

1971. Killebrew again played both corner spots, though Reese’s poor season (.219) gave Killebrew several long stretches at first, where he started 82 times.

1972. For the first time since 1958 (when he played just nine games in the field), Killebrew played just one defensive position, first base. He was 36 and had slowed down quite a bit, though he could still rake (138 OPS+).

1973-75. With the advent of the designated hitter, the elderly Killebrew seemed to have a ready-made role. Unfortunately, the Twins also had a hobbled Tony Oliva, who needed the role even more. Killebrew eventually made it to DH, but spent his final three seasons fighting injuries and ineffectiveness.

OK, so the question is: how much defensive value did Harmon Killebrew have? According to bWAR, Killebrew’s cumulative defensive value was -7.6 wins, meaning that his place on the field cost his teams nearly 8 games on defense when compared with a replacement level player. Killebrew was a big guy, not fast, and no one ever accused him of being a good glove man. On the other hand, one wonders whether he could have been better on defense had he been allowed to play one position (preferably first base) for 15 years.

More importantly, did Killebrew’s ability to play multiple positions, often day-to-day, provide additional value to his team? In 1969 Martin played Harmon at third base 2/3 of the time so that Rich Reese could play first base. In an otherwise undistinguished career, Reese hit .322 with 18 home runs (good for a 139 OPS+), Killebrew had his best year, and the Twins led the league in runs. According to bWAR, Harmon’s (mostly) third base play cost the team 1.3 games on defense. This might be true, and Harmon’s isolated value might have been better had he just played first base all season and let Frank Quillici or someone play third. In order to get Reese’s bat in the lineup (or Mincher’s, Power’s, or Bertoia’s), Killebrew was asked to play a position he could not play particularly well.

It seems to me that Killebrew’s “value” to the Twins might have been greater than his statistical record might show.

Another player shifted around the diamond throughout his career was Pete Rose. Unlike Killebrew, Rose did not move day-to-day—he stayed in one place for several years before moving on. Also unlike Killebrew, Rose was an outstanding defensive player for part of his career, before being asked to move again. Rose came up as a second baseman in 1963, then moved to left field (1967), right field (1968), left field (1972), third base (1975), and first base (1979). Let’s examine his move to third base.

Rose won two Gold Gloves in right field, where he had good range though only a fair arm. He was moved to left field in 1972 largely in deference to Cesar Geronimo, a great defensive player with a cannon. In left field, Rose was outstanding. How outstanding? According to the defensive runs metric used on baseball-reference.com, here are the best outfielders in baseball over the years 1972-74, in aggregate.

Pete Rose 52

Paul Blair 52

Cesar Geronimo 34

Bill North 30

Bobby Bonds 26

Other than Rose, these are all center fielders. As a hitter, Rose trailed only Willie Stargell, Cesar Cedeno and Reggie Jackson in batting runs among outfielders, making him every bit as valuable as he was famous.

Nonetheless, in May 1975 Sparky Anderson moved Rose to third base. The effect on the Reds was to replace third baseman John Vukovich, hitting .211 with zero home runs, with left fielder George Foster, who would hit .300 with 23 home runs. Rose continued to hit as well as ever, and the team won 108 games and the World Series.

Over the 1975 and 1976 seasons combined, Rose had the sixth highest total of batting runs in the major leagues, but rather than being worth two wins per season on defense (as he had been in left field) he was now worse than replacement level. Meanwhile, George Foster became a star and the Reds won two championships. Anderson could have moved Foster to third base, but he thought Rose could handle it. Given what happened to the Reds, I am forced to conclude that Anderson knew what he was talking about.

So, what am I saying? I am not saying that there should a new statistic to measure flexibility, nor am I suggesting that the WAR values we have become familiar with are wrong, or should be adjusted. I am saying: assessing “value” is complicated.

Mark Armour is a baseball writer living in Corvallis, Oregon, and the director of SABR’s Baseball Biography Project. His book Joe Cronin: A Life in Baseball was published in 2010 by the University of Nebraska Press. He and Dan Levitt are working on a sequel to their 2003 book Paths to Glory.

| Designated Hitter | April 20, 2011 |

I snuck out of work a little early to catch the biggest headliner Southern California had to offer this past Friday. No, I’m not talking about The Black Keys or Kings of Leon, two of the biggest acts performing at Coachella, one of the largest and most popular music festivals west of Rosenblatt Stadium. Instead of driving 130 miles east to Indio, I headed 30 miles north to Jackie Robinson Stadium, home to the 23rd-ranked UCLA baseball team and the stage of the country’s top amateur pitching – if not overall – prospect, Gerrit Cole. The Bruin righty was set to toe the rubber against Pac-10 rival and 20th-ranked University of Arizona Wildcats.

I knew the drive from Huntington Beach to Los Angeles would afford me time to listen to some tunes, so I prepared the trip with a “2011 Coachella” playlist, chock-full of the weekend’s performers. What follows is a breakdown of Cole’s performance along with concurrently performing acts from Coachella’s Friday set times.

4:28 PM – Ozomatli, “City of Angels”

But see we’re living in LA

And what you thought was the sun

Was just a flash from the K

Living within walking distance of Long Beach State’s Blair Field, I’ve been lucky enough to watch the collegiate careers of such hurlers like Jered Weaver (Long Beach State), Ian Kennedy (USC), and Ricky Romero (Cal State Fullerton), to name a few. While living in San Diego, I also checked out Friday night starts by Stephen Strasburg (San Diego State) and Brian Matusz (University of San Diego). I was excited to add Cole to the list of college arms I’ve witnessed up close.

Cole, who checks in at 6’4” and 220 pounds, is expected to be one of the first two picks in this June’s draft, improving on his 28th-overall selection by the Yankees in the 2008 draft. With what many consider three - if not four - “plus” pitches, Cole ranks third all-time (321) on the UCLA career strikeout list, trailing only former Bruin Alex Sanchez (328) and teammate Trevor Bauer (354).

I promised my buddy Jason, who I’m meeting for tonight's tilt, that I’d be there early so we could watch some of the pre-game action before the crowd arrives. Jason, being a University of Arizona alum, is just as excited to see sophomore Kurt Heyer pitch as I am to see Cole. Heyer, U of A's Friday night starter for a second-straight season, ranks third in the nation in strikeouts, so a low-scoring affair could be in the cards tonight.

5:46 PM - Ariel Pink's Haunted Graffiti, "Flashback"

Everyone was lurking on the streets

Always searching, always meeting for some action

Getting near the satisfaction

Well, so much for getting to sneak an early peek at Cole. I finally roll into the parking lot of Jackie Robinson Stadium with only a few minutes to spare before the 6:00 PM first pitch. Coincidentally, Friday's game marked the 64th anniversary of Jackie Robinson breaking Major League Baseball's color barrier and a few minutes before game time, this tidbit was brought up by the public address announcer, to which the entire crowd greeted with cheers.

