| Designated Hitter | January 31, 2008 |

[Editor's note: Russ McQueen and my brother Tom were All-CIF pitchers on the Lakewood High School team that won the California Interscholastic Federation championship at Anaheim Stadium in 1970. Russ played on four consecutive NCAA championship teams at USC. He was named the College World Series MVP in 1972 when he pitched 14 shutout innings in relief while chalking up three of USC's five wins and saving a fourth. A 1970s CWS All-Decade selection, McQueen tossed a no-hitter vs. Cal to mark the opening of Dedeaux Field on 3/30/74. Russ was drafted by the California Angels in June 1974 and pitched three years in the club's minor league system.]

As I recently read some of Rich's articles, I was taken back to the Lakewood High baseball field one dreary, overcast, fall Saturday morning.

Seated in the third base dugout, I tried to stay as close to manager, scout and former Dodger pitcher Ed Roebuck as possible, to catch whatever he might say to help me comprehend the game of baseball. He might even ask me to get loose and pitch an inning or two; that is, if he ran out of pitchers or happened to remember I had thrown batting practice the last several Saturdays.

There was nothing unusual about seeing new faces, arms and bats at "The Lake" on a Saturday morning. After all, it was a scout league where minor leaguers and some college guys would show up for some work. A few of us high school guys came out in case... well, just in case.

A new fellow came by that morning with a big equipment bag and exchanged quick hellos and howaryas up and down the line. He meant nothing to me, and I figured him for another lower minor leaguer looking for some work. Mr. Roebuck caught his eye and offered, "Get loose and work a couple innings if you want to."

"If you want to?"

I thought no more about it, other than to spend an inning or so quietly lamenting the fact that I'd now have to wait at least two more innings to have any hope of hearing those words myself.

Then something happened.

The new guy took the mound and things changed. An air of expectancy took hold, and the place got quiet. Sounds were reduced only to those necessary. It felt like a premonition of something terrible, or terribly great, like right before a big fish takes your lure and you know in your gut he's about to hit.

The first batter took his stance. Fast ball, strike one called. Not bad, right down at the knees and on the inside corner. With considerable zip. Not the one he wanted to hit, I thought. But then the new guy threw something I had never seen before. It was gorgeous, and it was terrible, and I wasn't sure I had seen it correctly. Fast like a heater, but in front of the plate it made a wicked dive, down and a little bit away from the batter, who buckled at the knees. Strike two called. Hearts beat faster – I know mine did.

"Throw it again," I prayed.

He did, only this time the batter mustered up a feeble excuse for a swing and made his retreat back to the bench, where he joined other mortals to watch the continuing carnage.

Five more up, five more down. One guy grounded out, but everyone else fell to that monstrous, terrifying curve ball.

I've seen the Grand Canyon and the Grand Tetons. I've walked into Yankee Stadium and Fenway Park and Wrigley Field on a Sunday afternoon. I've been to dozens of countries all over the world and seen it all. But I have never seen anything more riveting than that curve ball on that one cool, gray Saturday morning.

I have always remembered that awesome pitch as a big hammer the new guy swung and pounded batters with. It certainly went way beyond any fair deal I ever witnessed. To say "he threw a curve" was to understate the terror of the act. However ordinary the new guy looked to begin with, to me he had become substantially taller, heavier, and more dangerous.

For a moment there was no one sitting between me and Mr. Roebuck. "That's some kind of a curve ball," I managed, trying to make it sound as casual as I could so Mr. Roebuck wouldn't think I was overly impressed.

"Son, that's a pure yellow hammer," replied Roebuck. "And that is Bert Blyleven."

Russ McQueen, a CPA with PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, is married to his wife Betty (thirty-two years) and has three sons, including Matt, first baseman for the Biola University Eagles.

| Change-Up | January 30, 2008 |

During their recent back-and-forth, in one of Buster Olney's responses to Rich Lederer, he boiled their differences on Jim Rice down thusly:

Many analysts don't think Rice walked enough and believe RBI is a junk stat and that Rice had no other skills other than amassing hits. Rice supporters like myself place a higher value in hits and RBI, especially given the context of the time. So be it.

Leave aside the tone of the statement, and even leave aside the oversimplification. Olney's willingness simply to count up hits and RBI with an apparent disregard for defense, baserunning or most importantly, out-making is what stands out. It's this final item, out-making, that this piece will endeavor to bring into more clarity.

Articulating the value of an out would be redundant. It's been written or said artfully already by many in and around baseball. Below are some excerpts that help lay it out as plain as day.

The currency of baseball is the out. There are a finite number of outs that a team can make in one game, and it is almost always 27 (or 3 outs/inning * 9 innings/game). A player consumes these outs to create runs, and at the simplest level, runs and outs are the only truly meaningful stats in baseball.

He always said, ‘you only get 27 outs in a game, so don't waste them...'

The higher a player’s OBP, the less often he’s costing his team an out at the plate. Viewed another way, 1-OBP = out %. In other words, OBP subtracted from the number 1 will yield the percentage of how often a hitter comes up to bat and uses up one of his team’s 27 outs for that game. A player can play all season, rack up impressive counting stats and still be using up far too many outs.

Maybe a tweak to how we think about outs and on-base percentage is in order. Dayn may be onto something here with this 1-OBP. I am going to take it a step further here and make it Outs/PA with "outs" defined as AB-H+CS+GDP. Baseball fans understand that outs are the only scarce resource in baseball. They understand that you only get 27 of them, and that each one you use puts you that much closer to running out of chances to score. So instead of tallying on-base percentage, which really only seems to resonate with folks who already buy in to advanced performance metrics, how about focusing on outs?

Discrediting Jimmy Rollins's 2007 MVP case by clamoring "but his on-base was only .344!!!" is obviously not sufficient. How about "did you know that Jimmy Rollins led all of Major League Baseball in outs in 2007?" Now that might help clarify things. To be sure, outs, on-base, outs per PA, etc. ignores what Bill James would call "advancement percentage" (which is really just slugging). It also fails to fully account for baserunning and clutch hitting. Still, tallying up outs per plate appearance is an instructive way to take a look at a major component of one's offensive makeup.

Here's a look at the top 10 and bottom 10 players in 2007 (minimum of 502 plate appearances) in Out %.

Bottom 10

Outs PA Out %

Rodriguez, I. 379 515 .736

Feliz 433 590 .734

Lopez, Jos 411 561 .733

Pena, T. 392 536 .731

Pierzynski 370 509 .727

Durham 383 528 .725

Uribe 408 563 .725

Molina 373 517 .721

Johjima 370 513 .721

Punto 386 536 .720

Top 10

Outs PA Out %

Ortiz, D. 384 667 .576

Helton 395 682 .579

Pena, C. 359 612 .587

Ordonez, M. 400 678 .590

Utley 362 613 .591

Rodriguez, A. 419 708 .592

Cust 302 507 .596

Posada 353 589 .599

Wright 427 711 .601

Jones, C. 362 600 .603

So let's break this down to one game to shed some meaning here. Dividing 27 by Out % tells us how many hypothetical plate appearances, or incremental run-scoring opportunities, a team full of one player would amass.

Out% 27/Out%

Ortiz .576 46.9

Pudge .736 36.7

To put these numbers into further perspective, let's look at some more 2007 figures. Here are the top-3 and bottom-3 scoring teams in the American League.

PA R R/PA

NYY 6,527 968 .148

DET 6,363 887 .139

BOS 6,426 867 .135

PA R R/PA

CHW 6,101 693 .114

KCR 6,139 706 .115

MIN 6,161 718 .117

Taking an average of these six R/PA figures, we get a figure of .128. Let's use this figure and once again compare Ortiz and Pudge. And remember, this is assuming that all else is equal between the two players (slugging, baserunning, etc).

Out% 27/Out% R/G

Ortiz .576 46.9 6.0

Pudge .736 36.7 4.7

Perhaps if the performance analysts focused their efforts on outs as both a counting and rate stat instead of tallying on-base, inroads could be made a bit more easily with mainstream figures. You and I know what a .400 on-base percentage means, but maybe that figure does not mean much to many others. On the other hand, if you know that a season full of plate appearances consists of 650-750 times at bat, and you know that David Ortiz only made an out just 384 times, that might start to mean something.

Likewise, by knowing that Rollins led the league in outs or that Pudge makes an out nearly three-quarters of the time he steps in the box, this too may help many fans start to evaluate offensive performance more appropriately.

