| Touching Bases | January 28, 2010 |

Tim Lincecum retired 89% of batters he got to 0-2 or 1-2 counts. They had no chance. Here's how Lincecum's pitch selection breaks down on 0-2 and 1-2 counts, and the results of each pitch type.

| FB | CH | SL | CB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usage | 43% | 31% | 20% | 6% |

| Ball | 36% | 36% | 39% | 31% |

| Out | 32% | 43% | 46% | 51% |

| Hit | 7% | 4% | 4% | 1% |

| RV100 | 0.3 | -4.6 | -5.4 | -7.8 |

I'm grouping his four-seam and two-seam fastball. When I split the two, I find his two-seamer is much more effective than his four-seamer, but still not even as valuable as his off-speed offerings. I mean his changeup and slider are true out pitches. In fact, his change might be the best out pitch in baseball. You probably already know that. Yet his fastball on these counts is merely average. Would he be better off sacrificing some of the effectiveness from his changeup in exchange for some added effectivenss on his fastball? Theoretically, yes, this would be the right move, and theoretically, he could do this by throwing his changeup so often that batters come to expect it, and at the same time throwing his fastball so rarely that it acts like an out pitch, in that batters are fooled by it.

Yet for some reason, whenever I look at a pitcher's different pitch type run values, I notice disparities. Check out the A's duo of Brett Anderson and Mike Wuertz, who possibly possess the two best sliders in the game. Apparently, their fastballs suffer in spite of their extraordinary sliders. My guess is that they use their sliders as out pitches, so I wanted to see if there's a trend among pitchers to have a disparity in value between their out pitch and their fastballs. This type of analysis could, and probably should, be done for all counts, but I've been intrigued by the theory of the out pitch, so I'm limiting my sample to only pitches on 0-2 and 1-2 counts.

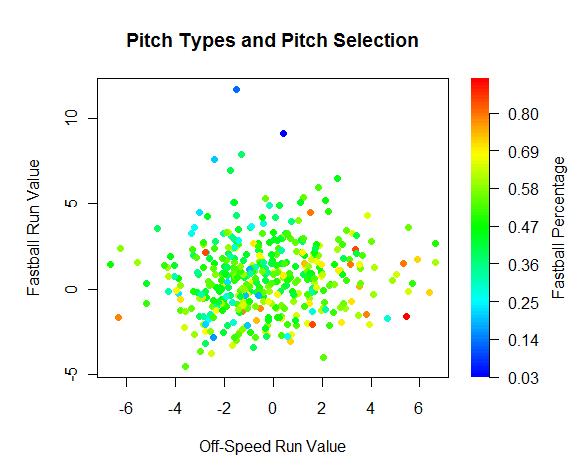

For the sake of simplicity, I'm grouping all fastballs together (four-seam, two-seam, cutter), and all off-speed pitches together (curve, slider, change, splitter, knuckler). So, in the following plot each pitcher represents a data point (minimum 200 pitches, Mo excluded), and the color of each dot represents how often a pitcher throws his fastball.

There appears to be a slightly positive trend line heading in the direction we would expect. Pitchers who extract value from one pitch type tend to get some value out of their other pitch types. Also, I see more yellow and red points on the right side and more blue points on the left side, meaning pitchers who throw more off-speed pitches have had better success with them than pitchers who throw fewer off-speed pitches.

Given that the average run value is defined as zero, 59% of pitchers perform at an above average rate with their off-speed offerings, while only 38% are above average with their fastballs. There are two and a half times more pitchers who have above average off-speed pitches and below average fastballs than pitchers who have below average off-speed pitches and above average fastballs.

As for correlation coefficients, which are on a scale of -1 to 1 with 1 representing a strong positive relationship, -1 representing a strong negative relationship, and 0 representing little or no correlation, I found that there is a weak correlation of .09 between fastball and off-speed run values. In addition, there is a correlation of -.25 between pitch type run value and pitch type frequency. Again, all of these data suggest that pitchers are not throwing their best pitches often enough in out pitch situations.

Returning to the above graph, one interesting note I made is that the two bluest points also show up as the two highest points on the graph. This means that the two pitchers who have the lowest fastball percentage have also had the poorest fastball results. Want to take a guess at the names behind the data points?

Well, it turns out knuckleballers should stick to the knuckleball. R.A. Dickey and Tim Wakefield aren't fooling anybody by trying to sneak a fastball in there. Wake's thrown 34 fastballs in 0-2/1-2 counts, and he's generated nine outs compared to six hits. That's abysmal. Dickey is just as bad, with 14 outs against nine hits. They're doing batters a favor by throwing fastballs.

There seems to be a stigma to pitching backwards, but if your out pitch is your best pitch, and you can throw it for strikes and it doesn't add stress on your arm, then you should consider turning your fastball into a secondary pitch, making it a potential out pitch as well

Pitch type run values don't tell the whole story. It's important to look at what happens in the entire at-bat, not just the one pitch. For example, it's possible that pitchers are throwing fastballs outside the strike zone to set up breaking balls as their out pitch. So they're intentionally lowering the value of their fastballs, and therefore are getting better overall results when they throw the fastball even though the fastball doesn't get the glory in the run value column. However, the conclusions I found when looking at the linear weights value of the entire at bat remain the same as when I analyzed single pitch run values.

I'm including a scatter plot of the categories I've used--fastball/off-speed percentage, fastball/off-speed run value, and fastball/off-speed linear weights-the overall linear weights value of the at-bat following the 0-2/1-2 fastball/off-speed pitch). Use the scroll bar on the bottom right to locate your pitcher of interest.

| Change-Up | January 27, 2010 |

To the extent that you want more solid MLB-caliber players than not on the roster, the addition of Xavier Nady is a nice get for the 2010 Cubs. Short money, decent enough right-handed bat, positional flexibility, in some ways the move was a no-brainer. Almost any team in baseball would improve, some more than others, as a result of having Nady on their roster.

The problem for the Cubs, and any other team for that matter, is that resources and roster spots are finite. Coming off of 83 wins playing in one of baseball's weakest divisions, a few focused, tactical moves could have resulted in enough wins added to spring the North Siders into contention. As it stands at the end of the Hot Stove season, their starting rotation looks thin and injury prone while their offense looks to be improved. On the whole, it looks like this Cubs team should be just a bit better than last year's club. With luck, they'll contend. With Xavier Nady in the fold, they'll still need luck.