As I made my way to the ticket booth to meet Jason, I feared that the turnout for this game was going to be pretty good, which should be expected for a Friday night game between two ranked teams and a legitimate college star on the mound. I was worried that a seat behind the plate among the scouts was out of the question, but as Jason and I walked up the steps along the first base line to the concourse, we were both pleased to see most had put their general admission tickets to use behind each teams' respective dugouts. We made our way to the third row, where I promptly set-up shop, doing my best "amateur scout scouting amateurs" impression.

Notepad, check. Game notes, check. Team stats from collegesplits.com, check. Stop watch, check. iPhone in camera mode, check. Stalker radar gun, no dice. But the two guns directly in front of me and the one next to me would work just fine.

6:14 PM - Ms. Lauryn Hill, "Everything is Everything"

It seems we lose the game

Before we even start to play

As we watched Cole toss the last of his warm-up pitches to begin the game, Jason turned to me and said "My Wildcats don't have a chance." I nodded in agreement, as Cole's delivery was anything but max-effort. Working from the far leftside of the rubber, his fastballs flew out of his right hand (three-quarter slot) with ease while registering a ho-hum 94 and 95 on the radar gun in front of me. The rest of Cole's body (athletic with a thick lower torso) followed right behind in a repeatable, smooth delivery.

Cole started the game as well as one could, striking out the first two batters looking and swinging, respectively, then getting catcher Jeff Bandy to fly out to shallow left-center.

As Heyer took to the hill and started his sequence of warm-up pitches, I noticed a stark difference between the two pitchers’ motions. Heyer, who’s listed at a generous 6’2” and 200, has a not-so-fluid, dipping motion towards the plate. “Looks like [Roy] Oswalt,” Jason says, and he’s right. Heyer’s velocity doesn’t look overly impressive, so I’m guessing his funky delivery, movement on pitches and ability to spot the ball are the factors leading to his mounting strikeout totals.

Not to be outdone by Cole, Heyer retires the side in order: ground-out, strikeout looking, strikeout looking. “Maybe we do have a chance,” Jason tells me as Heyer hops over the first base chalk line toward the Arizona dugout.

6:26 PM – YACHT, “It’s Coming To Get You”

It’s coming to get you

It’s coming to get you, get you

It’s coming to get you

Cole starts off the top of the second by throwing a 96-mph heater on the outside corner of the plate. There is a buzz around where we are sitting, as the scouts compare radar gun readings and scribble down notes after every pitch. It seems Cole has more guns pointing at him than Mussolini.

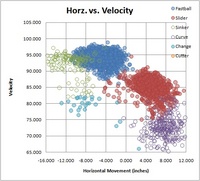

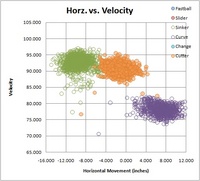

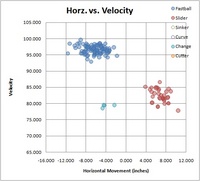

Cole breezes through the inning and the heart of the Arizona order, fanning two and getting a third to pop out in foul territory behind first base. Cole’s using his fastball to blow past hitters for strikes and also set them up to look silly when he unleashes his slider and change-up, both arriving at the plate with the same velocity (87 MPH) but with much different action: the slider travels on a more horizontal plane while the change-up seemingly adds weight a few feet from the bat and suddenly disappears from view.

6:58 PM – Afrojack, “Take Over Control”

I want you to take over control

Take over control

Take, take, take, take over control

At this point, Cole’s velocity on his fastball has been consistent and impressive, but not overpowering. He is, however, mixing his pitches well and keeping the hitters off balance, working the ball mostly on the inner and outer parts of the plate. Any mistakes seem to miss high with the fastball and away to right-hand hitters with his off-speed pitches. Cole has thrown quite a few balls out of the strike zone at this point but Arizona hitters haven’t been helping themselves, either fouling off the pitches or swinging and missing altogether. While calling Cole wild this early in the game would be unfair, he’s been effective while missing the plate.

With the game still scoreless in the top of the third inning, a Cole slider catches a little bit too much of the plate and Arizona’s Seth Mejias-Brean pokes a single to centerfield for the game’s first hit. In an all-to-familiar play since the NCAA’s latest imposed aluminum bat standards, Arizona tries to move the runner over by way of bunt, but the batter fouls out after a two-strike attempt. I understand scoring runs against Cole won’t be easy, but Arizona carries the third-best team batting average in the nation and their slugging percentage is good enough to rank 10th. Speedster 2B Bryce Ortega is given the green light to swing the bat and promptly turns on a 0-1 fastball and launches it over the shallow left fielder’s head, and one-hops over the wall for a ground-rule double. Back to the top of the lineup, Joey Rickard weakly grounds out to third base for the second out of the inning, but Mejias-Brean scores on the play. Wildcat 1B Cole Frenzel then golfs a weak liner down the first base line for a double, plating Ortega. Cole gets the ball back and pounds his fist into his glove in frustration. Detractors of Cole, especially when he prepped at Orange Lutheran, would bring up that he was immature or showed signs of frustration that would lead to trouble on the mound. To me, Cole’s reaction to the two runs was merely a sign of his competitive nature that I expected him to channel into a positive focus. Two pitches later and another out via the air (foul-out to 1B) and Cole was out of trouble. Through three innings, Cole has shown good command (no walks and only one three-ball count), five strike outs, only one well-hit ball and is facing a 2-0 deficit. So goes the life of a pitcher, right?

UCLA helps Cole out by scoring three runs in the bottom of the inning due to a string of five hits and one free pass issued by Heyer. Heyer’s fastball hasn’t been missing bats like Cole’s has but his movement is impressive and his fastball has been sitting between 90 and 92-mph.

7:25 PM – Cold War Kids, “Broken Open”

I have been broken open

This was not my master plan

Jason and I spend the third inning chatting with the scouts surrounding us, including two representing the Seattle Mariners (who own the #2 overall selection in this year’s draft and could very well land Cole if Rice University’s Anthony Rendon is taken by the Pittsburgh Pirates with the first pick). Also in attendance are scouts from the Cleveland Indians, Milwaukee Brewers and San Francisco Giants. Sitting two rows behind me with a radar gun and notepad is a gentleman in a University of Vanderbilt visor and windbreaker. Vandy at the time of the game was ranked #1 by Baseball America but after dropping two of three against South Carolina over the weekend, the Commodores currently rank #4. No doubt Vanderbilt is looking towards NCAA Regional play and advance scouting against possible post-season opponents.

The fourth inning was of no interest, unless you are impressed by Cole striking out the side and hitting 98 on the gun twice. One of the Mariner scouts asks the non-uniformed Arizona Wildcat player in front of us who is charting the game if he thinks Cole will touch 100 mph and the teen nods yes and the scout concurs. Unfortunately, Cole wouldn’t hit triple-digits during the game, but it should be noted that he maintained 98-mph velocity in the 7th inning and 96-mph with his 123rd and final pitch of the game.

