| Designated Hitter | June 13, 2011 |

The recent death of Harmon Killebrew prompted many touching reminiscences about a man with seemingly no enemies, despite carrying around the nickname of “Killer” for most of his life. (He did not really need a nickname; both his first and last names are unique in major league history.) By all accounts, he was a gentle and loving person, who also happened to hit home runs more frequently than anyone of his time. He hit 45 or more round trippers six times in the 1960s, while no other American League batter did it more than once. For baseball fans of a certain age, no player will ever better personify the word “slugger.”

Another interesting thing about Killebrew, perhaps unique among Hall of Fame players: he was repeatedly shifted between three defensive positions throughout his career, getting 44% of his starts at first base, 33% at third base, and 22% in left field. While many players shift positions along the defensive spectrum as they age, moving from shortstop to third base, or from left field to first base, Killebrew’s managers shifted their star hitter, nearly to the end of his career, depending mainly on the other players on the team. (It would be as if Tony LaRussa started playing Albert Pujols at third base. Oh, wait …)

Let’s review:

1954-58. Forced to start his big-league career early because of the bonus rule, Killebrew spent parts of five seasons as a little-used infielder for the Washington Senators.

1959. Having traded Eddie Yost, manager Cookie Lavagetto gave Killebrew the third base job. Harmon responded with a league-leading 42 home runs, and started his first All-Star game.

1960. Harmon remained at third until mid-season, when Lavagetto decided he needed to get Reno Bertoia into the lineup (or Julio Becquer out of it) and shifted Killebrew across the diamond to first base.

1961. With the franchise now in Minnesota, Killebrew spent the first half of the 1961 season splitting time between first and third, until Sam Mele became the skipper in mid-season and kept Killebrew at first. (I am not going to recite lots of offensive statistics, so just go ahead and assume that Killebrew hit 45 home runs and batted .260 with a bunch of walks, since he did that every year.)

1962. Just prior to the start of the 1962 season, the Twins acquired Vic Power, a great defensive first baseman, and moved Killebrew to left field for the first time.

1963. Left field.

1964. Left field. Tony Oliva took over in right field in 1964, and Power was discarded early in the season, creating a perfect opportunity to get Killebrew back to first base. Instead Mele shifted Bob Allison and left Killebrew in the outfield.

1965. Killebrew moved to first base (and Allison to left), but Harmon began shifting to third often by mid-season so that the team could play Don Mincher against right-handed pitchers. In early August Killebrew hurt his arm during a collision (while playing first base), but returned in September and played all seven games—at third—in the World Series.

1966. He played all 162 games, moving between third base, first base, and left field depending on who else Mele wanted to play. The Twins also had Cesar Tovar playing all over the field, leaving Mele about seven million possible defensive alignments. Tovar played this role for several years.

1967. Mincher was traded to the Angels, allowing Killebrew to play a full season at first base (160 games) for the first time in his career.

1968. A full-time first baseman again, Killebrew ruptured his hamstring in the All-Star game stretching for a throw on Houston’s AstroTurf (which was blamed at the time for the injury). When he returned in September Rich Reese had taken over at first, so manager Cal Ermer put Harmon (recovering from a severe injury) back at third base to play out the season.

1969. New manager Billy Martin took one look at the 33-year-old slugger coming off major surgery, and decided to return Killebrew to the 3B-1B role, allowing Martin options at the other corner spot. Harmon started all 162 games (96 at third base, 66 at first), drove in 140 runs, and won the MVP award, while the Twins nabbed the inaugural AL West title.

1970. Martin was replaced as skipper by Bill Rigney, who made Reese more of a full-time player. Killebrew started 129 games at third, but still managed 26 back at first.

1971. Killebrew again played both corner spots, though Reese’s poor season (.219) gave Killebrew several long stretches at first, where he started 82 times.

1972. For the first time since 1958 (when he played just nine games in the field), Killebrew played just one defensive position, first base. He was 36 and had slowed down quite a bit, though he could still rake (138 OPS+).