Kicking and screaming about how too many do not understand what it takes to score runs does very little good. Rich's exchange with Buster Olney has led me to believe that trying to narrow the gap between the performance analysts and the mainstream is time better spent. Hopefully thinking about outs in this way furthers this cause.

| Baseball Beat | January 29, 2008 |

On the heels of the commissioner's office disclosing the final 2007 payrolls for the 30 major league clubs, I thought it might be instructive to analyze payroll efficiency by comparing team salaries to wins.

The payrolls shown below are for 40-man rosters and include salaries and prorated shares of signing bonuses, earned incentive bonuses, non-cash compensation, buyouts of unexercised options and cash transactions. In some cases, parts of salaries that are deferred are discounted to reflect present-day values.

The following table, ranked by club payroll (in millions of dollars), also includes team wins.

Team Wins $ Pay NYY 94 218.3 BOS 96 155.4 LAD 82 125.6 NYM 88 120.9 CHC 85 115.9 SEA 88 114.4 LAA 94 111.0 PHI 89 101.8 SF 71 101.5 CWS 72 100.2 STL 78 99.3 DET 88 98.5 HOU 73 97.2 BAL 69 95.3 TOR 83 95.1 ATL 84 92.6 TEX 75 78.9 OAK 76 78.5 CIN 72 73.1 MIL 83 72.8 MIN 79 71.9 CLE 96 71.9 ARI 90 70.4 SD 89 67.5 KC 69 62.3 COL 90 61.3 PIT 68 51.4 WAS 73 43.4 FLA 71 33.1 TB 66 31.8

The 2007 total payroll was $2,711,274,581 or approximately $90.4 million per team. The median was slightly higher than the mean. While the New York Yankees' record payroll of $218.3M added about $4.5M to the average, the teams below the median exerted an even greater impact on the mean than those above the mid-point. To put the payroll dollars in perspective, please note that MLB reported $6.075 billion in total revenues last season, or just north of $200M per team.

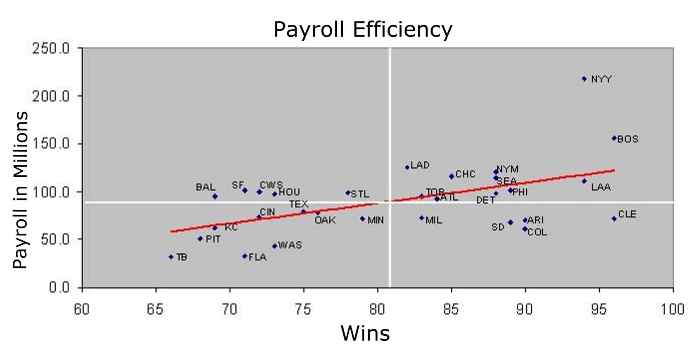

The information presented in the above table can be displayed in a graphic format, as shown below.

Based on this graph, we can categorize teams by the four quadrants as well as by the trendline. Starting in the upper-right end of the graph and moving clockwise, the northeast quadrant includes teams that won more games than average with a higher-than-average payroll. The southeast quadrant depicts clubs that won more games than average with a lower-than-average payroll. The southwest quadrant includes teams that won fewer games than average with a below-average payroll. The northwest quadrant lists teams that won fewer games than average with a higher-than-average payroll.

The red trendline indicates the positive correlation of team payroll and wins. The correlation coefficient works out to 0.5328. Teams above the line were less efficient and teams below the line were more efficient in terms of getting the most bang for their buck (as measured by payroll and wins).

Due to the fact that it's the goal of all teams to win the World Series, I'm going to excuse Boston from any list of inefficient clubs. Yes, the Red Sox paid up for their success, but it's hard to argue with the fact that they won it all. While Boston may not have been the most efficient in terms of regular-season wins vs. payroll, John Henry, Theo Epstein & Co. were clearly the most efficient in terms of winning World Championships – especially in view of the competition within the division.

Aside from the Red Sox, which teams were the most and least efficient last year?

There were five clubs that won more than 81 games with payrolls under the average of $90.4M. The best of the best was Cleveland, followed by Colorado, Arizona, San Diego, and Milwaukee. To their credit, the Indians, Rockies, and Diamondbacks all made the playoffs with COL advancing to the World Series. Congratulations to Mark Shapiro, Dan O'Dowd, and Josh Byrnes for doing the most with the least. Honorable mention goes to Kevin Towers and Doug Melvin.

The Los Angeles Angels, Philadelphia Phillies, Detroit Tigers, and Atlanta Braves also deserve praise for their payroll efficiency. The Angels and Phillies won division titles before falling in the first round of the playoffs. In the meantime, the Minnesota Twins, Washington Nationals, Florida Marlins, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Tampa Bay Rays should share the award for "doing the best while pinching pennies."

The clubs in the northeast quadrant and above the trendline had mixed results. All of these teams won more than their share of games, but they did so at a cost. In the case of the Yankees, George Steinbrenner, Brian Cashman & Co. did it at a huge cost. Two-hundred-and-eighteen-million dollars huge. New York's payroll was roughly $63 million higher than the No. 2 team (Boston), $128 million above the mean, and more than $186 million or nearly seven times above the lowest payroll (Tampa Bay). The Yankees made the playoffs so it wasn't a total loss. The Chicago Cubs won the NL Central and were the only other team in this group that at least got something in return for their large commitment to player payroll.

Moving to the least efficient teams, Baltimore, San Francisco, Chicago White Sox, and Houston failed miserably in their quest to buy a division title, much less a league or world championship. Mike Flanagan and Jim Duquette (Orioles), Brian Sabean (Giants), Kenny Williams (White Sox), and Tim Purpura (Astros) get the booby-prize award for (mis)managing payroll efficiency. Purpura was fired after the season and was replaced by current GM Ed Wade.

For more information on this subject, be sure to visit the Business of Baseball to check out Maury Brown's article By the Numbers: 2007 Player Payroll for the 30 MLB Clubs. Brown breaks down the data in even more detail, listing teams with the largest increases and decreases in player payroll from Opening Day while ranking playoff teams by cost per marginal win, a concept developed by the late Doug Pappas. In addition, Brown has recently published Unusual MLB Contract Clauses and Salary Arbitration.

| Baseball Beat | January 28, 2008 |

Dear Buster,

Thank you for taking the time to engage me in a lively debate about Jim Rice and his Hall of Fame qualifications. I don't know about you, but I believe this discussion is actually about much more than whether Rice should or shouldn't be elected to Cooperstown. I maintain that what we are really at odds over isn't Rice as much as the way we go about evaluating players when it comes time to vote for MVPs, Cy Young Awards, and the Hall of Fame. Rice just happens to serve as an excellent example of the differences in the thought processes that go (or should go) into these decisions.

I would be remiss if I didn't point out that you mischaracterized my comments on Rice and Bert Blyleven in the opening paragraph of your latest response. Rather than incorrectly interpreting what I wrote, perhaps you should have quoted me or linked to my articles so your readers could see for themselves what it is I said or didn't say.

In any event, in the spirit of Bob Rittner's guest column last week, I want to acknowledge our common ground as it relates to Rice. There is no question that Jim was a very good hitter for the vast majority of his career with the Boston Red Sox in the 1970s and 1980s. I would even go so far as to say that he was an outstanding hitter from 1977-1979 and in 1983 as well. Rice led the American League in total bases in all four of those seasons. That is a terrific accomplishment.

As you have pointed out on at least one occasion, Rice also topped the majors in RBI and hits from 1975-1986 and placed third in HR and fourth in OPS during that 12-year period. All of these rankings speak well of Rice's hitting prowess.

However, in order to fully understand and appreciate Rice's value and place in baseball history, I believe it is important to put his stats into their proper perspective. I would like to do that by focusing on context, consistency (in the application of the stats), and comparability (to other players). Allow me to refer to them as the three Cs.

Context

All players need to be viewed within the context of their era, league, team, place in the lineup, ballpark, and position. In the case of Rice, he played during a period that neither favored pitchers nor hitters. The second half of the 1970s and the decade of the 1980s were a fairly neutral time with respect to scoring runs. However, Rice benfited to a significant degree by playing his entire career in Boston. The team's home games were played at Fenway Park, which ranked as the AL's #1 or #2 most friendly ballpark to hitters in 13 of Rice's 14 full seasons (including nine years in which it was #1). As such, it follows that Rice's raw stats need to be adjusted.

Based on your skepticism of Adjusted OPS (or OPS+) as a measurement tool, I believe it is instructive to look at Rice's home (.320/.374/.546) and road (.277/.330/.459) splits to see how he performed in a more neutral environment. To the extent that Rice tailored his swing or game for Fenway Park, he should definitely get credit for his home performance above and beyond the park factor. This nuance is actually accounted for in Rice's career OPS+ mark because it only dings him about 3.5% or one-half of the average park factor of 107 and not for his total outperformance at home.