In the fifth, Mejias-Brean flies out – with only one game to draw conclusions from, it seems to me that Cole will be a fly-ball pitcher as a professional - then Arizona puts together back-to-back singles to bring up Rickard, who promptly deposits a 1-1 fastball over the leftfield fence for a three-run homer. Cole hangs his head for just a second before getting a new ball from the umpire but one can’t fault him on it…had Rickard been using a wood bat, it most likely would have been shattered into pieces but with an aluminum bat, he was able to turn on the ball and fist it 335 feet. The five runs would be all Arizona needed to tag Cole with the loss.

7:42 PM – Interpol, “All of the Ways”

Tell me you're fine

Tell me it's hard to fake it time after time

Who is this guy

Three batters into the sixth and I was convinced that this was going to be Cole’s last inning. A one-out error by his shortstop caused Cole to drop his head and slump his shoulders while he tried to collect himself on the mound. Arizona followed up with yet another weakly hit single, leaving runners at the corners.

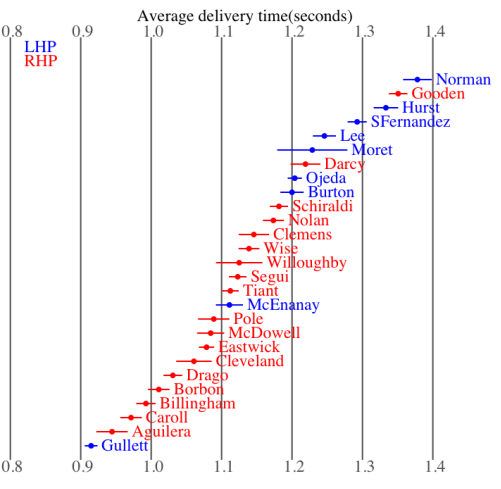

During the earlier part of the game, Cole’s delivery to the plate out of the stretch was a consistent 1.28 seconds but now, at barely 80 pitches, Cole was up to 1.31 and 1.32 seconds to home. His slider was becoming flat and he was increasingly missing his spots. It seemed fatigue (or disappointment) had started to set-in. Then, Arizona decided to lay down a bunt to bring the runner at third home. The bunt rolled toward the left side of the mound and Cole pounced on it and with his momentum taking him towards the plate, he quickly flipped the ball to his catcher, who applied the tag just before the Arizona runner slid into home. “Out!” shouted the umpire and even over the roars of the home crowd, Jason and I could hear Cole grunt “Yeah!” and give his best Tiger Woods upper-cut fist pump.

As quickly as it had disappeared earlier in the inning, energy/adrenalin/confidence returned to Cole and he fanned the next Wildcat batter, the last pitch being a hard changeup that dove away from the batter. As Cole sprinted into the dugout, the scouts talked among themselves about Cole’s recovery during the inning.

7:58 PM – Sleigh Bells, “Rill Rill”

So this is it then?

You’re here to win, friend

One scout returns to his seat after taking a break during the bottom-half of the sixth inning. Instead of holding a radar gun while we watch Cole take the mound in the seventh inning, the grizzled talent evaluator turns his attention to the steaming cup of chili he bought at the snack bar. The smell of the cheese and onions teases my empty stomach so I lean over to the scout and ask, “How would you rate the chili? It smells like a 70.” Without missing a beat, the scout plays along. “Usually it’s an 80 but the weather tonight is too warm, so it’s only a 60.”

Cole’s game is back on track, as he retires the side in order, including a three-pitch strikeout of Frenzel, capped off by a 87-mph back-door slider on the outside corner to freeze Arizona’s #2 hitter.

8:19 PM – Brandon Flowers, “Playing With Fire”

They seem to be leaning

In the wrong direction

First impressions of Cole when I saw him warming up in the bullpen before the game was that this is a big kid with girth in all the right places for a power pitcher: butt, quads and calves. After seeing him repeat his delivery pitch-after-pitch and field his position well, I was fully convinced of Cole’s athleticism. What I saw next left me (and Jason and the scouts and the fans and, most importantly, Robert Refsnyder) off-guard.

With one out in the top of the 8th, Refsnyder laced a single to right field. Throughout the game, Cole kept runners in check with casual tosses to first and flashed a double-move a few times when he was facing runners at the corners. After a few throws that caused Refsnyder to slide headfirst back to the bag, Cole showed a set of quick feet, firing a shin-high bullet to the bag, catching Refsnyder leaning and erasing the runner from the base paths. Cole gave another first pump as the ball was returned. One pitch later - a 96-mph four-seamer resulting in an infield pop-up – and Cole’s night was over.

9:23 PM – Cut Copy, “Hearts on Fire”

There’s something in the air tonight

A feeling that you have that could change your life

During the drive home, I didn’t listen to any music. I replayed most of the night in my head, trying to figure out the negatives I’d need to bring up when breaking down Cole’s performance. As I parked my car, I checked the UCLA website for the night’s boxscore to compare with my game charts. The final stats, along with my scribbled down notes, left me with barely, if any, red flags or weaknesses to assign the UCLA pitcher.

Cole’s final line: 8 innings, 123 pitches, 9 hits, 5 runs (all earned), 0 walks, 11 strikeouts. Of the 33 batters faced, Cole threw 22 first-pitch strikes. He gave up a hard-hit, ground-rule double, a college-bat home run and that was about it. His velocity and movement confirmed what all the scouting reports had said. Physically, Cole looked the part of a top-notch prospect. Sure, it wasn’t his best outing of his young career and it wasn’t a game I’ll tell my grandchildren about ... the chili, on the other hand … but he flashed enough brilliance to show why many expect him to become the top pitching prospect the minute he signs with his new Major League team.

So there you have it, the soundtrack of a prospect. Cole is clearly no one-hit wonder and, based on the hype and performance I witnessed, he’ll be music to a team’s ear come June.

| Designated Hitter | March 01, 2011 |

I am not now, nor have I ever been, a collector of autographs, baseballs, baseball cards, etc. As a kid in the '50s, I'd buy baseball cards to look at, memorize the stats on the back and to flip them (heads or tails, against the wall, anything we could think of). The following spring, I'd throw out last year's cards and start again. The most fun about getting autographs was you got to be next to the player to ask for it. That was thrill enough for me. It never crossed my mind that people in the future would make money from collectibles.

I was a Pirate fan living in New York City during the '60s. There weren't many of us. Roberto Clemente was my guy. In the same way that Mickey Mantle or Willie Mays or Sandy Koufax were your guys if you were a Yankee, Giant or Dodger fan. I loved him, wanted to play like him and tried to emulate him on the field. And I wanted his autograph. I can tell you literally dozens of great Clemente stories that I was around for during this era. Here's one of my favorites.

Getting Clemente's autograph was not the easiest thing in the world. He went through his baseball life with a chip on his shoulder. Not that he wasn't justified. With the exception of Jackie Robinson, I doubt any ballplayer was treated as badly by the press as Clemente was and he took every slight personally. He was black, Latino and spoke not one word of English when he came here in 1954 at the age of 19. Sportswriters, perhaps just not used to dealing with Latino players, would quote him phonetically, which made him look bad. "I theenk I have goood seeson." Learning to speak English was not easy for him.