1973-75. With the advent of the designated hitter, the elderly Killebrew seemed to have a ready-made role. Unfortunately, the Twins also had a hobbled Tony Oliva, who needed the role even more. Killebrew eventually made it to DH, but spent his final three seasons fighting injuries and ineffectiveness.

OK, so the question is: how much defensive value did Harmon Killebrew have? According to bWAR, Killebrew’s cumulative defensive value was -7.6 wins, meaning that his place on the field cost his teams nearly 8 games on defense when compared with a replacement level player. Killebrew was a big guy, not fast, and no one ever accused him of being a good glove man. On the other hand, one wonders whether he could have been better on defense had he been allowed to play one position (preferably first base) for 15 years.

More importantly, did Killebrew’s ability to play multiple positions, often day-to-day, provide additional value to his team? In 1969 Martin played Harmon at third base 2/3 of the time so that Rich Reese could play first base. In an otherwise undistinguished career, Reese hit .322 with 18 home runs (good for a 139 OPS+), Killebrew had his best year, and the Twins led the league in runs. According to bWAR, Harmon’s (mostly) third base play cost the team 1.3 games on defense. This might be true, and Harmon’s isolated value might have been better had he just played first base all season and let Frank Quillici or someone play third. In order to get Reese’s bat in the lineup (or Mincher’s, Power’s, or Bertoia’s), Killebrew was asked to play a position he could not play particularly well.

It seems to me that Killebrew’s “value” to the Twins might have been greater than his statistical record might show.

Another player shifted around the diamond throughout his career was Pete Rose. Unlike Killebrew, Rose did not move day-to-day—he stayed in one place for several years before moving on. Also unlike Killebrew, Rose was an outstanding defensive player for part of his career, before being asked to move again. Rose came up as a second baseman in 1963, then moved to left field (1967), right field (1968), left field (1972), third base (1975), and first base (1979). Let’s examine his move to third base.

Rose won two Gold Gloves in right field, where he had good range though only a fair arm. He was moved to left field in 1972 largely in deference to Cesar Geronimo, a great defensive player with a cannon. In left field, Rose was outstanding. How outstanding? According to the defensive runs metric used on baseball-reference.com, here are the best outfielders in baseball over the years 1972-74, in aggregate.

Pete Rose 52

Paul Blair 52

Cesar Geronimo 34

Bill North 30

Bobby Bonds 26

Other than Rose, these are all center fielders. As a hitter, Rose trailed only Willie Stargell, Cesar Cedeno and Reggie Jackson in batting runs among outfielders, making him every bit as valuable as he was famous.

Nonetheless, in May 1975 Sparky Anderson moved Rose to third base. The effect on the Reds was to replace third baseman John Vukovich, hitting .211 with zero home runs, with left fielder George Foster, who would hit .300 with 23 home runs. Rose continued to hit as well as ever, and the team won 108 games and the World Series.

Over the 1975 and 1976 seasons combined, Rose had the sixth highest total of batting runs in the major leagues, but rather than being worth two wins per season on defense (as he had been in left field) he was now worse than replacement level. Meanwhile, George Foster became a star and the Reds won two championships. Anderson could have moved Foster to third base, but he thought Rose could handle it. Given what happened to the Reds, I am forced to conclude that Anderson knew what he was talking about.

So, what am I saying? I am not saying that there should a new statistic to measure flexibility, nor am I suggesting that the WAR values we have become familiar with are wrong, or should be adjusted. I am saying: assessing “value” is complicated.

Mark Armour is a baseball writer living in Corvallis, Oregon, and the director of SABR’s Baseball Biography Project. His book Joe Cronin: A Life in Baseball was published in 2010 by the University of Nebraska Press. He and Dan Levitt are working on a sequel to their 2003 book Paths to Glory.

| Baseball Beat | June 09, 2011 |

The Los Angeles Angels drafted Matt Scioscia, the son of manager Mike Scioscia, in the 45th round of the 2011 First-Year Player Draft on Wednesday. The younger Scioscia, listed in the press release as a 6-2/220 catcher from Notre Dame, was the 1,365th pick overall.