It's hard not to think back to the Milton Bradley episode and how much it distracted Chicago when looking at their moves this off-season. Losing Bradley and picking up Carlos Silva and Marlon Byrd, wherever you come down on the argument that they just had to part ways with Bradley, amounts to wheel-spinning. Byrd is no better than Bradley, Silva is just awful. Nady might hit southpaws better than Kosuke Fukudome, but how much of that differential offensively does Nady give back when he takes the field in right? As I see it, the most enticing part of this addition is that it protects against further Soriano deterioration. That's no small thing, but in an off-season where just a few shrewd moves could have made all that difference, Bradley, Byrd, Silva, Nady - the Cubs just haven't seem focused.

With the ownership commotion surrounding the club and Soriano's bi-weekly direct deposit hamstringing baseball operations, I can empathize. But at the same time, this was an off-season that called for even greater focus. There wasn't going to be a lot of money to spend, but the Cubs had a roster on the cusp. And it still is on the cusp, so it's not like they've mismanaged their way out of any hope for 2010. They just could have done more, and the announcement of the Nady signing tells me that they're not thinking strategically enough. Nady just won't make much of an impact, when there was impact at a great price still to be had on the free agent market.

You want to go short money and improve the club? Well what about Orlando Hudson or Felipe Lopez for a team whose second basemen hit .254/.310/.357 in 2009? If the Cubs opted to bolster their starting pitching instead, to avoid relying on some combination of Tom Gorzelanny and Randy Wells and Sean Marshall for 400 innings, then Jon Garland and his 200 league average innings could have helped. Garland would have led the 2009 Cubs in innings pitched. And heavens, Johnny Damon is still sitting out there. Maybe you don't want to hurt Alfonso Soriano's feelings or you otherwise sense a logjam in the outfield, but Damon is still an excellent player whose value seems to have plummeted without good reason.

Again, I want to stress that I can't get too worked up about any of the Cubs moves this off-season. I understand the chemistry stuff and the case for why Bradley had to go. Center field was a hole that Marlon Byrd should be able to fill. Xavier Nady adds some depth and a nice platoon partner if deployed appropriately. But if the Cubs looked at their roster and determined they only had a few moves to make this off-season, I wish they would have been executed with more focus and precision. Because a couple wins could mean all the difference in the National League Central.

| Behind the Scoreboard | January 26, 2010 |

This week's subject is a little lighter fare, focusing on how the stolen base has changed through time, and whether there is any rhyme or reason to why that has occurred. The amount of stolen bases has fluctuated throughout history. The early days of baseball saw a lot steals until the live-ball era began. As teams started scoring more and hitting more home runs, the speed game went on the decline, picking up again as scoring decreased throughout the 1980's.

A major explanation for the difference in stolen base strategies is that teams were rationally reacting to run environments. As scoring became harder, teams played "small ball" in order to scratch out runs. The goal here is to find out if teams actually did this and whether it was a rational strategy.

First, the relationship between runs and stolen bases. One would think that stolen bases would increase as run scoring decreased. Is this the case? According the above scatter plot, we see a very tenuous relationship. The points out to the right are deadball era years, where stolen bases are high. However, contrary to popular perception run scoring wasn't all that low during the deadball years. The relationship isn't any stronger after 1920 either - the rest of the scatter points are basically in a big clump. That pretty much puts to rest the myth that stolen base trends are a reaction to run scoring.

But is there another relationship between offense and stolen bases? Indeed, the graph above shows the relationship between steals and home runs over time. As you can see, steals and homers seem to be inversely related. Meanwhile, it doesn't have much of a relationship with scoring. A scatter plot doesn't tell quite as strong of a picture, although it's very easy to identify various eras based on these two statistics, which is something that I found pretty cool, even though it wasn't the point of the study.

It would make sense that teams would limit their steals when run scoring was high, but it might make even more sense when those runs are coming via the longball. Obviously, there's no point in taking an extra base if you're likely to be knocked in with a homerun anyway.

The real test of looking at the value of the stolen base is the break-even point. How often must a stolen base attempt be successful, before it is a good play? And how did this breakeven point change over time? Using Tom Tango's Run Expectancy Generator (which didn't do a perfect job across eras mainly because of differing error rates, but it's close enough) I calculated the break-even points on a no-out steal of second base. Obviously there are other situations in which a steal takes place, but being a common one, it's reasonable to use this as a baseline for how advantageous the stolen base is across eras. Picking the most typical point in each of the eras above, and tossing in anomalies 1968, 1930, and today, we can see that while the breakeven point has changed some, there's not a huge difference.

1905: 74.0%

1923: 80.3%

1930: 81.8%

1937: 80.5%

1959: 79.3%

1968: 75.2%

1985: 79.3%

2001: 81.1%

2009: 81.0%

Obviously looking at the break-even rates, we would expect that the number of steals would be highest in the dead-ball era and in 1968. While steals were higher in the dead-ball era, the number of stolen bases in the 1960's was eclipsed by the 1980's and even the current era, which has much higher scoring. While stealing was a better proposition in the 60's, it was used as much as it is today.

Of course, there is a final factor that comes into play: the likelihood that a stolen base attempt is successful. I can't think of much good reason for why the stolen base success rate would change over time, but the fact is that it has changed dramatically. Modern base stealers are vastly more successful than they have been in the past. Why this is, I'm not sure. Perhaps players are faster now, without a corresponding increase in catcher arm strength and accuracy. Perhaps teams are better at reading and timing pitchers' moves to the plate. Or perhaps teams are just better about stealing bases they know they can make. In any case, the chart below combines the data.

As you can see, the stolen base success rate varied tremendously over time. The variation here is far more than the variation in the break-even rate. Hence it would make sense that teams would steal more bases today than in the past. Certainly there is more stealing in the modern 1974-2009 era, than there was between 1930-1973. However, the odd scenario is the deadball era and the 1920's, where stealing was still prevalent, despite abysmal success rates. In the 1920's stealing was about as lucrative as it is today, but with about a 55% success rate vs. a 73% success rate. Nevertheless, stealing was a common tactic.