You had to ask for his autograph when he was in a good frame of mind. Me and my buds would go down to the hotels where the teams were staying when they were in town to play the Yankees or Mets. Most teams stayed at the Hotel Roosevelt, the Pirates at the Hotel Commodore. We'd get there on Saturday mornings just before the bus would take them to the Bronx or to Shea and ask for their autographs in the lobby. Most would sign, some wouldn't.

I first got Clemente's autograph on August 18, 1964, which I knew was his 30th birthday. I was rowing boats six days a week all summer as a dock boy at Brooklyn Day Camp. I called in sick that day and went to Shea for an afternoon Pirate/Met game. Back then, I used to write to the Pirates for glossy photos of the players and they'd always oblige. So I had a few pages of Forbes Field stationery with me.

After the game, I waited outside the clubhouse for the Pirates to board their bus. Clemente comes out and a bunch of kids swarm around him. "Can I have your autograph, Roberto?" For whatever reason, he wasn't signing that day. Frank Oceak, the Pirates 3rd base coach, sees me holding my pen and paper and tells me, "Talk to him in Spanish and he'll sign for you." The proverbial light bulb goes on over my head! I took three years of torturous Spanish classes with Mr. Capitano in Junior High School!! "Roberto, Feliz Cumpleanos," I say. He puts down his suitcases, smiles and signs his name on my Forbes Field paper. I kept telling myself that Roberto Clemente likes me. A great moment.

Many decades later, the autograph on that paper is worth quite a bit. Supply and demand. Clemente didn't sign that many and died at age 38. Pete Rose has made his living by signing his name for the past 22 years. I took my Clemente autograph to a card show one time and showed it to a dealer, who immediately offered me $500 for it. Which told me it was worth much more than that. It is not for sale.

For the past 30 years, David Bromberg has lived in Northeast Pennsylvania, former home of the Scranton/Wilkes Barre Red Barons (Phils Triple A team) and current home of the S/WB Yankees Triple A team. He was dubbed "the most inveterate baseball fan in northeast Pa. by Ron Allen, who hosted the local nightly sports radio call-in show there.

| Designated Hitter | February 13, 2011 |

Woodie Fryman died last week at the age of 70. He was as average a pitcher as you can be. 141-155 during an 18 year career. He used a double-pump windup, which you didn't see very much of anymore when he broke into the majors in 1966. He was 12-9 that year with a 3.81 ERA — not bad for a rookie. Until you consider that Forbes Field was a huge pitcher's park, this was during the enormous strike zone era, and he pitched three consecutive shutouts in a two-week stretch. The rest of his season was absolutely average. The one thing that stands out is that he threw four one-hitters. I was at the first of them.

I was a rabid Pirate fan living just a few miles from Shea Stadium. July, 1966 and Fryman is pitching a Friday night game at Shea. One aside. The 1966 Pirates will forever be my favorite team. Matty Alou won the batting title, Willie Stargell had his first big power year, and shortstop Gene Alley and second baseman Bill Mazeroski helped set the all-time record for double plays in a season. And then there was Roberto Clemente. He won the National League Most Valuable Player award that year. If your only memory of Roberto is the 1971 World Series, picture him dominating games like that for an entire season. He was something to see. The Pirates were thrilling to watch and I almost never missed a game when they came to town.

Pittsburgh led the NL for most of that season, eventually finishing third to the Dodgers and Giants, three games out of first place. Whenever they team played in San Francisco or Los Angeles, I'd stay up very late listening to the games, trying to get Bob Prince coming in above the static calling the games on WWVA radio, out of Wheeling, West Virginia. The crime of that season was the Dodgers had Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale, the Giants had Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry, and we had only Bob Veale and Al McBean!! You call that fair???

Back to Fryman's gem. Ron Hunt leads off the game for the Mets. Chops a ball over Woodie's head. Gene Alley, at short, charges it and tries to one-hand it and throw to first, but the truth is not even Ozzie Smith or Omar Vizquel could've made that play. Infield single. Hunt gets thrown out trying to steal second base and then 26 up and 26 down. A one-hit shutout. Faced only 27 batters. No incredible fielding plays, just 26 up and 26 down. Easily the best pitched game I've ever seen in person. Stargell hit two home runs and the Pirates won 12-0.

After the game, Pirates manager Harry Walker insisted on speaking to Dick Young of the Daily News, the official scorer that night. These were two rather hot-headed guys. Walker wanted Young to change the infield hit to an error, so at least Fryman could have his no-hitter. The whole thing escalates, pushing, shoving and cursing. Walker was suspended for one game and Young wrote articles for days afterward about what a jerk Harry Walker was.

By the time the Pirates became an NL power (five NL East titles between (1970-75), Woodie Fryman was long gone. But I'll never forget that night 45 years ago.

David Bromberg has been going to baseball games since 1955. He was at Yankee Stadium two days before Don Larsen's perfect game in 1956 and at Shea Stadium two days before Jim Bunning's perfect game in 1964. He's never attended a no-hit game.

| Designated Hitter | August 17, 2010 |

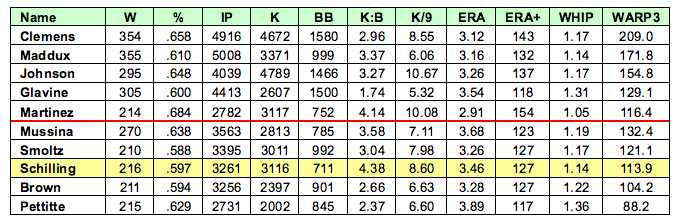

In my last article, I examined at what ages the forty greatest hitters* of all time, as measured by Wins Above Replacement (“WAR”), had their five best seasons to learn about aging patterns and how certain individual players fared. Here, I take a look at forty top pitchers and their best seasons. Because pitcher usage has changed dramatically over time, I eliminated all pitchers who played the bulk of their careers before World War II.

I don’t think that Walter Johnson’s typical workload of 350+ innings in his best seasons or Cy Young’s 400+ innings in his best seasons is particularly enlightening for purposes of today’s game because modern players are unlikely ever to pitch like that again. That is to say nothing of Old Hoss Radbourne’s 19.8 WAR season in 1884, in which he pitched 678 innings and went 59-12. (Considering his ERA-plus was 207 that year, and he pitched about 2/3 of his team’s innings, I think his WAR (he had 20.3 when you factor in hitting), although the highest single season number of all time, seems a bit low). In any event, after taking out the old-time pitchers, the top-40 post-World War II pitchers takes you down to number 67 of all time, Dave Stieb.