Scioscia started six times and played in a total of 16 games in his senior season. He went 6-for-30 with no extra-base hits and no walks. It appears as if Scioscia did not play in the field as he had no putouts, assists, or errors. Over his four-year career at Notre Dame, Matt hit .267/.323/.335 in 88 games and 195 plate appearances.

The Angels also drafted Scioscia out of Crespi Carmelite HS (Encino, CA) in the 41st round in 2007, but he opted to attend college. His bio on the Fighting Irish website claims he "would have been drafted much higher if not for his strong commitment to Notre Dame." Perhaps. But it's important to note that he wasn't selected after his junior season last year and has only been taken by the Angels twice and no other team in three separate drafts.

The father expects his son to sign with the Angels today. "He's excited just for the fact to get out there and play professional baseball. He's going to work hard on the defensive side. He can swing the bat. He is definitely excited for the opportunity."

I wonder how many college players with just six hits all season were drafted this year?

Nonetheless, there's hope for Matt, Mike, and the Angels. After all, Mike Piazza was selected by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 62nd round of the 1988 draft, apparently as a favor to his godfather, who was none other than manager Tommy Lasorda. Piazza was the National League Rookie of the Year five years later en route to becoming the best-hitting catcher of all time in a Hall of Fame career that produced a .308 AVG/.377 OBP/.545 SLG, including 2,127 hits, 427 home runs, and 1,335 RBI.

| Baseball Beat | June 08, 2011 |

clutch

–adjective

1. Being or occurring in a tense or critical situation: won the championship by sinking a clutch putt.

2. Tending to be successful in tense or critical situations: The coach relied on her clutch pitcher.

My friend Jeff Wimbish called yesterday late afternoon while both of us were driving home from our respective offices, rhetorically asking me if Placido Polanco was "clutch." Jeff was listening to the Dodgers-Phillies game and L.A. play-by-play radio broadcaster Charlie Steiner said, "Polanco has always been a great clutch hitter."

Off the cuff, I told Jeff, "I doubt it." I proceeded to say that Polanco was the type who announcers love to call a "professional hitter." How does one become a professional hitter, you ask? That's simple. You have to be a (1) veteran, (2) make good contact, and (3) hit for a high average. As it relates to Polanco, he is 35 years old. Check. Secondly, he has struck out in only 6.6% of his plate appearances over the course of his career (vs. a league average of 17.1%). Check. Lastly, he has a lifetime average of .303. Check mate.

Circling back to the question at hand, I concluded that Steiner would have served his listening audience better had he backed up his claim that Polanco was clutch. Thanks to all the public resources available to us, I was able to check Polanco's splits to determine if he was indeed clutch when I returned home. I'm not sure how one qualifies, but I suspect Polanco doesn't quite make the grade. I put together the following table to satisfy my curiosity.

| AVG | OBP | SLG | OPS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career | .303 | .348 | .411 | .758 |

| Men On | .315 | .358 | .409 | .767 |

| RISP | .307 | .354 | .405 | .758 |

| 2 Outs, RISP | .263 | .328 | .350 | .678 |

| Late & Close | .283 | .340 | .382 | .722 |

| Tie Game | .300 | .344 | .401 | .745 |

| Within One Run | .303 | .350 | .414 | .763 |

| High Leverage | .305 | .347 | .399 | .746 |

| Low Leverage | .301 | .342 | .417 | .759 |

| Innings 7-9 | .287 | .336 | .383 | .720 |

Oh... Polanco went 0-for-3 with a BB and an RBI. In the bottom of the first inning, no score, and a runner on second base with nobody out, he grounded into a fielder's choice (1-5). In the home half of the second, the Dodgers up 1-0, bases loaded with two outs, he walked on four pitches and was credited with an RBI. In the fourth, the Dodgers leading 4-1, nobody on with two outs, he lined out to third. In the seventh, the Dodgers still on top 4-1, a runner on first with one out, he flied out to right. It was Polanco's final at-bat of the game as he was on-deck when Shane Victorino flied out to center to end the contest. The Dodgers beat the Phillies, 6-2.