Sure, Carl Yastrzemski and Wade Boggs took advantage of Fenway, too. But Yaz and Boggs both had higher peaks and better career totals than Rice. Yastrzemski was a better left fielder and Boggs played a more vital defensive position to boot.

Context is also an important consideration with respect to counting stats such as runs batted in and hits. Opportunities play a big role in both. I covered these matters in detail two weeks ago and believe many of Rice's counting stats were largely a function of his opportunities. His career totals were definitely solid but not overly special. Combining counting stats with rate stats allows us to judge quantity and quality. A player's longevity, efficiency, and peak value are all part of the puzzle.

A player's position is another contextual item. The fact that Rice played LF for about 75% of his career and DH for the other 25% – and was generally viewed as a slightly below-average fielder – means he was basically a hitter and little else. I'm not arguing that he didn't hit; instead, I'm just trying to put his offensive contributions in their proper light. All else being equal, players on the left side of the Defensive Spectrum (DH | 1B | LF | RF | 3B | CF | 2B | SS) are less valuable than those on the right side.

Consistency

In order to have meaning, statistics and statistical profiles need to be applied consistently from one player to the next. If using a 12-year period to measure Rice's worth is fair as you suggest, should we not apply this same window to all time frames and players?

Joe Carter, for example, led the majors in RBI for four consecutive 12-year periods (1984-1995, 1985-1996, 1986-1997, and 1987-1998). He also led the majors in HR for those first two 12-year periods. Carter was a better baserunner than Rice, played on two World Series championship teams, and slugged one of the most famous home runs in the history of the game. The point of this exercise isn't to suggest that Carter is a HOFer; rather, it is to downplay the significance of Rice's rankings during his best dozen years.

You have also made a big deal out of Rice's standing in so-called MVP Shares. Along the lines of your disdain for OPS+, "if this [is] your be-all, end-all statistic, keep in mind that" . . . Dave Parker had more MVP Shares than Jim Rice, Juan Gonzalez had more MVP Shares than Rickey Henderson, and George Bell had more MVP Shares than Robin Yount even though the latter won two MVPs and was a first-ballot HOF selection.

Comparability

Is Rice the best player not in the Hall of Fame? Is he even the best outfielder not in the Hall of Fame? Seriously, is Rice really better than Andre Dawson, Dwight Evans, Dale Murphy, and Dave Parker? I don't see it myself. I will concede that a proponent of Rice could make a case that he is as good as these four outfielders (none of whom are in the HOF), but I can't for the life of me understand how somebody could claim that he was sufficiently better and deserved enshrinement over the others. By my way of thinking, if Rice is a Hall of Famer, then so are Dawson, Evans, Murphy, and Parker.

POS PA TOB TB AVG OBP SLG OPS+ WS WARP3

Dawson CF-RF 10769 3474 4787 .279 .323 .482 119 340 105

Evans RF 10569 3890 4230 .272 .370 .470 127 347 120

Murphy CF-RF 9040 3125 3733 .265 .346 .469 121 294 86

Parker RF-DH 10184 3451 4405 .290 .339 .471 121 327 85

Rice LF-DH 9058 3186 4129 .298 .352 .502 128 282 83

If Win Shares (WS) and Wins Above Replacement Player (WARP3) are too esoteric, that's fine. But please note that both measures account for defense as well. Three Win Shares equal one win. As such, both Win Shares and WARP paint a similar picture. Notably, scores of 300 WS and 100 WARP generally equate to Hall of Fame-caliber careers. There are exceptions on both sides of these magic numbers, particularly in the case of players that had short careers but extraordinary peaks (like Sandy Koufax).

I will grant that Rice may have been the best hitter of the fivesome (by the narrowest of margins), but he played the least important position and was the least competent defensively. Dawson, Murphy, and Parker were certainly better baserunners at their peaks, giving each of them a modest plus in this department as well.

Mix in the MVPs and Gold Gloves if you will, shake it all up, and how can one justify Rice's Hall of Fame worthiness over his fellow outfielders? A rational analysis would suggest it is virtually impossible. If you're a big Hall guy, then go ahead and continue to vote for Rice. But you should be voting and pushing for Dawson, Evans, Murphy, and Parker, too.

Although I don't expect to sway your vote as it relates to Rice, I'm hopeful that our debate will give you (and others) pause when filling out your ballot in the future. All of us love stats in one form or fashion, but they are most relevant when viewed in their proper context and applied consistently so that player comparability can be truly evaluated.

Respectfully submitted,

Rich Lederer

| Command Post | January 25, 2008 |

The first pitch is thought to be very important in an at-bat. Young pitchers are taught to get ahead in the count and that the balance of an at-bat hinges on whether this pitch is a strike or ball. Throwing first pitch strikes is a mark of a good pitcher, and one of the most infuriating things to watch is a pitcher who can't throw first pitch strikes. Today I want to look at the value of the first pitch and what happens to those pitches after they leave the pitcher's hand.

Of the twelve counts, there are six (anything without three balls or two strikes) where the at-bat is guaranteed to continue if the batter does not swing at the pitch. Assuming no swing, here are the chances of seeing a fastball in a subsequent count, based on whether the pitch is a ball or a strike. The chart is based on what will happen in the future based on what happens in the current count. So starting in an 0&0 count, if pitch is a ball, there is a 59% chance the next pitch (in the 1&0 count) will be a fastball, but if the first pitch is a strike, there is a 48% chance of a fastball being thrown in an 0&1 count. The swing of 11% measures how valuable a strike is in each count, in terms of potentially seeing fastballs.

Count FB% If Ball If Strike Difference 0&0 0.59 0.59 0.48 0.11 0&1 0.48 0.49 0.47 0.02 1&0 0.59 0.70 0.49 0.21 1&1 0.49 0.59 0.44 0.15 2&0 0.70 0.78 0.59 0.19 2&1 0.59 0.76 0.47 0.29

The first pitch of an at-bat sets the tone of the at-bat due to the conditions it creates for ensuing pitches. In terms of seeing a fastball, there is relatively little difference between an 0&1 count and a 1&0 count, but if the first pitch is a strike the pitcher has put himself in a good position as the count progresses. An 0&1 count is a clear pitcher's count and even if he throws a ball in that count, a 1&1 count is still a pitcher's count and the pitcher arrived there through pitcher's counts. However, if the first pitch is a ball, the pitcher is now at a slight disadvantage because while 1&0 is a neutral count, it has the potential to turn into an extreme hitter's count. If the pitcher does throw a strike and evens the count at 1&1, he would have presumably been under more pressure to throw a strike after the first pitch. Sal Baxamusa explores this type of pitch sequencing in more detail here and actually finds that when batters put a 1&1 pitch into play, they do better when the order was strike-ball, despite apparently having an advantage in the other sequence.

Anyway, that tangent was just to establish the importance of the first pitch of an at-bat. Now that we have a rough idea of its importance, lets look at what actually happens on the first pitch. The table below shows all first pitches, broken up by pitch type, along with certain measurements about each pitch type. Freq. is how often the pitch was thrown, S% is strike frequency, or strikes balls in play/all pitches, Called% is called strikes/total pitches, Swing% is how often the batter swung at a pitch, Sw% is how often batters swung and missed when they swung, Fo% is how often batters fouled balls off when they swung, and SLGBIP is slugging percentage on balls in ball, including home runs.

Pitch NP Freq. S% Called% Swing% Sw/Swing Fo/Swings SLGBIP CH 6271 0.11 0.55 0.23 0.33 0.33 0.28 0.557 CB 6437 0.11 0.55 0.37 0.18 0.29 0.31 0.552 FB 35131 0.60 0.60 0.32 0.29 0.13 0.44 0.551 SL 10728 0.18 0.60 0.30 0.31 0.26 0.35 0.506 ============================================================================ Tot 58567 1.00 0.59 0.31 0.28 0.19 0.40 0.543

Fastballs are thrown slightly more often as first pitches than overall (60% on first pitches vs. 56% overall) which makes sense with pitchers trying to throw a strike and get ahead in the count, but generally, the rates are pretty similar for how often each pitch is thrown as a first pitch and overall. The most interesting thing to me on this chart is how often batters swing at a first pitch curveball. As a batter, a curveball isn't necessarily a pitch you would expect to see at the start of an at-bat, which probably explains the low number of swings because batters would only swing if it were a very hittable curve. This seems like a great example of how not being predictable helps a pitcher tremendously though. By occasionally throwing a curve as the first pitch, the pitcher is sometimes able to get a free strike because the batter swings so rarely.