Looking at the data as a whole, there's not a lot of rhyme or reason about why some eras are high stolen base eras and others are not. The rate of stolen base tends to go up and down without any real correlation between rate of success or strategic value. Part of the problem seems to come from the fact that homeruns seem to be the biggest determinant of whether teams steal or not.

However, home runs don't have a major impact on the breakeven rate. Using today's data, I kept the number of runs constant but doubled the number of homers. The breakeven point went up, but slightly (from 81.0 to 82.9). Similarly I brought the number of home runs down to zero (keeping scoring constant), and the breakeven point again changed very slightly (from 81.0 to 80.5). With the breakeven point barely moving despite dramatic differences in homerun rate, using homers or lack of homers to justify base-stealing strategy isn't a good move. However, I have a feeling that if home runs dropped precipitously today, teams would begin to employ vastly more basestealing - likely an irrational move. More important to a team's strategy is the run-scoring environment, no matter how the runs are scored.

In conclusion, baseball teams have behaved irrationally with their base-stealing strategies through history. It seems that steals have been a function of homers, or simply fashion, and not based on the actual value of the steal. But did you really expect John McGraw to have read the Hidden Game of Baseball?

| Baseball Beat | January 25, 2010 |

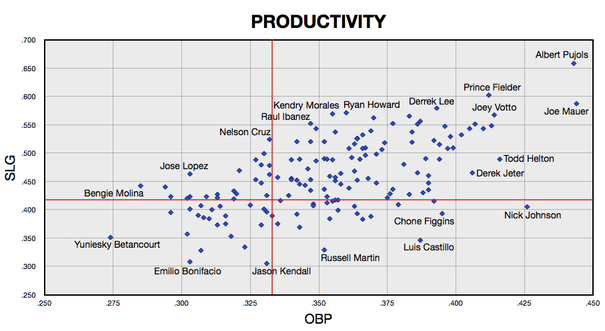

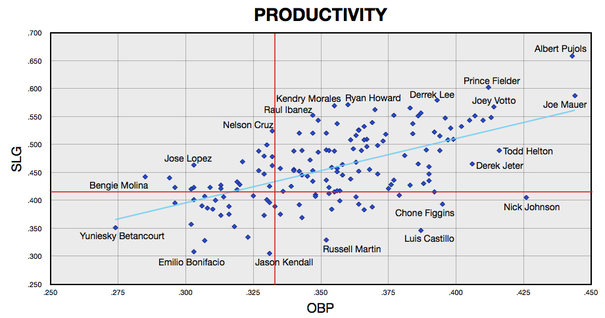

I introduced Graphing the Hitters earlier this month. The focus was on Productivity, defined as OBP and SLG.

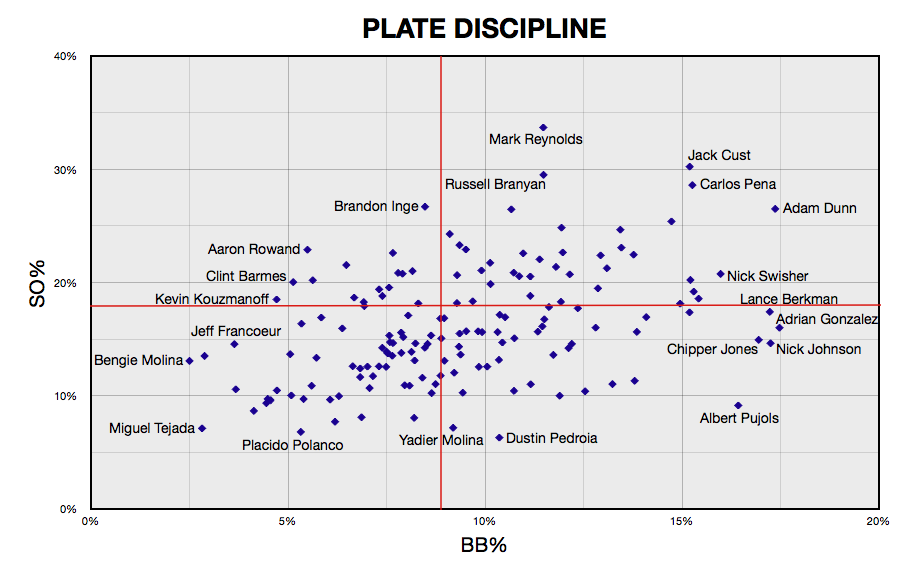

In this week's edition of Graphing the Hitters, I'm going to concentrate on Plate Discipline. The graph below plots walk rate (BB/PA) on the x-axis and strikeout rate (SO/PA) on the y-axis for every qualified batter in 2009. The intersection of the MLB averages for BB% (8.88%) and SO% (17.96%) created quadrants that classify players as better-than-average in both (lower right), worse-than-average in both (upper left), or better-than-average in one and worse-than-average in the other (lower left and upper right).

Unlike Fangraphs, I believe the denominator for strikeout percentage should be plate appearances (rather than at-bats). For whatever reason, Fangraphs defines walk percentage as BB/PA but strikeout percentage as SO/AB. As a result, while the raw numbers were downloaded from Fangraphs, the BB% and SO% were calculated separately.

Note: You can download a spreadsheet containing the PA, BB, SO, BB%, and SO% of the 155 hitters here. This information can also be used to locate the 134 players not labeled in the graph below.

My first question following the Productivity graph was "Is Albert Pujols any good?" Well, after looking at the Plate Discipline graph, I've got to ask the same question once again. This time around, I'm going to shout out my question.

OK, I think I've made my point now. Not that it was really necessary. Everybody already knows that Pujols is better than good. I mean, this guy is great. In fact, he is on pace to become one of the greatest hitters of all time and perhaps the best or second-best righthanded hitter ever.

Pujols has played nine seasons in the major leagues. He has ranked in the top ten in batting average, slugging average, on-base plus slugging, total bases, and times on base every year. What is less known is that Albert has improved his walk rate every single season while reducing his strikeout rate by a third since his rookie campaign in 2001.

In 2009, Pujols had the sixth-highest BB% (16.43%) and the ninth-lowest SO% (9.14%). That is a remarkable combination. He was the only player in the top 50 in walk rate with a strikeout rate below 10.0%. You have to go all the way down to No. 57 in the walk rankings to find someone with a lower strikeout percentage (Dustin Pedroia). The Red Sox second baseman had the lowest SO% (6.30%) in the majors.