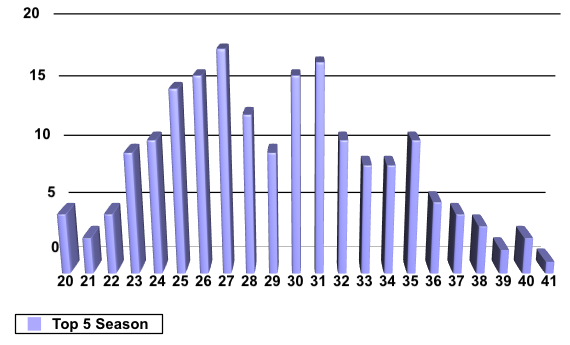

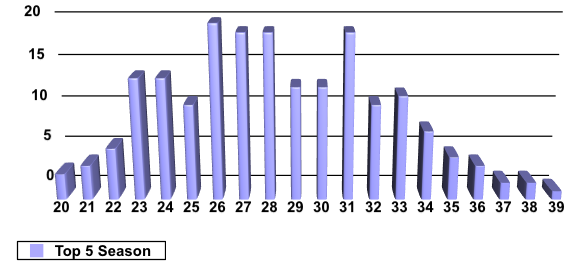

I plotted on the bar graph below the top 5 pitching seasons measured by WAR (I did not factor in WAR for hitting) for the 40 top-rated post-war pitchers (200 data points in all). For comparison sake, I have also included the chart for hitters from my last article, adjusted so that the pitchers and hitters are set out in the same scale.

Top 40 WAR (Post-World War II) Pitchers:

Top 40 WAR Hitters:

The Pitchers vs. the Hitters

The first thing that jumps out from looking at these graphs is that pitchers seem to spread out their peak seasons far more than hitters. Although great hitters and pitchers start putting up peak seasons at age 20, the pitchers are far more likely to have a peak performance late in their careers. Just three hitters had one of their best seasons at age 38 or later (one was Barry Bonds at 39, one was Ted Williams who had his fifth best season and one was Cap Anson), and none at age 40, whereas the pitchers had 10 such seasons starting at 38 (5% of the sample) and four at 40 or 41, by which time all great hitters had tailed off. Similarly, the peak for pitchers is far less prominent than for hitters. For the hitters, 103 of the best seasons, more than half the sample, were between ages 26 and 31. For the pitchers, by contrast, at the same ages (which is also the six year span with the highest number of peak years) there are just 88 of the 200 seasons recorded. The median age for a pitcher’s top season was 29, a year later than for the hitters. Another interesting observation is that aggregately both the hitters (at 29 and 30) and pitchers (at 28 and 29) showed a decrease in peak years before spiking again. In my last article, I had chalked up this anomaly as merely a sample size issue, but now I wonder if there is something more at play. Perhaps players need an adjustment period to cope with diminishing physical skills.

The Individual Performances

One of the things that makes an exercise like this interesting is to look at the individuals who make up the sample and examine some of their performances. On the old side, it is not shocking that Phil Niekro and Ryan put up great age 40 seasons. John Smoltz, had the other age 40 season on the chart, which I found surprising. Warren Spahn’s age 41 season ends the chart. (Incidentally, at a baseball card show when I was 13, Spahn taught me how to throw a knuckleball. He claimed he threw one once in his career, popping up Ted Kluszewski. He also recounted how kids at Ebbets field threw sandwiches at the visiting pitchers in the bullpen, and he and his teammates would collect them and, occasionally, eat them).

Smoltz, for his part, was the pitcher with the biggest range among his top 5 seasons, producing them from ages 24 to 40. Other pitchers with a greater than ten year span for their best five seasons include Roger Clemens (23-34), Spahn (26-41), Bert Blyleven (20-33), Nolan Ryan (26-40), Steve Carlton (24-37), Mike Mussina (23-34), Rick Reuschel (24-36) (one of the most surprising things I saw was that Reuschel has the 30th highest WAR for pitchers all time, ensconced between Tom Glavine and Bob Feller, two no-doubt Hall of Famers (or future Hall of Famers)), Jim Bunning (25-35), Tommy John (25-36), Jerry Koosman (25-36), David Cone (25-36), Chuck Finley (26-37) and Frank Tanana (20-30).

On the young side of the spectrum, the eight age 20-21 seasons on the chart belong to six pitchers, Blyleven, Feller, Don Drysdale, Dennis Eckersley, Tanana and Bret Saberhagen. Blyleven, 13th all time in pitchers’ WAR (making it very hard to deny his Hall of Fame credentials, but Rich speaks far more eloquently on that subject than I do), turned in four of his top-5 season at 20, 22, 23 and 24 (with his fourth best season at 33). Perhaps his underwhelming won-lost records for those early years (16-15, 20-17, 17-17, 15-10, respectively), coupled with a long career thereafter of being very good has caused him to be underrated in the popular (sportswriters’?)

consciousness.

Feller, another young peak performer, suffers no such lack of recognition among baseball’s cognoscenti, and for good reason. Rapid Robert’s best five seasons were at 20, 21, 22, 27 and 28. Of course, he missed all of his age 23-25 seasons, and most of his age 26 season, to World War II, creating an equally compelling “what might have been” discussion as the one for Ted Williams. Another “what might have been” could easily be created for Frank Tanana, who put up four of his top 5 seasons between 20 and 23, including three 7+ WAR seasons from 21-23. To put that in perspective, among the last ten Cy Young award winners (Lincecum twice, Peavy, Webb, Carpenter, Grienke, Lee, Santana, Sabathia, and Colon) they have just four 7+ WAR seasons aggregately in their careers (Grienke, Lee and Santana twice). Had Tanana not blown out his arm, he may have been among the all time greats. That he was able to reinvent himself into an effective junk-baller is a credit to him.

On the other end of the spectrum, late peaking pitchers include knuckleballer Phil Niekro (his top five were between age 35 and 40), fireballer Randy Johnson (31, 33, 35, 37 and 38), spitballer Gaylord Perry (between 30 and 35) and sinker baller Kevin Brown (31-35). Smoltz had three of his best seasons at 38-40, but his other two top seasons were at 24 and 29.

Brown was also one of the models of consistency with a definitive peak, putting up his best five seasons in a row. Robin Roberts (23-27) was also on that list. Greg Maddux (26-31), Sandy Koufax (25-30) and Hal Newhouser (23-28) each put up their best six seasons in a row.

Conclusion

When viewed aggregately, pitchers, like hitters, apparently age in predictable ways, with peak years likely to take place between 26 and 31. On deeper inspection, however, it is clear that pitchers are less predictable. A 37 or 38 year old pitcher, or even older, has a reasonable possibility of turning in a personal peak year, whereas a hitter is not likely to do so. Indeed, each of the five oldest peak years for hitters have extenuating circumstances (Bonds (37 and 39) because of presumed steroid use, Williams (38) because service in World War II almost certainly cost him a top season when he was younger, and Cap Anson (37 and 38) because he played in the equivalent of baseball’s pre-historic times, where talent was almost certainly not as uniformly recognized and spread out among the leagues. If those players’ late career seasons are discounted, no top hitter would have had a peak season after 36. By contrast, the top 40 post-war pitchers put up 15 (7.5%) of their top seasons at 37 or older. Nor is it clear that a single type of pitcher is destined for late-career success, as pitchers such as Phil Niekro, Spahn, Randy Johnson, Carlton, Ryan, Smoltz, Koosman, Cone, John, Finley and Reuschel each put up one of their best five seasons at 36 or older.