A first pitch slider would also come as somewhat of a surprise from most pitchers, yet batters swing at that pitch relatively frequently. A slider looks more like a fastball immediately out of a pitcher's hand, so perhaps batters are fooled into swinging because of this. This would explain the low SLGBIP, because unlike curveballs where a batter is swinging preferentially at pitches he likes, with sliders, batters are swinging at a pitch they think is a fastball, but are forced to adjust their swing once the slider breaks. Overall, curveballs that are put in play lead to a SLGBIP of .484, but on the first pitch their SLGBIP jumps to .552, similar to SLGBIP for fastballs on first pitches, which supports the idea that batters are good at selecting which curves to swing at on the first pitch. One other interesting thing in the table is what happens when batters swing at certain pitches. Batters rarely swing and miss at first pitch fastballs, but they foul off those pitches so frequently that fastballs are only slightly less likely to be put in play than the other three pitch types. I'm unsure why batters foul off so many fastballs, but it might be because batters are be willing to swing at a wider range of locations and speeds if they recognize the pitch as a fastball.

In the past, I've looked at how batters of different quality are approached by pitchers. Using that method again, I wanted to see if there are differences in how these batters were pitched to on the first pitch as well. In the table below, columns labeled with -1 are the frequencies for first pitches while the columns labeled with -R are the frequencies for all other pitches.

SLG FB-1 FB-R SL-1 SL-R CB-1 CB-R CH-1 CH-R >=.500 0.58 0.52 0.20 0.21 0.12 0.11 0.11 0.15 .499-.400 0.58 0.54 0.19 0.20 0.12 0.11 0.11 0.15 <=.399 0.68 0.58 0.16 0.19 0.08 0.10 0.08 0.13

I grouped hitters based on their Marcel projected SLG for the 2007 season and while the windows I used to group hitters are wider than in my previous examination, the overall idea is almost identical. Narrower windows would just show a more gradual increase in off-speed pitches as batters improved, but one other thing thats interesting is that it almost is as if there is a plateau for batters with a .400 SLG. A .400 SLG seems to be the level of hitter that prompts a pitcher to alter his first pitch repertoire.

Recently, I've been looking at different groups of pitchers and seeing if there are differences in the way they pitch based on their age and the quality of their fastball. I created two group, those pitchers 34 and older and those 24 and younger, and then split those two groups into pitchers with an average fastball speed of more than 91 MPH and an average speed less than 91 MPH. The table below shows just the first pitch fastball frequency for each type of pitcher throwing to each type of hitter, along with the average of all first pitches for each pitcher type.

SLG Young/Slow Old/Slow Young/Fast Old/Fast >=.500 0.54 0.59 0.61 0.48 .499-.400 0.54 0.56 0.63 0.49 <=.399 0.66 0.62 0.69 0.63 ================================================== Avg. 0.56 0.57 0.63 0.51

The same pattern is evident here as well, with the bad hitters seeing a lot more fastballs than the other two groups of hitters. This trend holds regardless of the age of a pitcher or the quality of his fastball and the big difference between groups of pitchers is how many extra fastballs they throw to bad hitters. Even though there isn't a tremendous amount of difference between a 1&0 count and an 0&1 count, the first pitch is a crucial pitch in setting the tone of an at-bat and the importance placed on it is probably justified because of this.

| Designated Hitter | January 24, 2008 |

I think the most productive discussion is the one where, after spirited debate, each person argues in favor of his opponent's case. And the least productive is when each person comes away convinced he is right and has demolished his opponent's arguments.

I would like to spin off from the Mark Armour In Defense of the Hall of Fame thread to consider the differences between traditional baseball writers and the contemporary analytical community. The distinction is not always stark; I always considered Leonard Koppett an analyst, and I enjoyed reading Arthur Daley, Roger Angell and others who brought the game to life for me and often provided a sense of intimacy with the players. Often, they brought to the issues facing the game an intellectual perspective that stimulated thinking on subjects like expansion or the DH rule or the Curt Flood case.

And often they were fine writers whose humor and ability to delineate the character of particular people expressed the mood of the game and enhanced the joy of watching and thinking about it. I still alternately laugh and tear up reading Larry Ritter's "The Glory of Their Times" even while cringing at some of the cliches from Lefty O'Doul and others. Periodically I listen to excerpts on tape from some of Ritter's interviews, and hearing Sam Crawford describe Rube Waddell or barnstorming in the mid-west, or Hans Lobert discussing Honus Wagner's kindness to the rookie or Fred Snodgrass defending himself and Fred Merkle from the criticism both have endured makes the game real and vibrant. I really think it is required reading (or listening) for any baseball fan.

But in my mind, with rare exceptions, these were not really analysts. They were writing about the game as literary figures, creating plots and climaxes and denouements and using all the approved techniques of novelists. What mattered was the story. Baseball was the arena in which to exhibit character and moral principles. And stories were built around those issues. Players rose to the occasion or choked, were heroes or goats, overcame all sorts of obstacles and odds or failed to deliver for their teammates and fans.

The stories were exciting and sometimes even had whispers of truth in them, but they had nothing to do with what was really happening because most of what really happens is mundane and not terribly exciting. The job of these writers was to extract the drama from the details and to make the story as interesting as possible.

After a time, certain themes (often reflecting virtues like sacrificing for the team or out-thinking the opposition) became fixed orthodoxy, elevating strategies like sacrifice bunts and moving runners over and the psychology of winning to the status of gospel or leitmotifs in most story lines. I have sometimes speculated that in the first decades of the 20th century when the sport was considered disreputable by many and the province of hooligans, in an effort to make baseball more respectable, books and articles by Christy Mathewson (or his ghostwriter) and others focused on the "inside game," the intellectual components of baseball, and praised the cleverness and psychological maneuverings of manager John McGraw. The effect was not simply to make baseball a more intellectually and morally respectable game, but it simultaneously established the basic principles that hardened into "the Book."

I was satisfied with this sort of baseball writing and raised my son with my recollections of baseball in the 1950s and discussions of columns in the mainstream newspapers and books of the 1970s. When he was a teenager, he returned the favor by introducing me to Bill James. And in my mid-40s, I became dissatisfied. Of course, James was interested in the stories and anecdotes. (In fact, I was sometimes irritated when I expected a hard analysis of some player's ranking in his Abstract only to be treated instead to some tangent about Dick Williams socializing with Sal Bando.) But alongside were questions and a serious attempt to find some way to answer them. I did not always follow the math, but I did understand the logic, and it was exciting. I still read the columns but they were not enough. The columns were about human interest and could have been on any subject. James and company were about baseball specifically.

In a way, the sabermetricians have created a problem for the traditional columnists. The early journalists always used stats, but they were rarely the key to any argument, and they generally were rather simple and commonly understood. They were the details that lent depth to a story, like descriptions of scenery and characters' physical traits in a novel. The journalists' audience, training and medium are not conducive to detailed statistical analysis. When Murray Chass mocks VORP and the like, I think he is actually making a valid point (I am really biting my tongue now) in the context of what would be acceptable in a mass circulation newspaper.

Of course elements of sabermetrics can and should be incorporated into the columns, and the movement has earned the right to be respected by columnists. Some have and do, and even those who ignore or resist progressive statistical analysis are clearly influenced by it, at least on the margins. OBP has almost gained the status of BA, albeit not quite, even among traditionalists. But to ask them to accept its approach as authoritative or to defer to its judgments is futile. They can include OBP, even ERA+ or OPS+ in their assessments, but their style precludes the charts and graphs and more detailed statistics. You don't ask Tolstoy to include a chart of the nationalities of prisoners in "War and Peace."

And the reason is not that they are wrong. It is that the two groups are engaged in different purposes. And while it is easy for sabermetricians to apply the approach of traditionalists to liven up their writings, it is not so easy for traditionalists to incorporate statistical models and arguments in theirs. So there is frustration on both sides.

When a traditional columnist writes an article defending a position, sabermetricians attack using all the tools at their disposal, and sometimes with sarcasm and nastiness. If the columnist dismisses their arguments, they pile on. But it is even worse if he tries to meet them on their own grounds. Without the expertise, his statistical arguments appear juvenile and then the attacks often turn vicious and personal. A successful career journalist, out of his depth in this kind of debate, finds himself the object of mockery, and with the internet, there is now a public forum for the ridicule. The problem is there is no common ground. The traditional journalist is not wrong; he simply has a different purpose, and to critique him is like arguing with Shakespeare that Hamlet should have compromised with Claudius or brought him before a board of inquiry.