Pujols and Pedroia are two of only 13 qualified hitters with more walks than strikeouts.

| First | Last | Team | PA | BB | SO | BB/PA | SO/PA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adrian | Gonzalez | Padres | 681 | 119 | 109 | 17.47% | 16.01% |

| Nick | Johnson | - - - | 574 | 99 | 84 | 17.25% | 14.63% |

| Chipper | Jones | Braves | 596 | 101 | 89 | 16.95% | 14.93% |

| Albert | Pujols | Cardinals | 700 | 115 | 64 | 16.43% | 9.14% |

| Todd | Helton | Rockies | 645 | 89 | 73 | 13.80% | 11.32% |

| Marco | Scutaro | Blue Jays | 680 | 90 | 75 | 13.24% | 11.03% |

| Joe | Mauer | Twins | 606 | 76 | 63 | 12.54% | 10.40% |

| Luis | Castillo | Mets | 580 | 69 | 58 | 11.90% | 10.00% |

| Victor | Martinez | - - - | 672 | 75 | 74 | 11.16% | 11.01% |

| James | Loney | Dodgers | 652 | 70 | 68 | 10.74% | 10.43% |

| Dustin | Pedroia | Red Sox | 714 | 74 | 45 | 10.36% | 6.30% |

| Yadier | Molina | Cardinals | 544 | 50 | 39 | 9.19% | 7.17% |

| Alberto | Callaspo | Royals | 634 | 52 | 51 | 8.20% | 8.04% |

Adrian Gonzalez led MLB in walk rate and walks (119) last year. He was one of five first basemen with more walks than strikeouts. Three second basemen, three catchers, one shortstop, and one third baseman also accomplished this feat, including three projected starters for the Boston Red Sox in 2010 (Marco Scutaro, Victor Martinez, and Pedroia). The St. Louis Cardinals are the only other team with more than one representative (Pujols and Yadier Molina).

At the other end of the spectrum, Yadier's older brother, Bengie Molina, had the lowest BB% (2.50%) in baseball. Bengie struck out in 13.08% of his plate appearances, which means he whiffed more than 5x as often as he walked.

Mark Reynolds had the highest SO% (33.69%). He set a single-season record with 223 strikeouts in 2009. The 26-year-old third baseman has played three seasons in the majors and owns the top two strikeout totals in the game's history. His SO and BB rates have increased each year. The good news is that his BB% has risen 29.2% while his SO% has advanced just 8.0% since his rookie campaign in 2007.

Russell Branyan (29.50%), Jack Cust (30.23%), Adam Dunn (26.50%), Ryan Howard (26.46%), Brandon Inge (26.69%), and Carlos Pena (28.60%) stand out for their high strikeout rates. However, Inge was the only one with a walk rate (8.48%) below the league average.

Lastly, there were 13 qualified hitters with walk rates over 15%. Other than Pujols, every player in this baker's dozen bats lefthanded or both. Therefore, I believe it is safe to say that the three-time MVP is truly unique. As the graphs have shown, Pujols is the most disciplined and productive hitter in the game today.

| Designated Hitter | January 23, 2010 |

Author's Note: Ernie Harwell's birthday is January 25th. When I sat down to start writing this article last month, I had that birthday in mind as a deadline. I thank Rich for allowing me to print it here in time for time for Ernie's birthday. Happy Birthday Ernie. Listening to you broadcast a game was always a pleasure.

In 1953, a baseball fan in New York City turning the radio dial had several delightful choices. The trio of Red Barber, Connie Desmond and Vin Scully were the voices for the Dodgers; Russ Hodges and Ernie Harwell called Giant games; Mel Allen, Joe E. Brown and Jim Woods were the broadcasters for the Yankees. Never before and not since have so many excellent broadcasters congregated in one city in one season to broadcast big league baseball.

Before 1939, the three New York teams, fearful that radio play by play would curtail attendance, kept radio broadcasts out of their ballparks. There were some exceptions to the radio ban. A few opening day and other scattered games were aired. All-Star games and the World Series were broadcast on New York radio stations. However, New Yorkers were unable to hear major league baseball on a regular basis until Larry MacPhail, brought to New York from the Cincinnati Reds to take over operation of a moribund Brooklyn Dodger franchise, broke the radio blackout in 1939.

Red Barber was the first of the seven legendary broadcasters of 1953 to take the air for a New York team for a full season of games. Red's first broadcasting job, taken while he was a student at the University of Florida, was at radio station WRUF in Gainesville, Florida. During his time at WRUF, Barber was able to hear the powerful signal of Cincinnati's WLW at his home in Gainesville. Red followed that radio signal to its source to audition for a job at the radio station that has long been dubbed as "The Nation's Station" because of the wide sweep of its AM transmitter.

In 1934, Red realized his goal of a job at WLW. Powel Crosley, the owner of stations WSAI and WLW in Cincinnati, took over control of the Cincinnati Reds during the Great Depression. With a team and two radio stations, Crosley naturally looked for a broadcaster to air the games of the team he owned. There were plenty of capable broadcasters in the Cincinnati area, but the job went to the young man in Florida who had never broadcast or even seen a big league baseball game.

Red's radio work involved more than sports and baseball broadcasts. Only about twenty Reds games were broadcast on the radio in 1934, so Red worked more as a staff announcer than as a baseball broadcaster in his first year in Cincinnati. The next year Red's baseball broadcasting career blossomed. Larry MacPhail brought lights to the Reds home park in 1935, and the Reds played the Philadelphia Phillies in the first night game in major league history on May 24th. Red Barber broadcast that game over the new Mutual Broadcasting network. Red's call of the major's first night game was the first sporting event ever carried by Mutual. After the end of the regular season Red was back in the national spotlight as a broadcaster for Mutual's coverage of the 1935 World Series between the Cubs and Tigers.

Red stayed in Cincinnati until the end of the 1938 season. Powel Crosley did not want to see his talented broadcaster leave. Red was offered more money to stay in Cincinnati than he would make in Brooklyn, but the lure of greater career possibilities in New York caused Red take the Dodger job.