If anything, the late success of pitchers seems to show what baseball fans already understand, that pitching effectiveness is not the result of merely being able to throw hard (no doubt each of these pitchers could throw harder when they were younger). Rather, factors such as an improved or learned pitch, better control, or even better discipline and thought processes on the mound no doubt contributed to many pitchers’ late career resurgences. Another conclusion that should be apparent is that next year’s prized free agent, Cliff Lee, who will be entering his age 32 season, is not nearly as assured of regressing from his incredible current peak as a 32 year-old hitter would be. No doubt, many GM’s are willing to bet that he can produce excellent seasons in his mid-30’s, just as some

great pitchers have done before.

* Note that I intentionally omitted Albert Pujols from that analysis, as it is by no means clear that he may not still have one of his five best seasons in the remainder of his career. In posting that article, the footnote on that subject apparently became embedded.

Doug Baumstein is an attorney and Mets fan living in New York.

| Designated Hitter | July 30, 2010 |

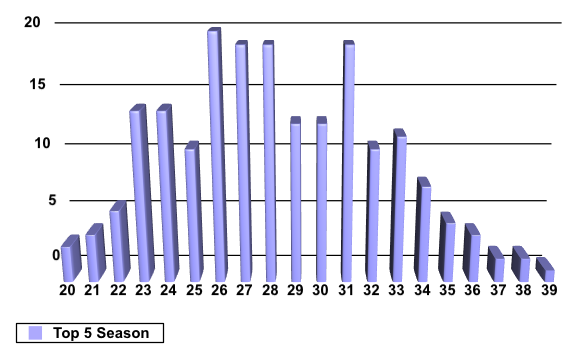

In this article I examine at what ages baseball’s very best hitters had their best seasons as measured by wins above replacement (“WAR”). I looked at the top 40 position players in career WAR and plotted their top 5 seasons against their age during that season. Thus, with 200 data points in all, I created the below chart plotting a player’s personal top 5 season against his age.

Obviously, looking just at the numbers is not that enlightening, so I also noted some of the more interesting results as they pertain to individual players. For example, the three 20-year old seasons that were among the personal top 5’s of the players on the list belonged to Mel Ott, Al Kaline, and Alex Rodriguez. I, for one, would not have guessed that one of A-Rod’s best seasons was his first complete season. The four 21-year old seasons that make the list belong to Rickey Henderson, Eddie Matthews, Jimmie Foxx and Ken Griffey Jr.

On the other end of the spectrum, the 39 year-old season belongs to Barry Bonds, who likely found his fountain of youth in a syringe. The two age 38 seasons on the list almost certainly had nothing to do with chemical enhancement, as they belong to Cap Anson and Ted Williams. Anson, as it turns out, was not only a great old-time player (even if less than a great human being), but was one of the greatest old players, turning in his best five seasons at 29, 34, 36, 37 and 38. Williams, for his part, of the top 40 hitters, had the biggest age gap among his top 5 seasons, turning in one at 38 and one at 23. That, however, is likely more a function of geopolitics than playing ability, as Williams turned in an 11.0 and 11.3 WAR season at the age of 23 and 22 in 1942 and 1941 and an 11.8 and 10.3 WAR season during his age 27 and 28 seasons in 1946 and 1947. Although, had he played and not fought in World War II there is no guarantee he would have exceeded the 9.9 WAR season he had at 38 years-old (10 WAR seasons are few and far between), had he had one such season during the three years between 1943 and 1945, the 15 year difference among his top 5 seasons would not have existed. Other top players who turned in at least two of their top 5 seasons more than ten years apart include Barry Bonds (age 28 to 39), Tris Speaker (24-35), Al Kaline (20-32), Carl Yastrzemski (23-33), Joe DiMaggio (22-33), Rickey Henderson (21-31), A-Rod (20-31), Eddie Matthews (21-31) and Chipper Jones (24-36).

A number of players put together their 5 best seasons in a row, showing a true peak and incredible consistency. Those players include Hank Aaron (25-29) (I always thought of him as someone who had his best years late, but he actually peaked on the young side), Honus Wagner (31-35) (a renowned older superstar), Joe Morgan (28-32), Wade Boggs (27-31) (I would not have guessed that he was a top 40 WAR hitter, and he was actually number 27, ahead of George Brett (number 30) who I consider the better player), Charlie Gehringer (30-34) and Rod Carew (27-31). A few others put up their best 5 seasons in a six year span, including Roger Connor (27-32), Roberto Clemente (31-36) and Jeff Bagwell (26-31). I find Clemente’s late surge especially interesting. I have always believed that, to the casual fan, Clemente was one of the most overrated players ever. He died after his age 37 season, shortly after the most productive stretch of his career, possibly increasing the halo effect surrounding his untimely and tragic death, and potentially creating a stronger impression of his playing abilities than might otherwise have been deserved had he gone through a typical decline phase.

I also looked at some players outside of the top 40 to see if there were any interesting patterns. Craig Biggio showed a consistent peak, turning in his top 6 WAR years from 28-33. Jim Edmonds showed a late peak, turning in his top five years from 31-35. Paul Molitor’s top five seasons also showed a late peak at the ages of 34, 35 and 36, although his age 25 and 30 seasons also constitute his top 5.

Conclusion

When I started this exercise (and I did look at a lot more stars from the so-called steroid era, even if they were not in the top 40), I expected to see that modern stars, as a result of advances in training, exercise, medicine and performance enhancing drugs would turn in the best “old” seasons. Other than Barry Bonds’ anomalous age 39 season, the evidence seemed to point the other way, as players such as Honus Wagner, Cap Anson and Roberto Clemente all showed later peaks than typical current-day star players. Also, I was surprised that 7 (or roughly one in six) of the superstars who I looked at turned in one of their top 5 seasons at age 20 or 21. While it is not surprising that superstars break in early, it is surprising that many had among their best seasons before they legally could buy a beer in today’s world (although Jimmy Foxx didn’t seem to have a problem in procuring a beer in his time).

I also performed a quick review of post-World War II pitchers. Although I did not find anything all that surprising, pitchers seemed to show a far greater dispersal in value at different ages. Time permitting, I will take a look at that data and prepare a similar study, and see if pitchers age differently than hitters or whether their peak seasons generally occur during their late 20’s.

Doug Baumstein is an attorney and Mets fan living in New York.

| Designated Hitter | June 01, 2010 |

One of the great insights of the sabermetric revolution is the recognition that when evaluating a player, context counts. Ballparks, scoring environments, teammates, leagues and a host of other factors often give the illusion of success (or failure) to a ballplayer’s career. In this article, I take a look at some players through the prism of their road statistics to try to tease out differences in performance and ability that may cause you to think differently about certain stars of the last 50 years.