When an issue like the Hall of Fame elections arises, the problem is magnified because for statistically minded analysts there are objective criteria from which to begin the discussion. But to many traditionalists, the key word in the discussion is "Fame" as in who do people know, who had an impact on the story.

Jack Morris exemplified qualities that suggest he is a Hall of Fame character; Bert Blyleven did not. Jim Rice dominated because that is the story line, and for anyone who lived in his era, it makes perfect sense. It does not matter to those who are now voting if the statistics belie the claim.* When I watched a Yankee game and Rice came to the plate, I was scared. I was not as worried when Dwight Evans was at bat. I may have been wrong, but Rice felt like a star and Evans a supporting player. To say the journalists are wrong does nothing to advance the discussion because these players are first and foremost literary figures to them. You and I may know that Watson and Crick were far greater men than Alexander the Great and Napoleon, but in the pantheon of human heroes, you can bet Alexander will get in first, and nobody is going to identify Crick as Crick the Great.

I do think there can and ought to be dialogue between the "schools of thought," but I think it requires mutual respect for and recognition of the divergent approaches. The dichotomy is probably not as dramatic as I have suggested, but I do think it would help if in debating points each side tries first to ascertain where there is common ground so they can talk to each other rather than at each other.

*I am reminded of reading that the Medieval books about the Lives of the Saints were almost entirely fictitious as narratives of events. Their truth was in the morals of the stories, the standards of behavior and faith the saints represented. So a particular saint may not even have existed, but the virtue of courage or charity he exemplified did exist and was true.

Robert Rittner is a retired high school history teacher from Westchester county, NY, now living in Clearwater, Florida. He has been a baseball fan since 1951, moving to Florida in part because of the opportunity to watch baseball regularly. He is also starting to hit a little better in his softball league.

[Additional reader comments and retorts at Baseball Primer Newsblog.]

| Baseball Beat | January 23, 2008 |

Rob Neyer's wish ("here's hoping it lasts the rest of the winter") is coming true. Buster Olney responded to my article yesterday.

Rich Lederer has another post in our ongoing Jim Rice debate. Rich writes, "Despite protestations to the contrary, those of us who oppose Rice's candidacy are not viewing him through a "time-machine prism" or "offensive formulas tailored for the way the game was played in the '90s."The quoted words are mine. Rich goes on to cite an example of skeptical words written about Rice in 1985: "Virtually all sportswriters, I suppose, believe that Rice is an outstanding player. ... If someone can actually demonstrate that Jim Rice is a great ballplayer, I'd be most interested to see the evidence."

Those words belonged to Bill James, whom Rich and I both view (I assume) as an extraordinary visionary.

With this, Rich absolutely demonstrates one of my primary points about Rice. Bill James was someone who was years (decades?) ahead of his time in evaluating the value of walks and on-base percentage. But he wasn't only ahead of sportswriters, but ahead of managers, coaches, general managers and scouts, who placed value judgments on what they viewed as the proper approach to the game. Jim Rice, as a middle-of-the-order slugger, was expected to drive in runs. That's how he was evaluated, that's what he was expected to do, that's what he did well, that's why he was among the game's highest-paid players.

Guys who hit in the middle of the lineup and drew a lot of walks were viewed by the old guard, in some respects, as selfish players who refused to put their batting average at risk for the betterment of the team. I spoke about this last week with Jayson Stark, in regards to Mike Schmidt, a slugger who drew a lot of walks, and Stark specifically remembered Schmidt -- a '70s star who really played a 21st style of baseball, with lots of home runs, walks and strikeouts -- drawing criticism from peers for his approach. Sure, a Schmidt or Rice base on balls leading off an inning was a good thing, but if there were runners on base, the feeling was that they needed to swing the bat; they needed to drive in runs. Ted Williams, another slugger who drew a lot of walks, was subject to the same sort of scrutiny, as Peter Gammons recalled in a phone conversation the other day. Rice, on the other hand, knew he was expected to drive in runs, as Peter recalled.

Just two players drove in 85 or more runs in 11 seasons in the 12-year period of 1975-1986, and Rice almost certainly would've been 12-for-12 if not for the 1981 strike. In the eyes of the people he played for, he did exactly what a middle-of-the-order hitter should do. Honing his command of the strike zone and drawing walks, alongside all of those hits he generated, was not what his employers wanted him to do.

James ran the numbers and recognized the flaws in this manner of thinking. He was ahead of his time, and now almost everybody in the game has embraced his view. The thinking of hitters and evaluators has completely shifted: A middle-of-the-order hitter who refuses to take walks and trust the hitters behind him to drive in runs is now viewed, within the game, as being selfish.

But James cannot both be a visionary and an example of evaluation at that time, as Rich has used him above. It's one or the other. By the standards of the time -- and RBI unquestionably was the primary standard for the sluggers who played and for those who managed and evaluated -- Rice was exceptional, and he honed his game to that end. He swung the damn bat. The managers he played for and against respected him for it, the executives he played for paid him handsomely for it, and given the standards of his time, the sportswriters rewarded him with a staggering portion of MVP votes. In the James quote above, he takes issue with sportswriters, but he easily could've inserted "managers" or "general managers" or "players" into that sentence.

The RBI way of thinking seems, these days, as outdated as drawing blood with leeches. But Rice did his work within those parameters, and within that context, he was among the best in the game. We cannot go back now and say, Hey, Jim, remember all those times when you swung at pitches just off the plate as you tried to put the ball in play and drive in those runners, because you thought it was your job, because Derrell Johnson and Zimmy and John McNamara and their bosses thought it was your job? Well, we're here to tell you now, in the 21st century, that was a bad idea. You should've taken the walk. So forget it, you played the game the wrong way. We know this because your Adjusted OPS+ -- a statistic no ballplayer or manager or GM ever heard of until after you retired -- is poor. Oh, sure, you drove in a lot of runs, but we're here to tell you, 20 years later, that RBI is a junk stat.

I majored in Civil War history, so please excuse this completely inappropriate analogy between war and baseball: This is like suggesting now that Ulysses.S. Grant was a lousy general because he lost staggering numbers of men attacking entrenched positions. Rather, we should attempt to view his decisions through the evolving technology and tactics of war. Through that horrible vantage point, he was necessarily a tough and brilliant general.

No one can dispute that Rice was either the best or among the best RBI men in the AL for more than a decade, and for power hitters, this was the stat that defined them. That was the accepted vantage point of the time. To retroactively dismiss RBI seems utterly insane. Nicolaus Copernicus thought the sun was the center of the universe, wrongly, but that doesn't mean he wasn't exceptional for his time.

(And in case anyone hasn't noticed, I have not used the word "fear" one time in this conversation with Rich. At least I think I haven't.)

Olney is zeroing in on RBIs (or "RBI" as my Dad taught me). Although it is far from my stat of choice, let's take a look at the American League leaders in RBI since 1950:

1950--Walt Dropo 144

Vern Stephens 144

1951--Gus Zernial 129

1952--Al Rosen 105

1953--Al Rosen 145

1954--Larry Doby 126

1955--Ray Boone 116

Jackie Jensen 116

1956--Mickey Mantle 130

1957--Roy Sievers 114

1958--Jackie Jensen 122

1959--Jackie Jensen 112

1960--Roger Maris 112

1961--Roger Maris 142

1962--Harmon Killebrew 126

1963--Dick Stuart 118

1964--Brooks Robinson 118

1965--Rocky Colavito 108

1966--Frank Robinson 122

1967--Carl Yastrzemski 121

1968--Ken Harrelson 109

1969--Harmon Killebrew 140

1970--Frank Howard 126

1971--Harmon Killebrew 119

1972--Dick Allen 113

1973--Reggie Jackson 117

1974--Jeff Burroughs 118

1975--George Scott 109

1976--Lee May 109

1977--Larry Hisle 119

1978--Jim Rice 139

1979--Don Baylor 139

1980--Cecil Cooper 122

1981--Eddie Murray 78

1982--Hal McRae 133

1983--Cecil Cooper 126

Jim Rice 126

1984--Tony Armas 123

1985--Don Mattingly 145

1986--Joe Carter 121

1987--George Bell 134

1988--Jose Canseco 124

1989--Ruben Sierra 119

1990--Cecil Fielder 132

1991--Cecil Fielder 133

1992--Cecil Fielder 124

1993--Albert Belle 129

1994--Kirby Puckett 112

1995--Albert Belle 126

Mo Vaughn 126

1996--Albert Belle 148

1997--Ken Griffey Jr. 147

1998--Juan Gonzalez 157

1999--Manny Ramirez 165

2000--Edgar Martinez 145

2001--Bret Boone 141

2002--Alex Rodriguez 142

2003--Carlos Delgado 145

2004--Miguel Tejada 150

2005--David Ortiz 148

2006--David Ortiz 137

2007--Alex Rodriguez 156

If RBI is an indicator of greatness, why is it that only nine leaders (covering 11 seasons) from 1950 to 1994 (chosen to accommodate eligible candidates) have been inducted into the Hall of Fame? Sure, Jim Rice led the AL in RBI twice. But so did Al Rosen, Jackie Jensen, Roger Maris, and Cecil Cooper (as well as Vern Stephens if we also include 1949). Moreover, Cecil Fielder and Albert Belle each led the league three times. None of these players are in the Hall of Fame. In fact, other than Maris, not a single one of these players ever received even 10% of the vote. Cooper failed to get any votes at all, while Fielder was named on just one ballot.