Mel Allen will always be remembered as the voice of the Yankees. However during his early years as a baseball broadcaster Mel was actually the voice for two major league teams, the Giants and the Yankees. After Brooklyn broke the New York radio blackout, the Yankees and the Giants in 1939 joined forces to broadcast their home games over WABC. Brooklyn broadcast its entire schedule, home and away, although road games were recreated.

The principal broadcaster for the Yankee and Giant games in 1939 was Arch McDonald, a veteran broadcaster who had done Senator games in Washington, DC. McDonald's assistant was Garnet Marks. Marks was fired early in the season, and in June of 1939, Mel Allen was hired to take his place. After the 1939 season, McDonald returned to Washington and Allen became the primary broadcaster for Yankee and Giant home games in 1940.

Like Red Barber, Mel Allen was raised in the South. At the age of fifteen Mel enrolled at the University of Alabama. After completing his undergraduate degree, he began law school, also at the University of Alabama. While in law school, Mel became the public address announcer for University of Alabama football games. Shortly before the 1935 season the radio broadcaster for University of Alabama football games quit. The P.A. announcer was transferred to the radio booth to call Alabama football and a brilliant broadcast career was born.

In 1936, Mel traveled to New York for a winter vacation. While in New York he decided to audition for a job, and he landed a staff position at CBS radio in early 1937. Allen appeared in a variety of capacities for CBS including game shows, soap operas and big band broadcasts. In 1938 Mel appeared along with France Laux and Bill Dyer for CBS radio coverage of the World Series between the Cubs and Yankees. It was the first of many World Series broadcasts for perhaps the most recognizable voice in baseball broadcasting history.

Connie Desmond was the third of the seven legendary broadcasters to arrive in New York. In 1942 Desmond was hired to work at radio station WOR. Connie began his broadcasting career in 1932 in his hometown, Toledo, Ohio. During the 1942 baseball season, Connie teamed up with Mel Allen to broadcast Giant and Yankee home games over WOR. Connie also worked at WOR in a variety of capacities, including music shows that featured his own singing.

Red Barber's assistant broadcaster, Al Helfer, went into the military after the 1942 season. Desmond met with Barber and asked for Helfer's job. Connie was hired as Barber's assistant. In 1943 the Giants and Yankees did not broadcast any of their games, so Connie and Red were the only big league broadcasters on the air in New York during the 1943 season.

After World War II, a pivotal figure in New York baseball broadcasting returned from military duty. Larry MacPhail returned to New York, but not with the Dodgers. MacPhail became a co-owner of the Yankees and once again he brought change to baseball broadcasting in New York. MacPhail was not satisfied with the broadcasting partnership between the Giants and Yankees. In 1946, the Yankees began broadcasting all their games, home and away, on WINS. Mel Allen, also out of the military, returned as the principal Yankee broadcaster. The Giants hired Jack Brickhouse as their primary broadcaster in 1946. For the first time, all three New York teams were on the radio for a complete season of home and away games.

Russ Hodges was the fourth of the legendary broadcasters to reach New York. In 1946, Russ was hired to assist Mel Allen on Yankee broadcasts. Before taking the Yankee job, Hodges broadcast for the Cubs and White Sox in Chicago, and for the Senators in Washington, DC. Like Allen, Russ Hodges was a law school graduate. Hodges stayed with the Yankees until the Giants hired him to be their primary broadcaster for the 1949 season.

Ernie Harwell arrived in New York during the 1948 season to broadcast for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Ernie began his baseball career at an early age. When he was five years old he was a bat boy for visiting teams of the minor league Atlanta Crackers. At the age of sixteen, Ernie became the Atlanta correspondent for the "Baseball Bible," the Sporting News. Harwell began his broadcasting career at WSB in Atlanta in 1940 after graduating from Emory University. Ernie broadcast Atlanta Cracker games before the war, and after being discharged from the Marines, he resumed his baseball broadcasting career with the Crackers in 1946.

Ernie was brought to New York to fill in for an ailing Red Barber during the 1948 season. That year, the Dodgers began live broadcasts of their road games. Red Barber became severely ill with a bleeding ulcer during a Dodger road trip. Connie Desmond took over as the sole broadcaster for the Dodgers while Dodger management sought a replacement for Red. The Dodgers looked to Atlanta and the talented Harwell to fill in during Red's illness. However, Ernie was under contract to the Crackers, so Ernie's boss in Atlanta, Earl Mann, needed to be compensated for losing his play by play broadcaster. For the only time in major league history, a team traded a player for a baseball broadcaster when the Dodgers shipped minor league catcher Cliff Dapper to Atlanta for the services of play-by-play broadcaster Ernie Harwell.

Ernie remained with Red Barber and Connie Desmond through the end of the 1949 season. Ernie left the Dodgers to join Russ Hodges in broadcasting New York Giant games in 1950. To the delight everyone who has had a chance to listen to him during the past sixty years, Red Barber chose Vin Scully to replace Ernie in the Dodger broadcast booth.

Vin Scully graduated from Fordham in 1949. While he was in college he worked at the campus FM station and also played the outfield on the varsity baseball team. Vin sent letters to radio stations up and down the Eastern seaboard in search of a broadcasting job after graduation. He landed a temporary job as a summer replacement announcer in Washington, DC for the CBS affiliate, WTOP. Management at WTOP appreciated his talent, but at the end of the summer, they had no permanent job for him. Vin left Washington with a promise of a future job at WTOP, but no immediate employment.

Vin returned to his home in New York and contacted CBS radio in search of a job. Vin was able to meet with Ted Church, who was director of CBS radio news. Church had no job for him, but he did introduce Vin to Red Barber, who in addition to being the Dodger play-by-play broadcaster, was the director of sports for CBS radio. Red had no job to offer, though he was favorably impressed after talking with the youngster.

One of Red's primary duties as director of sports for CBS radio was selecting broadcasters to go to various college games throughout the country for the CBS college football roundup show. Luckily for Vin, in 1949 Red was unable to find a broadcaster for the Boston University-University of Maryland football game played at Boston's Fenway Park. Red remembered the young man he had met at CBS headquarters in New York and arranged for Vin to fill in at the last minute in Boston. Vin's performance impressed Red enough to give the youngster another assignment on the football roundup and a chance to be a major league broadcaster for the Dodgers.