The outcome may have turned out differently if only there had been a clutch opportunity or two for Polanco.

| F/X Visualizations | June 06, 2011 |

Jose Bautista’s breakout has been one of baseball’s most interesting stories of the past two years. From 2006 to 2009 Bautista was a slightly below-average hitter for the Pittsburgh Pirates and Toronto Blue Jays, hitting between 13 and 16 home runs each year. But since the start of 2010 Bautista has hit more HRs, 74, than anyone else in the majors — Albert Pujols is second with 55. Over that time he also leads the league in walks taken with 152 and walks per plate appearance, 16.6%. All those walks and home runs make Bautista the best hitter, as measured by wOBA, since the start of 2010. Here I am going to look deeper into Bautista’s success.

Bautista is a pronounced pull-HR hitters. Of his 74 HRs since the start of 2010 just three have gone to the opposite field (that is had a horizontal angle of less than 90° according HitTracker). That is fewer opposite-field HRs than any other player on the 2010-2011 top 10 HR list — even though he tops the list.

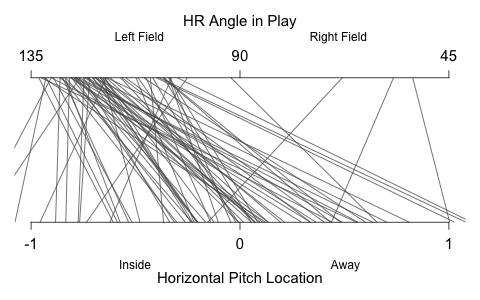

With this extreme pull power one would assume he couldn’t handle away pitches as well. Pitchers have assumed as much, Garik16 showed that pitchers have incredibly pitched him away. But he also showed that Bautista has gotten better over the past three years at dealing with those outside pitches, and now has a positive run value on them. Here is a big reason why. This graph shows the horizontal pitch location on each pitch Bautista has hit for a HR since the start of 2010, and then the angle of that HR in play.

A large number of Bautista’s HRs have come off pitches on the outer half of the plate, and he has still been able to pull those pitches to left field. In fact he has three pulled HRs on pithes far off the plate away. (On a side note Max Marchi has a great article analyzing this type of data at the Hardball Times.)

With that prodigious power pitchers have responded by increasingly pitching around Bautista. He has eight IBBs so far this year second in baseball to Miguel Cabrera’s 12. And even when he is not intentionally walked he is not given much to hit; he sees the fewer pitches in the zone than any other hitter.

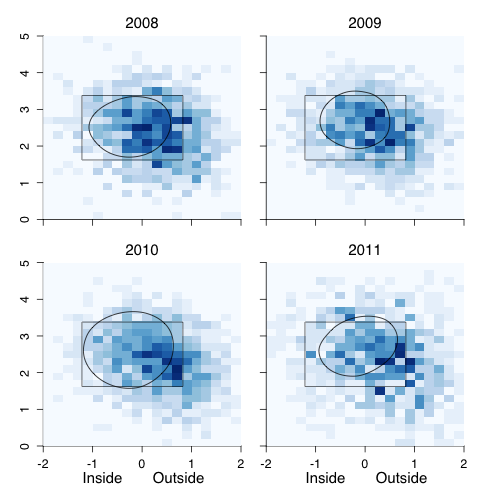

Here is a set of graphs showing the how often Bautista sees pitches in each location, based on the intensity of the blue, and Bautista’s 50% swing contour. So Bautista was more likely than not to swing at a pitch within the contour, and more likely than not to take a pitch outside it.

In 2008 and 2009 pitchers pitched to Jose Bautista as they would to most average hitters: throwing mostly in the zone and slightly away. With Bautista’s breakout starting in the end of 2009 and continuing in 2010, pitchers increasingly threw away and down. This change in location is partially a consequence of Bautista seeing fewer fastballs and more breaking and off-speed pitches. Bautista’s swing zone has remained fairly static, and as a result he is walking much more.

Around the end of April Dave Cameron suggested that Jose Bautista might be the best hitter in the AL. Since then Bautista has continued to hit like crazy, and his ZIPS rest of the season projected wOBA is now the best in baseball: an amazing ascent for a batter who went into the 2010 as an at-best average hitter.