The most damning evidence against Rice in the case of RBI is the fact that Eddie Murray is the only player who ever led the league during Rice's 14 full seasons and was later elected to the Hall of Fame. George Scott, Lee May, Larry Hisle, Don Baylor, Hal McRae, Tony Armas, Don Mattingly, Joe Carter, George Bell, Jose Canseco, and Cooper all led the league in RBI and only Donnie Baseball ever picked up 5% or more of the vote.

As far as Olney's hypothetical comments to Rice (see the italicized statements above), nobody said or is saying that he "should've taken a walk" or that he "played the game the wrong way." We're only evaluating what it is Rice did and what it is he didn't do. That's all. Roberto Clemente, Rod Carew, George Brett (save 1985-1988), Paul Molitor, and Tony Gwynn didn't walk much either, yet I don't think you will find many people who believe these players are undeserving of the Hall of Fame.

The fact that "no ballplayer or manager or GM ever heard of" Adjusted OPS "until after (Rice) retired" suggests that he would have fared better in this stat had he only known about it. That not only seems silly to me but contrary to any and all evidence, such as the fact that Rice walked at the same rate with nobody on base and with runners in scoring position (7.0% of plate appearances in both cases) [hat tip to tangotiger]. Look, OPS+ is a measurement tool. And it's not overly complicated either. You see, when you get right down to it, the factors that go into Adjusted OPS – singles, doubles, triples, home runs, walks, hit-by-pitches, and outs – have been tracked since the turn of the previous century. OPS+ simply takes these stats and adjusts them for context (i.e., era, league, and ballpark). Is it a perfect stat? No. But it is a telling stat and one that shouldn't be dismissed, whether Rice and others knew of it or not.

| Baseball Beat | January 22, 2008 |

In Rob Neyer's Friday Filberts, he made a keen observation that perhaps has been lost in the debate over Jim Rice's Hall of Fame worthiness.

• Rich Lederer and our own Buster Olney have devoted space this week in their respective venues to an entertaining back-and-forth that's ostensibly about Jim Rice but is really about something much deeper than one man's Hall of Fame candidacy. Highly recommended for the quality of the writing alone, and here's hoping it lasts the rest of the winter.

I totally agree with Rob's take on this matter. I'm not nearly as interested in whether Rice gets elected to the HOF as I am in shaping the thought process. If Rice gets in, he gets in. I'm not going to lose any sleep over the matter. I just don't want to be standing in the way of the cattle call when Andre Dawson, Dale Murphy, Dave Parker, Dwight Evans, and even George Foster storm the front door to Cooperstown.

Although Olney and I disagree on the bottom line (i.e., Rice's inclusion or exclusion), in some ways, it's neither here nor there. What is here and there is the way we go about evaluating players. Despite protestations to the contrary, those of us who oppose Rice's candidacy are not viewing him through a "time-machine prism" or "offensive formulas tailored for the way the game was played in the '90s."

For proof on this very subject, let's take a look at what Bill James had to say about Rice in the 1985 Baseball Abstract:

Virtually all sportswriters, I suppose, believe that Jim Rice is an outstanding player. If you ask them how they know this, they'll tell you that they just know; I've seen him play. That's the difference in a nutshell between knowledge and bullshit; knowledge is something that can be objectively demonstrated to be true, and bullshit is something that you just "know." If someone can actually demonstrate that Jim Rice is a great ballplayer, I'd be most interested to see the evidence.

How great is that? I mean, Bill's not saying that now. Instead, he made that statement 23 years ago while Rice was still playing!

And, again, it's not about Rice per se. It's about the search for the truth.

James opened up our eyes – and our minds – by challenging the conventional wisdom and proving it wrong in so many cases. More than anything, he taught us to ask questions. Thanks to Bill, we have learned the importance of dealing with questions rather than answers.

With the foregoing in mind, here are eight questions for Rice's supporters and undecided voters to ponder when filling out their ballots next year:

- To what extent were Rice's career totals positively affected by playing home games his entire career at Fenway Park, known as a hitter friendly ballpark?

- If Rice gets credit for leading the majors in RBI from 1975-1986, then shouldn't he be debited for topping all players by an even wider margin in GIDP during that same period?

- Was Rice as great as his RBI totals would indicate or were they heavily influenced by the fact that he ranked in the top seven in runners on base in nine of those 12 years?

- Can we ignore that Rice produced the second-most outs during these same dozen years?

- Did Rice play a difficult defensive position?

- Was Rice a Gold Glove-caliber fielder?

- Was Rice a "plus" baserunner?

- In other words, was Rice really as good as advertised?

The greatest change since Rice's playing days hasn't been the acceptance of OBP as a noteworthy stat as it has been in recognizing that many long-held beliefs based on traditional stats are as much a function of the era, league, team, lineup, and ballpark as anything else. Stats don't tell the entire story but the *right* stats tell us most of what we need to know.

Take, for instance, Bert Blyleven and Jim Palmer. One of the knocks against Blyleven is that he wasn't one of the most dominant pitchers of his era. The conventional wisdom says that Palmer was dominant and Blyleven wasn't. To that, I say, "Really?"

Can we accept a stat that measures the number of runs that a pitcher saved versus what an average pitcher would have allowed (adjusted for park differences) as a reasonable proxy to judge effectiveness?

Well, if we can, what would you say if I told you that Blyleven led all pitchers in Runs Saved Against Average from 1973-1977? Yes, all pitchers. Not just Palmer. But Tom Seaver, Phil Niekro, Gaylord Perry, Steve Carlton, Nolan Ryan, and Don Sutton, too?

Furthermore, what would you say if I told you that Palmer won three Cy Young Awards during those five years and that Blyleven received one third-place vote during that same time? I mean, would you scratch your head and wonder if the Cy Young voting process was flawed? If nothing else, wouldn't you want to consider facts outside the simple tasks of counting CYA and All-Star games?

Moreover, what would you say if I told you that Blyleven led the majors in RSAA in not just one five-year period but in four consecutive five-year periods? Yes, it is a fact. Blyleven saved more runs than any pitcher from 1971-1975, 1972-1976, 1973-1977, and 1974-1978. It seems to me that he was probably the best pitcher during that time period, no? If Bert wasn't the greatest, he was certainly one of the most dominant, don't you think?

In the spirit of asking questions, is it possible that Palmer benefited by working his home games in a ballpark that was more friendly to pitchers than Blyleven? The answer is "yes." Palmer pitched in Memorial Stadium while Blyleven toiled in Metropolitan and Arlington Stadiums. The difference in park factors averaged a tad over 7% per year.

Is it also possible that Palmer benefited by having a superior defense playing behind him? During his Cy Young seasons, Palmer had Mark Belanger at shortstop, Bobby Grich at second base, and Paul Blair in center field. He also had Brooks Robinson at third base in two of those three years. Belanger, Grich, Blair, and Robinson are among the best defensive players at their position in the history of the game. Blyleven, on the other hand, had Danny Thompson and Rod Carew as his middle infielders.

You see, there are answers in these questions. Better yet, knowledge.

As for my *debate* with Olney, I'm proud that we behaved in a mature and civil manner while arguing the message and not the messenger. Writing opposing views in a public discourse like this is healthy and can go a long way in our search for the truth, which is what these exercises should be all about.

| Baseball Beat | January 21, 2008 |

My pal Alex Belth wrote a terrific literary piece on Ray Negron, entitled "Inside Man: A Bronx Tale." Although he published it as a Bronx Banter exclusive, the four-part series could have easily appeared in the New York Times Magazine or the New Yorker. It is that good.