Vin joined the Dodger broadcast booth after an eventful meeting with Red Barber and Branch Rickey that took place after Red returned to New York from a 1949 college football broadcast on the West coast. In an interview with author Ted Patterson for the splendid book, The Golden Voices of Baseball, Vin recalled the terms of his employment: "The agreement reached was that I would go to spring training on a one-month option. Either I make it, or they could lose me in the Everglades."

Jim Woods was the last of the seven legendary broadcasters to reach New York. In 1953, Jim teamed with Mel Allen to broadcast Yankee games. Joe E. Brown joined Woods and Allen for some Yankee broadcasts, but Brown primarily worked on the Yankee pre- and post-game shows. Woods had an eventful career before he arrived in New York. Jim replaced Ronald Reagan as the football radio voice of the Iowa Hawkeyes in 1939. After spending four years in the military during World War ll, Woods eventually landed in Atlanta where he replaced Ernie Harwell after Ernie left the Crackers to broadcast for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Woods followed Ernie's path to New York as a major league broadcaster in 1953.

The seven splendid broadcasters were together in New York for just one season. Ernie Harwell left the Giants to become the principal broadcaster for the Baltimore Orioles in 1954. Harwell's departure was not the only shift in the New York baseball broadcasting landscape. After the 1953 season, Red Barber left the Dodgers to join Mel Allen and Jim Woods in the Yankee broadcast booth.

Vin Scully and Connie Desmond continued as Dodger broadcasters in 1954. However, Connie missed some games because of alcoholism. In 1955, the only year Brooklyn won the World Series, Connie was gone from Dodger broadcasts. Dodger owner Walter O'Malley gave Connie a last chance to continue his career in 1956, but when Connie began drinking again, he was replaced for good by Jerry Doggett before the end of the season.

The Yankee broadcast team of Mel Allen, Jim Woods and Red Barber stayed together until the end of the 1956 season. Phil Rizzuto, whose Yankee playing career ended in 1956, was hired to replace Woods as a Yankee broadcaster. Woods was able to stay in New York by shifting to the Giants broadcast booth in 1957.

The departure of the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants for Los Angeles and San Francisco after the 1957 season forever changed the face of baseball and baseball broadcasting in New York. Vin Scully and Russ Hodges relocated with their teams to the West coast. Remarkably, in 2010, Vin will begin his 61st consecutive season as a Dodger broadcaster. After the 1957 season, Jim Woods departed New York for Pittsburgh, where he teamed with Bob Prince to form one of the best play-by-play tandems in the history of baseball broadcasting.

In 1964, Mel Allen was fired by the Yankees. Mel broadcast for the Atlanta Braves and Cleveland Indians after leaving New York. Mel returned to the Yankees as a cable-TV announcer for SportsChannel in 1978. His primary fame though after 1964 was as the voice for the popular TV show, This Week in Baseball. TWIB with Mel Allen was on the air for seventeen terrific years.

Red Barber, the man who in 1939 was the first broadcaster for a New York team, was the last of the seven legendary broadcasters of 1953 to broadcast for a team in New York. After the 1966 season Red was fired by the Yankees. In the last years before his death, Red returned to radio as a regular guest of Bob Edwards on NPR's Morning Edition.

Sources:

Sports on New York Radio: A Play by Play History by David J. Halberstam is an absolute gem for anyone interested in the history of sports broadcasting. Ted Patterson's Golden Voices of Baseball is rich in pictures and commentary about the history of baseball broadcasting. The book includes two CD's containing excerpts of the author's interviews with various broadcasters. Both books are well worth their purchase price.

Also useful in this article were interviews of Vin Scully and Red Barber broadcast on Larry King's radio show for Mutual in 1982. A partial transcript of the King-Barber interview is available at Dodger Thoughts. I also used material from a radio program produced by a Cincinnati NPR station that was narrated by Marty Brennaman. The CD is available for purchase through the Cincinnati radio station's internet site.

Ross Porter's essay about Ernie Harwell, gives some details about Ernie's life that I included in my article. Also, Ernie has an audio scrapbook that is rich in information and is a delight to hear. It is available for purchase on the internet.

Some of the material about Mel Allen was taken from Mel's obituary in the New York Times. The obit from the New York Times is online. There are a few errors in the obituary though. Also helpful was a taped interview of Mel done by baseball broadcast historian Curt Smith.

Stan Opdyke grew up on the East Coast listening to baseball on the radio. He still prefers baseball on the radio (if the broadcasters are good) to baseball on TV.

| F/X Visualizations | January 22, 2010 |

Nick Steiner, who over the last couple months has been producing some great pitchf/x content, had an interesting piece asking how many HRs Albert Pujols would hit if he saw the same pitches as Juan Pierre. He wrote the piece in mid-September and concluded he would have hit 62 HRs up to that point in the season. It is a very cool question, and implicit in it the question is the understanding that pitchers pitch differently to good hitters than they do to not-quite-as good hitters.

I think this is a very interesting idea to explore further, and the PITCHF/X data set is a great tool for it. To do that I created two groups of hitters. First the twenty regulars with the top wOBAs in 2009 (wOBA is a stat of TangoTiger's construction that measures overall offensive impact), and second the twenty regulars with the lowest wOBAs in 2009.

One common assumption is that good hitters see fewer fastballs and this analysis bears this out. The top-wOBA group saw 58.4% fastballs versus 61.5% for the bottom-wOBA group. But that actually understates the difference. The top group saw many more pitches in hitter's counts and pitchers throw more fastballs in hitter's counts. It is best to consider the difference in each count.

Fastball Frequency by count

top bottom

0-0 0.626 0.663

0-1 0.551 0.545

0-2 0.549 0.511

1-0 0.587 0.664

1-1 0.542 0.559

1-2 0.497 0.484

2-0 0.659 0.780

2-1 0.579 0.679

2-2 0.530 0.528

3-0 0.717 0.848

3-1 0.735 0.823

3-2 0.591 0.705

Here you can see the difference is largely driven by hitter's counts (e.g., 1-0, 2-0, 2-1, 3-0, 3-1) where the top group saw on average 10% fewer fastballs than the bottom group. Interestingly in pitcher's counts (e.g., 1-2, 2-2) the differences are very small.