Intuitively, we recognize that hitters who play in great environments like Coors are benefitted and that players in cavernous stadiums are generally hurt. I am not sure, however, that we ever truly appreciate that some players, as a result of hitting style, luck or other reasons, are inordinately benefitted or hindered by their home ballpark.

By looking at just a player’s career road statistics, I try to separate out the effect of a player’s home ballpark and come to some interesting observations when certain hitters are compared “all else being equal.” The theory is simple, by examining a player’s away statistics, we get to view a player’s production playing at what is close to a league-average neutral park because all the park’s except the player’s home stadium are counted. The methodology is also equally simple, for purposes of this article, I will lay out a player’s slash statistics (avg./obp./slg.) and double his home runs, hits, RBIs and runs accumulated on the road so that the totals replicate traditional career numbers. Obviously, players play very similar amounts of games on the road and at home, so doubling does not reflect differences in opportunity and, by focusing on career statistics, sample size problems are easily avoided. Also, the players I compare here (usually with a player A and player B format) were contemporaries, so they may be playing in the same ballparks at the same time (although league differences may skew the results a bit). Nevertheless, the “road career” I have created here often differs markedly from the numbers we associate with a lot of the great players discussed.

From looking at a lot of home and road splits, I made a number of observations I will pass on. For a host of reasons, some of which we can guess about, over the course of their career, players generally perform better at home than on the road. Additionally, players probably deserve some credit for learning to take advantage of their home ballparks (or were recognized by talent evaluators for having skills that would translate well to a particular ballpark), so taking away their home stats probably over-penalizes a player a bit. Finally, it is clear that two venerable ballparks, Fenway and Wrigley, result in giant advantages for certain hitters. So I suspect that a number of Red Sox and Cubs fans will have particular views about this article. All the players discussed below had complete careers after the retro sheet era, so there are not gaps in their numbers. Without further ado, here are some comparisons for discussion:

Example 1 – The Hall Of Very Good

For my first example, I am comparing two players whose careers largely overlapped in the National League. Both were multiple gold glove fielders playing the same position in the middle of the defensive spectrum. Both played in lower run scoring environments than today. Both are in the Hall of Merit, but only one is a cause celebre as an unjust Hall of Fame snub.

Player A won 5 gold gloves, was an eleven time all star and won one MVP. He performed better at home and his slash line away is .277/.340/.443. If he spent his career on the road, he would have accumulated 2066 hits, 268 homers, 996 RBIs and 1056 runs.

Player B also won 5 gold gloves (starting right after the run of Player A) and was a nine time all star. His highest MVP performance was fourth. He too performed better at home, and his slash line away is .257/.342./406. His “career on the road” yields 2092 hits, 256 homers, 1176 RBIs and 958 runs.

Both players are pretty even, but seeing the above, I would take Player A. If you haven’t guessed, Player A is Ken Boyer, Player B is Ron Santo. Santo mashed at Wrigley over his career (.296/.383/.522), but was just ordinary on the road. Take away the Wrigley advantage, and these guys were about as even as they come in playing ability. (The comparison above is not entirely fair, because, even though their careers overlapped, Santo peaked in the ultra-low scoring environment of the late 60’s, by which team Boyer’s career was basically over.) Nevertheless, the numbers cause me to question whether Santo really is as deserving for the Hall of Fame as many now believe (and frankly, I did before looking at his splits).

Example 2: The Best Right Handed Hitter of the Steroids Era?

The next four players were all born within a few months of each other in 1968 (two share a birthday, which already will alert some trivia buffs). These right handed sluggers debuted between 1988 and 1992. Who was the best?

Player A has a .297/.414/.511 slash line on the road. His career on the road yields 2444 hits, 418 dingers, 1630 RBIs and 1368 runs. He is a 5 time all star and two time MVP. With the glove, he is best remembered as a hitter.

Player B has a .288/.384./.501 slash line on the road, and would have had 2704 hits, 1594 runs, 494 homers, and 1670 RBIs had his entire career been played on the road. He was a nine time all star and his best showing for MVP was second. Although not a good fielder, he was versatile, having played all over the diamond during his career. He is also generally regarded as one of the surlier stars of the past twenty years.

Player C has a .291/.398/.521 away slash line, with 2306 hits, 1422 runs, 430 home runs, and an even 1500 RBIs. He was a four time all star, one time MVP and garnered one gold glove (and was generally regarded as a good fielder).

Player D has a .320/.388/.572 slash line. This road warrior’s away career would have garnered 2328 hits, 1094 runs, 464 homers and 1414 RBIs. He was a twelve time all star and his best showing for MVP was a couple of second places. Oh, did I mention he was a catcher?

If you haven’t guessed, the above are, in order, Frank Thomas, Gary Sheffield, Jeff Bagwell and Mike Piazza. Piazza’s power and overall hitting on the road is astounding, as he gets an additional 20 to 30 points in average over the other greats here and sports a slugging percentage fully 50, 60 and 70 points better than Bagwell, Thomas and Sheffield, respectively. Piazza had the unlucky circumstance of having played most of his career in Chavez Ravine and Shea, two parks that are tough on right handed power hitters. Even his short stopovers in Oakland, San Diego, and a week of games for the Marlins were all played in pitchers’ parks. He is one of the small percentage of players whose road numbers are better than his home numbers (.294/.364/.515). He averaged 38 homers per 162 games on the road. A good argument can be made that Piazza was the best right-handed hitter of this bunch. I don’t know that many would have argued that before seeing the numbers. Rather, I imagine most people would think Frank Thomas was the best hitter of this group. Thomas, for his part, had 100 more home runs at home than on the road, showing he may have benefitted inordinately from favorable home parks well suited for his hitting. His career home numbers, primarily at Comiskey, are a phenomenal .305/.424/.599.

As a side note, Manny Ramirez, who is four years younger than this group, has even more impressive away numbers (as well as a much closer association with the “steroids era” than Thomas, Bagwell and Piazza). At the time of this writing, his road slash numbers are .313/.408/.582, even better than Piazza’s, and he has produced comparable line, .313/.414/.596, at home.

Example 3: a Trio of 3000-Hit Slap Hitters

When I think of great career hitters for average, three names that jump to mind are Tony Gwynn, Wade Boggs and Rod Carew. Among the three, they all finished with between 3010 and 3143 hits, all hit between .328 and .338, with on base percentages between .388 and .415 while slugging between .429 and .459. Below are three slash lines, and the number of hits they would have if they played all their games on the road.

Player A: 3088 hits, .323/.385/.425

Player B: 3172 hits, .334/.384/.451

Player C: 2774 hits, .302/.387/.395

In order, that is Carew, Gwynn, and Boggs. Carew and Gwynn, on the road, hit like Rod Carew and Tony Gwynn. Wade Boggs hits like Al Oliver (career 2743 hits, .303/.344/.451).