Negron has been with the Yankees off and on for more than 30 years. He started as a batboy in the early 1970s and worked his way up to special advisor to George Steinbrenner. As Belth wrote, "Negron has done everything from shine the players' shoes and collect their dirty jockstraps, to bring them food from their favorite restaurants and park their cars. He has been an agent, an actor, an advisor, and a liaison; a confidant, a sounding board and a whipping boy to some of the biggest egos in the game. He is whatever he needs to be."

Here is an excerpt from the story, which was written last summer:

Ray is philosophical about his future with the Yankees. "Let's face facts, I'm not going to be with the Yankees forever, so I'm trying to find a niche for myself. Look, the Boss has told me that as long as he's here, I'd always be a Yankee, and that's all I can go by. George is here, I'm a Yankee, and that's the bottom line. Someday, he might not be here—or I may not be here—then the new people, the new regime might say, 'Okay, that's enough, get him outta here.' And I've come to grips with that."

Due to the unedited quotes, the timely article, which comes complete with photos and illustrations, is recommended for mature audiences. Hurry over to Bronx Banter and read about Negron, Steinbrenner, Reggie Jackson (who Ray nudged out of the dugout for a curtain call after the slugger hit his third consecutive home run in the deciding game of the 1977 World Series), Dwight Gooden, Darryl Strawberry, and much more.

Tulowitzki (.291/.359/.479) slugged 24 HR while driving in 99 runs and scoring 104 times. He placed second (behind Ryan Braun) in the National League Rookie of the Year balloting and should have won a Gold Glove for his outstanding fielding. He topped all shortstops in fielding percentage (.987) and ranked first at his position in Jon Dewan's Plus/Minus fielding ratings.

My former partner Bryan Smith recently brought to my attention a scouting report I gave in a One on One: Amateur Hour conversation between us in May 2005.

Tulowitzki is the real deal. I wouldn't hesitate taking him number one in the draft. He is that good. Everybody knows the comparisons to Bobby Crosby. He's got the size, a powerful arm, a good glove, 4.2 speed, and plus power. What might not be so well known is that Troy also has the energy, enthusiasm, and leadership skills reminiscent of Miguel Tejada. This is a guy who could make it to the majors by September 2006 and has as good a shot at being named Rookie of the Year in 2007 as anybody.

Despite the protestations of mainstream writers to the contrary, they have trouble wrapping their heads around the idea that a hitter can be valuable without flashing a light-tower stroke. These scribes will whine that fans and the league have made a fetish out of the home run, but then cast more ballots for the inferior Jim Rice than they do for Raines. All too often, we’re subjected to generational spats over whether the Moneyball approach to offense (i.e., waiting for your pitch and hitting it out of the park when you see it) is better than the traditionalist’s beloved “small ball” game (bunts, hit-and-run, stealing bases, being aggressive at the plate). We know that the former leads to more runs, but it’s odd that the shrillest advocates of the latter would abandon Raines, who played the small-ball way better than almost anyone else. Somehow, though, they’ve turned their backs on him.So, apparently, power matters to the writers except when they’re grouchy over the fact that bloggers/Web-based writers/stat geeks/kids on their lawns happen to like power.

Got it? It all raises the possibility that they don’t believe their own words. The truth is that Raines is a Hall-of-Fame caliber player regardless of how you think the game should be played. That he’s been so inexcusably dismissed by the writers speaks to the flawed nature of the process. Fans, however, are free to recognize Raines as one of the greats regardless of whether or not he ever gets the Cooperstown imprimatur.

As for the writers, we’ll leave them with their rank inconsistencies and their extra-large helpings of cognitive dissonance.

Update: Jeff Albert, who was a guest columnist and contributing writer to this site in 2006 and 2007, recently was hired by the St. Louis Cardinals as the organization's batting coach at Batavia (A) of the New York-Penn League. Here is an excerpt from the "Cardinals announce Minor League field staffs" press release:

Jeff Albert has been hired as hitting coach at Batavia. Albert played collegiate baseball at the Division 3 and Division 1 levels, with a couple of stops among independent professional teams. He began working on instruction and strength and conditioning with high school, college and professional players shortly thereafter and is owner and operator of swingtraining.net, which is a site dedicated to baseball training and analysis.

Best wishes to Jeff, who is weeks away from graduating with a Master's in Exercise Science at Louisiana Tech. He will report to the team's minor league spring training facility in Jupiter, Florida on March 1. Congratulations!

Late Add: Peter Gammons, who makes "no bones about (his) strong feelings about the human element," wrote a thoughtful piece about the exploration of cyberspace as it relates to politics and sports.

Pure numbers cannot do justice to character and drive and energy. They cannot measure the impact Robin Yount had on teamates when he ran down the first-base line at the same breakneck speed (one scout had nearly 90 Yount games in a six- or seven-year period and claimed he never got Yount faster than 3.9 seconds, or slower than 4.0). Mariano Rivera, Josh Beckett and David Wright are what they are because of who they are.Stat lines cannot quantify work habits, the ability to learn, emotional stability, etc., but they are important guidelines by which to remind us that, in the end, performance counts.

Gammons identifies Jack Morris, George Brett, David Ortiz, and Derek Jeter as examples of players who "transcended the human elements that so alter the sport." He adds, "But those are parts of a greater landscape of arguments." Peter admits that "we all know more about baseball because of the proliferation of creative thought" and lists The Baseball Analysts among approximately a dozen general baseball sites he enjoys, as well as another 15 team-specific sites "club officials read."

| Baseball Beat | January 17, 2008 |

How do you like your Rice? I'll take mine fried, thank you. Buster Olney, on the other hand, has a completely different recipe for his Rice.

With the above in mind, Olney responded today to my two-part retort to his posts about Jim Rice's Hall of Fame worthiness last Friday and Saturday.

• Rich Lederer strongly disagrees with what was written here in the Jim Rice HOF debate last week, in a couple of pieces you can locate through this link. It's interesting that he says he played APBA and counted the "on base numbers" on the card, an acknowledgement which, as a baseball board game nerd, I fully appreciate. In playing thousands of games of Strat-O-Matic Baseball, and drafting dozens of teams, the system I have always used to evaluate players before any draft (until this moment a closely guarded secret from my Strat-O rivals) was to add up the number of points based on the possible rolls of the dice. In other words, in the '80s, if Wade Boggs had hits against right-handers in Column 1 in slots 5 through 10 (I'm sorry, but anybody who hasn't played Strat-O is going to get lost in this part of the conversation), a walk or hit in Column 2-6, and hits or walks on Column 3-5 through 3-10, he scored 59 on that side of his playing card -- six points for every roll on a No. 7, five points for any roll of Nos. 6 or 8, four points for any roll of Nos. 5 or 9, three points for any roll of Nos. 4 or 10, two points for any roll of Nos. 3 or 11, and a point for a roll of Nos. 2 or 12.I'd go through all the cards and calculate these ratings of all pitchers and hitters versus right-handers and left-handers. This, of course, was a Strat-O-Matic version of calculating on-base percentage. I loaded up on guys who scored the highest in this system, including platoon monsters like Jeff Leonard and Al Newman (who killed lefties) and Dwayne Murphy (who drew tons of walks against right-handers on his '87 card), and I'd trade to get Boggs and Tim Raines; my teams always fared very well. In the early '80s, I drafted Gene Tenace as a backup catcher to pinch hit, because he drew walks, and I would effectively pair him with Ron LeFlore, who I'd keep as a fourth outfielder and as a pinch-runner because of LeFlore's high Triple-A stolen-base percentage. In a close game in the late innings, Tenace could come off the bench to draw a walk and LeFlore would swipe second, and I'd be in business.

But regardless of how Rich or I preferred to play our board games, the reality is that in the '70s and early '80s, many of the executives who ran teams and the managers who managed and the players who played did not value walks the way walks are valued these days. This is partly a function of how the game was played -- the strike zone was larger, there were fewer pitches per plate appearance, and there was more pressure on the hitter to swing the bat. The conventional wisdom was that a middle-of-the-order hitter who took a lot of walks was actually hurting his club (especially if he was a cleanup hitter on a team in a lineup without a lot of depth). Now, was that philosophy flawed, in part? Sure. Folks in baseball should've absorbed Bill James' Baseball Abstracts from the outset (I got my first as a high school graduation present in the spring of '82). But the bottom line is this: Rice's approach to hitting was engrained in the game; guys in the middle of the lineup focused on generating RBIs.