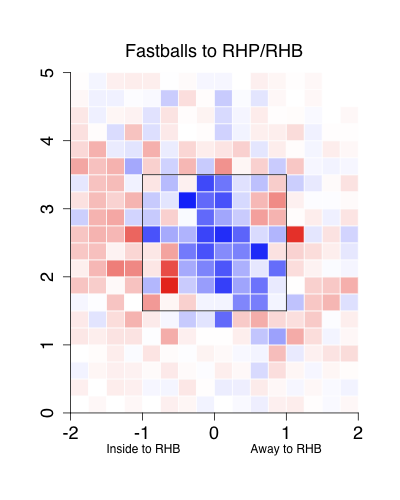

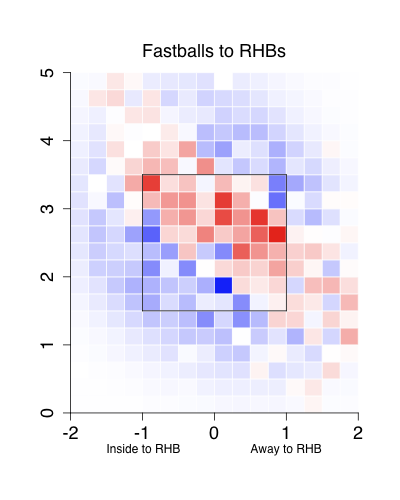

The next thing we can look at is where those pitches end up. Here I plot the location of fastballs to the two groups. Areas where the top-wOBA group sees more pitches are red and where the bottom-wOBA group are blue.

Not surprisingly the top group sees many fewer balls in the strike zone. The extra pitches end up inside more than they end up outside, which is a little surprising to me. This also shows that the pattern of good hitters seeing fewer pitches in the zone is not just a result of them seeing fewer fastballs, which are more likely to be in the zone. That is good hitters see fewer fastballs AND the ones they do see are less likely to be in the strike zone.

Overall the top group saw 47.6% of their pitches in the strike zone, compared with 51.8% for the bottom group. But again this 4% difference understates the difference because the top group gets more hitter's counts in which pitchers should be around the zone. Breaking up by count we see:

Proportion of pitches in the strike zone

top bottom

0-0 0.507 0.548

0-1 0.428 0.473

0-2 0.325 0.325

1-0 0.505 0.575

1-1 0.478 0.526

1-2 0.376 0.424

2-0 0.505 0.592

2-1 0.545 0.580

2-2 0.443 0.489

3-0 0.471 0.554

3-1 0.607 0.646

3-2 0.553 0.598

Here the difference increases to 4% to 7% in each count. It is clear the pitchers avoid the heart of the zone, and the zone as a whole, against the better batters.

This is another example where the pitchf/x data support the prevailing assumptions: good hitters see fewer fastballs and fewer pitches in the zone. But there are some interesting patterns: the smaller frequency of fastballs seen by good batters is largely driven by a much smaller frequency in hitter's counts -- not all counts across the board -- and the out of zone fastballs that good hitters see are more likely to be inside than outside.

| Change-Up | January 21, 2010 |

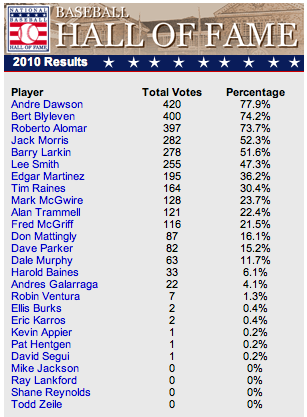

Recently, former New York Times journalist and J.G. Taylor Spink Award winner Murray Chass took to the pages of his blog titled Murray Chass On Baseball to discuss Hall of Fame voting. He addressed an array of topics, from Hall voting eliciting strong opinions, to Tommy John's Hall of Fame candidacy, to my own personal "track record". There's no need to FJM someone like Chass - he's just writing on his blog that he refuses to acknowledge is a blog, snarling at (certain) stats and just sort of watching the world pass him by. Honestly, it has to be difficult. On a human level, I pity Murray Chass.

Since I guess Chass probably maintains a broad readership and has decided to come at me personally in his column, I suppose I should respond to a few of the points he made. It's evident to me that Chass doesn't like the tone of the Hall of Fame debate, and I suppose that's reasonable. Heck, we get awfully passionate around here about it, maybe excessively so on occasion. Chass points out one reader who emailed to say that one candidate "clearly deserved" enshrinement, and Chass thought that language was too strong. Fine, I suppose, but surely there are "clearly deserving" Hall candidates, no? Anyway, and Craig Calcaterra has already dealt with this nicely, problems arise when Chass veers off "can't we all just get along" course and into this:

“Clearly deserve” in whose judgment? His, of course. Does that make him right and me wrong? Of course not. Am I right? Yes. Why? Because my opinion counts and his doesn’t. My ballot was one of the 539 counted in the election. He did not have a vote. Therefore, his opinion is worthless as far as the election is concerned.That’s the real problem self-proclaimed experts have. They want to be the ones voting, but they don’t have that privilege. It’s their own fault. They chose the wrong profession. Accountants, lawyers, doctors, teachers and salesmen don’t get to vote for the Hall of Fame. Baseball writers do.

Someday, a curious individual might set out to understand why it was that baseball websites were able to amass strong followings at a time when the profession of mainstream media baseball writing was still so entrenched in American culture. How could Rob Neyer and Nate Silver and Jonah Keri and Joe Sheehan and Keith Law and David Cameron and Sky Andrecheck and Cliff Corcoran have risen to such prominence, when the baseball writing establishment was still churning out columns? Well, that individual researching why it was that new internet baseball writers succeeded will stumble across what Chass has written above, and it will all make sense.

You don't get credibility because you hung around clubhouses for 30 years. Or because you traveled on the team plane, have had cocktails with Lou Gorman, were at Fenway the day Bucky Dent hit his home run or because you can recall the fear in opposing pitchers' eyes as Jim Rice came to the plate. You don't even get credibility because you have a vote. You get credibility by doing good work. And if your work is good, it stands on its own. If a new age of writers comes along with a new way of thinking about the game, and a new medium like the internet emerges, you don't kick and scream and yearn for yester-year, you evolve and learn and continue to do good work.