Boggs is not the only 3000 hit-club member who received a big boost from Fenway. One of the most notable “road careers” is that of Carl Yastrzemski, who put up a career .264/.357/.422 on the road, with what would have been 3194 hits, 430 homers, 1644 runs and 1562 RBIs. Not a lot of .264 hitters get to 3000 hits, so it is hard to believe that Yaz could have gotten there without the benefit of a home park that suited him well and helped keep him in the lineup for 23 years. His career line at home is an impressive .306/.402/.503.

Example 4: Let Wrigley Double Your Pleasure

Now let’s take a look at three Cub icons, Ryne Sandberg, Billy Williams and Mr. Cub himself, Ernie Banks. I have compared the first two to long-time Tigers Lou Whitaker and Al Kaline (the number one and three most comparable players to each, respectively, according to Baseball Reference) and Banks to his top comparable, Eddie Mathews. Only one of the long-time Cubs’ road numbers hold up, can you guess who?

So here are the second sackers:

Player A: With a .269/.326/.412 line, this second baseman’s road career yields 2256 hits, 1184 runs, 908 RBI and 236 homers.

Player B: With a .274/.357/.406 line, this second baseman would have tallied 2394 hits, 1310 runs, 1070 RBIs and 196 homers with a career entirely on the road.

And the outfielders:

Player A: With a .278/.349/.459 line, this outfielder’s life on the road would garner 362 homers, 2596 hits, 1363 RBIs and 1298 runs.

Player B: With a .292/.369/.458 line, this outfielder would clout 346 homers, with 1510 RBIs, 1568 runs, and 2998 hits if his career took place solely on the road. I am pretty sure he would not have found a way to get a couple more hits.

And the slugging infielders:

Player A: His .259/.311/.462 on the road would result in 444 homers, 2424 hits, 1454 RBIs, 1168 runs and an inordinate number of outs.

Player B: His .277/.382/.529 line would result in 548 homers, 2468 hits, 1574 RBIs, 1624 runs and likely consideration as a member of the inner circle of Hall of Famers.

In all the examples above, the Cub is always Player A. Take Ryne Sandberg out of Wrigley, and he doesn’t look like a Hall of Famer, even for a second baseman. Of course, his .300/.361/.491 career line at Wrigley counts toward his bottom line, so he skated in to Cooperstown. In this exercise, however, Whitaker’s career looks more impressive than Sandberg’s when you factor in the longer effectiveness as well as the additional 30 points in on base percentage. That Whitaker couldn’t even manage to stay on the Hall of Fame ballot is a travesty.

Williams holds up remarkably well (and better than I would have thought), considering he wasn’t quite the hitter Kaline was when factoring in home numbers. Williams’ home slash stats of .302/.374/.525 are still much better than his road numbers, however.

The Mathews/Banks comparison is especially revealing, as Banks and Mathews played in the same league at the same time. Mathews simply laps Banks. Mathews was better on the road than at home (.264/370/.488) over the course of his career. Hank Aaron, Mathews’ right-handed power-hitting teammate, produced virtually identical numbers home and away, so it is not self-evident that the Braves’ ballparks were a burden on right-handed power hitters. (Willie Mays, like Aaron, also produced virtually identical numbers at home and on the road, refuting the oft-repeated, and oft-debunked, myth that his power numbers were sapped by unfortunate home venues.) Banks was a different, and better, hitter at home, where he had a career line of .290/.348/.537, a more than .110 point difference in OPS. Considering he played fewer than half his games at shortstop, had Banks spent his “career on the road,” so to speak, it is not clear he would have been a Hall of Famer, and certainly would not have been thought of as an elite member of the Hall, as he generally is now.

Conclusion

I suspect a lot of people will argue that this methodology is unnecessary because OPS plus factors in home ball parks or that a player should receive full credit for taking advantage of his environment. I think, however, that looking at only road statistics serves as a great equalizer in assessing such questions as, “who was better?” When we ask that question, we generally don’t mean to look merely at accumulated statistics without context, but to examine the question in light of a platonic ideal of a great hitter. A great hitter is a great hitter at home, on the road or in the middle of a cornfield. Hits, and especially home runs, are often the result of hitting a ball well in a stadium that rewards it, and not all players end up in parks that reward their skills. Simply, ballparks do not behave equally or match a hitter’s strengths equally. By looking at the amalgamated statistics of a player on the road, I believe we gain better insight into a player’s performance by eliminating the home field advantages or disadvantages that a player faces in half his at bats.

Finally, for some parting thoughts, here are some other observations I made. For example, I always considered Kirby Puckett and Don Mattingly interesting comparables in terms of Hall of Fame debates. Puckett hit just .291/.330/.431 on the road compared to .302/.353/.450 for Mattingly. In my mind, neither cuts it as a Hall of Famer based on their short careers. If I ever thought there was an offensive difference between Dave Winfield (.289/.356/.485) and Eddie Murray (.286/.356/.482) I certainly can’t believe there is one now. I find it hard to make a strong case for Jim Rice as a Hall of Famer based on his weak road stats (.277/.330/.459), especially when Edgar Martinez (.312/.412/.514) is such a long shot. I have a heightened appreciation of Jeff Kent (.290/.353/.504) who toiled for several teams, mostly in pitchers’ parks. The magnitude of difference between Larry Walker on the road (.278/.370/.495) and at home (.348/.431/.637), while predictable, is nevertheless astounding.

Often, a review of splits confirms our perception of a player, but in some cases, it challenges it. While not the ending point of all debates, looking at road statistics provides new and often unexpected insights.

Doug Baumstein is an attorney in New York and Mets fan.

| Designated Hitter | May 29, 2010 |

The near perfect website called Baseball Reference rents out the heading sections of its player-pages to help support its unequalled statistical product. Unique to this kind of sponsorship is that the Reference auctions off access to the headings, creating a kind of fan marketplace, with better players yielding higher prices than lesser players. This means the player pages of legends like Ted Williams and Willie Mays are nabbed by blogs or memorabilia companies eager to piggy-back on more visible pages. Yet the lesser, and more importantly cheaper, player-pages typically have far more clever text; usually some blend of sarcasm and nostalgia created by someone very bored and devoid of real commitments, someone like myself.

One of my favorites of this type headlines Giants great Johnnie LeMaster’s page. Submitted by David Rubio, it reads “Underachievers have always had a place in my heart. Johnnie was a favorite of mine.” The LeMaster line led me searching for more. I thought another Giants shortstop would be a natural target for someone with the right love of the esoteric and immature, Jose Uribe. Unfortunately no one had bothered to sponsor poor Jose. But the drifting got me thinking about a question: who is the greatest shortstop to ever play for the San Francisco Giants? My instinct was to dismiss recent players outright, I had watched every shortstop since the mid-80s and not one of them had found a place in my heart. I also knew little about the 6-hole guys who played for the early teams so my curiosity and presumptions led me to the beginning, 1958.