During Eddie Murray's batting practice sessions, he would take a round in which he focused on practiced emergency swings -- awkward hacks at pitches off the plate, or pitches on which he was fooled -- in order to put the ball in play. Why? Because he considered himself an RBI guy, and if there was a runner at third, his focus was to do everything he could to drive the run in. Despite breaking into the big leagues under a progressive manager like Earl Weaver, Murray wasn't thinking about on-base percentage; he defined himself by RBIs. He didn't say at the end of the year, Hey, I had an OBP of .380 and I feel damn good about that.

His first responsibility to the team, he felt (and according to colleague Peter Gammons, Rice had an approach similar to that of Murray), was being in the lineup every day as a reliable teammate, and in this role, he measured himself by RBIs -- more than 80 in 17 of the first 19 seasons of Murray's career. As Peter remembers, Rice felt enormous pressure to drive in runs, and this was not merely self-inflicted. With runners on first and second base and one out and the Red Sox down a run and the count 2-1, he was going to swing at a fastball on the outside corner with the intent of driving in the run.

Rich might not like it, and it might not make a lot of sense in today's OBP world, but that is the way sluggers were taught and expected to think. Ted Williams was one of the sluggers who took walks, refusing to swing at pitches out of the strike zone. Look at the year-to-year leaders and you can see that the elite players tend to walk and strike out more than they used to.

Football has some parallels. Johnny Unitas is regarded, in football history, as one of the greatest quarterbacks in history. And if you look at his completion percentages and quarterback ratings and interception rates, you could, at first glance, ask: What's the big deal? There were four quarterbacks who had higher ratings this year than Unitas did in his best season. His completion percentage would be pedestrian in the modern game, a skill that you might think would translate in a conversation about eras, in the same way that you might think that Rice should've drawn more walks.

But if you talk to anyone affiliated with the NFL in Unitas' era and what they will tell you, without hesitation, is that Unitas was The Man. The game was just different.

There was one thing that Rich wrote that really caught my eye, about past MVP Award results: "At the risk of speaking on behalf of serious fans and students of the game, I believe we would all like for the MVP voting to be a 'barometer' of Rice's [and everyone's] play. We're not 'ignoring the MVP voting entirely.' Instead, we're just discounting it."

I'm sorry, but I guess I'll never be such a serious fan or student of the game that I would discount the information generated in hundreds of MVP votes cast in 14 AL cities during Rice's time as a player. I'll never be such a serious student of the game that I would presume that the past voters like Peter Gammons, Ross Newhan, Tim Kurkjian, Tracy Ringolsby, Ken Rosenthal, Richard Justice, Gerry Fraley, Moss Klein, Bob Nightengale, Bob Elliott and others who spent 10-12 hours a day in ballparks eight months a year didn't know what they were watching. I'd never presume they were simply ignorant in giving Rice all those MVP votes he collected through the years.

And I've always assumed there is plenty of room for opinion and interpretation in the game. Rich's point of view is not wrong; it's his opinion. And I have my own.

Olney and I clearly disagree on Rice's value and place in baseball history. Even though we both own the 1982 Bill James Baseball Abstract, we also don't agree on how an offense functions.

As it relates to APBA and Strat-O-Matic, I never drafted or traded for Jim Rice in my ten-year stint in the Greater Los Angeles APBA Association. I just was never attracted to the fact that he was a below-average ("OF-1") or average ("OF-2") fielder, a below-average ("S") or average baserunner (neither "S" or "F"), rarely walked (averaged 2 "14"s on his card), didn't steal bases (never had an "11" and rarely had a "10"), and grounded into lots of double plays ("24"s). His strengths were limited to the fact that he had three or four "power numbers" ("0-6") on his card and normally had a couple of "7"s (which generally resulted in singles against most pitchers).

Just like in "real" baseball, Rice was a low on-base, high-slugging type hitter. Yes, he could drive in runs but wasn't adept at creating as many runs as the best players. I was much more attracted to players who could hit for power and get on base. Walks were valuable back then. It didn't matter if one was managing an APBA or major league team.

In Rice's rookie year, the Cincinnati Reds led the major leagues in walks and won the World Series (ironically beating the Red Sox in seven games). The Reds also led the majors in BB the following year while winning the World Series once again. Throughout baseball history, teams that have ranked at or near the top in drawing or preventing walks have won much more often than they have lost. For offenses, getting on base is of paramount importance – it always has been and always will. For defenses, keeping runners off base is basically what it has been, is, and will always be about. It's just a simple truism.

As it relates to my APBA playing days, I traded for two of Rice's fellow outfielders – Dwight Evans and Fred Lynn – yet never even thought about acquiring him. Like in "real" baseball, he was a good hitter but was limited in all other phases of the game. Evans and Lynn also hit well but got on-base more often via walks and were significantly better defensive players. In my mind, Rice was basically the equal of George Foster – and I never traded for him either. However, I owned Dave Parker during his peak years because he was a better hitter, better baserunner, and a better fielder than Rice.

Following the 1981 season, I made sure to trade for the number one draft pick and took Tim Raines even though many other league members were partial toward Fernando Valenzuela. Raines was one of the very best players in the game. He got on base frequently, stole bases often and at a record clip, and was as valuable at scoring runs as the Rices and Fosters were in driving them in. I knew what was important back then, and I know what is important today.

With respect to the Johnny Unitas example offered by Olney, I think he is missing the point. Johnny U. was outstanding in his day and remains one of the top QBs in the history of football despite the fact that present-day passers have surpassed his records. Relative to his era, Unitas was fantastic. Nothing will ever change that. The fact that his "completion percentage would be pedestrian in the modern game" has zero impact on his status as one of the all-time greats of the game.

I respect many of the writers Olney mentioned, and I value their opinions. It's not a matter of whose viewpoints carry more weight as much as it is about understanding and appreciating what wins and loses games. Just as no one stat is says it all, no one person or groups of persons knows it all. Beat writers, baseball columnists, statisticians, analysts, scouts, players, managers, coaches, umpires, general managers, owners, fans . . . all of us have a perspective that is neither better nor worse than the others based on our employment alone.

My Dad was a sportswriter who covered the Los Angeles Dodgers from 1958-1968. He never missed a game in 11 years. As such, he probably saw more games than any other beat writer during those years. A member of the Baseball Writers Association of America, he voted for MVP and Cy Young Awards in his day. He also voted for the Hall of Fame up until his death in 1978. Dad was also the statistician for the Dodgers, maintaining game logs, home and road, left- and right-handed splits, etc. well before doing so became popular.

A little bit of my Dad rubbed off on me. I grew up going to games at the Coliseum and Dodger Stadium, and playing Little League, Pony League, Colt League, Connie Mack, American Legion, and high school baseball. I played fast-pitch softball for 10 years. I played APBA during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. I have been a participant in one of the longest-running fantasy leagues for more than 25 years. I coached my son's Little League team. I have attended dozens of games every year of my adulthood and have subscribed to MLB Extra Innings since 2001. Heck, I've even dabbled as a writer and analyst for the past five years.

I own all 12 of the Bill James Baseball Abstracts, and have read every book from cover to cover. I'm not an expert, but I pride myself on having an open mind when it comes to learning more about this great game. I can only hope that those who have been given the privilege of voting for MVPs, Cy Youngs, and Hall of Famers will be equally open minded when it comes time to fill out their ballots.

[Additional reader comments at Baseball Primer Newsblog.]

| Change-Up | January 16, 2008 |

In each baseball game, both teams field players at the same positions. Other sports feature more interchangeability between the various players on the playing surface. Magic Johnson won the NBA Finals MVP as a rookie when he subbed for Kareem Abdul-Jabbar at center to clinch the title. Magic's big enough and tall enough to do that. While there will always be valuable guys like Chone Figgins playing baseball, needless to say, Jason Varitek could not have replaced a slumping Julio Lugo in the World Series.

This phenomenon engenders a situation in which, for the purposes of team construction theory, baseball contests end up amounting to a series of indirect, one on one match-ups. Let's stick with the Red Sox. Varitek was just ok by his standards in 2007 (.255/.367/.421) but he was good enough that on a given night, chances were the Red Sox had the better catcher than the other team. The same could be said of Kevin Youkilis, Dustin Pedroia, Mike Lowell and Manny Ramirez. None of these players is the best at their given position but more likely than not, better than the guy in the other dugout penciled into the lineup at the same position. Have the upper hand at enough positions, mix in solid pitching and you are in business.