As for the notion that a non-voter's opinion is "worthless", tell that to Bert Blyleven or the proprietor of this site. Blyleven has publicly expressed gratitude for Rich Lederer time after time, and recently Peter Gammons praised Rich's work as well. About a dozen writers have explicitly attributed their Blyleven support to Rich's Blyleven series. How many more writers have been persuaded and not admitted as much? Rich may not have a vote, and he may not have swayed Murray Chass, but his opinion is anything but "worthless".

To be sure, there are nobler causes to take up, but there is virtue in working to ensure the Hall of Fame voting process is more just. A baseball career is a man's life's work, and there is no more prestigious recognition than to be enshrined in Cooperstown. So if Murray Chass and Dan Shaughnessy can't be bothered to figure out who the best players were, others will have to take it up. Whether we're writers or salespeople or money managers or entrepreneurs or consultants or lawyers, we'll take it up. We'll do so by building strong cases for the candidates we think deserve enshrinement, and we'll do so by exposing and discrediting flimsy logic. Because flimsy logic, when it comes to the Hall of Fame, can lead to a man's life's work being remembered in the wrong light, or even not remembered at all. Readers, fans, other voters - they'll be the ones to decide whose judgment should be called into question. Not Murray Chass through a baseless assertion on his baseball blog.

==========

As I noted at the outset, Chass also came at me personally in his blog entry, and I want to address it quickly. It was actually quite harmless but let me just offer up a few thoughts. Chass wrote the following...

Patrick Sullivan, a name unknown to me, ridiculed Dan Shaughnessy, a highly respected columnist for the Boston Globe, for writing that … well, just about anything. I don’t know that Shaughnessy wrote a sentence that Sullivan didn’t ridicule.One of the statements he faulted Shaughnessy for was his belief that Jack Morris was better than Curt Schilling. Preposterous, Sullivan suggested. True, I say in agreement with Shaughnessy. But then I would probably take Shaughnessy’s view over Sullivan’s on any subject. Shaughnessy has a track record; Sullivan doesn’t, as far as I know.

I have had a similar debate with a reader over Morris and Bert Blyleven. Like Sullivan in his case for Schilling, the reader used statistics to argue his case for Blyleven. Most of the Hall arguments today seem to be statistics-centered.

All I can say is if you're going to be called out in public by a washed-up sportswriter on his baseball blog, this is how you want it to be done; in a fashion that is so self-evidently discrediting. We learned three things from this Chass excerpt:

1. Chass thinks Shaughnessy is right and I am wrong because Shaughnessy has a track record with which he's familiar.

2. Chass thinks Shaughnessy would be right and I would be wrong on ANY subject because Shaughnessy has a track record as a baseball sportswriter and I do not.

3. He thinks Jack Morris was better than Curt Schilling.

Two thoughts. One, how harebrained do you have to be to admit freely that you won't entertain the merits of a particular argument, but rather will simply appeal to authority? What a great way to discredit your whole philosophy in one fell swoop.

Two, and I can't be clear enough about this. If you think Jack Morris was a better pitcher than Curt Schilling, THEN YOU DON'T KNOW THE VERY FIRST THING ABOUT BASEBALL. Talk about life's work? The life's work of Murray Chass, all those days and nights hanging around a smelly clubhouse, and what does he have to show for it? A baseball mind that leads him to believe that Jack Morris is better than Curt Schilling. It's nothing short of embarrassing.

The piece ends the way so many of these do. After berating those of us who look to statistics to form the basis of our baseball-related arguments, he transitions to Tommy John's Hall of Fame case, comparing his to Blyleven's.

John had a career 288-231 record with a 3.34 earned run average. Blyleven’s record was 287-250 and his e.r.a. 3.31. John retired 57 percent of the batters he faced, Blyleven, with all his strikeouts, 59 percent.

Yup, stats. But not just any stats, moronic, wrong stats that say Tommy John yielded a career .430 on-base percentage and Bert Blyleven yielded a .410 figure. Truth is, John's career on-base against was .315 while Blyleven's was .301. I am not sure where that gets us, but at least we're dealing in reality.

Anyway, back away from the word processor, Murray. People, successful people, knowledgeable people who adore baseball, are all laughing at you.

| Touching Bases | January 21, 2010 |

While a pitcher's stuff diminishes over the course of game, the effects I found were relatively small. So why do batters gain an edge over pitchers as the game goes on? Well, baseball is a game of adjustments. Batters get their timing down and start picking up the ball out of the pitcher's hand. All that good stuff.

The first time a batter faces a curveball, he might be caught off-guard. That’s why pitchers throw predominantly fastballs the first time through the order. And that’s why batters do so well the third time they face a pitcher. They’ve seen most of his repertoire, and are able to recognize the curve. As the saying goes, “Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me…you can’t get fooled again.”

First, here is the average run value per 100 pitches based on the number of times a batter has seen a given type of pitch. I include all data points for which I have approximately 1,000 pitches.

For reference:

F2: Sinker/Two-Seam Fastball

F4: Four-Seam Fastball

CB: Curveball

SL: Slider

CH: Changeup

FC: Cut Fastball

This chart indicates that a batter facing a fastball from the same pitcher for the 12th time will perform better than a batter facing a pitcher's first fastball. Chances are, however, that batters who face 12 fastballs are better from those who only face a few. One way to get around this bias might be to take the difference in run value between the 11th fastball and 12th fastball. This method, called the delta method, allows you to compare apples to apples as each change in measurement is at least composed of players from the same sample. This produced the following chart:

The magnitude of the results is enormous, if the results are to be believed. A batter facing a changeup for a fifth time is expected to perform over five runs per 100 pitches better than he performs the first time he saw the changeup. That's pretty much the difference between the best and worst hitter in the league. Unfortunately, I have to say that I don't think the delta method is the way to go here, and I'm not sure how to fix my sampling problems. Batters who face at least three changeups have a rv100 of 0.2 on the third changeup, but they only have an rv100 of -1.1 on the second change. This is a delta of 1.3 runs. Meanwhile, batters who face at least four changeups have an rv100 of -1.3 runs on the third change and 0.3 on the fourth, another huge delta of 1.6 runs. This would mean that batters perform three runs per 100 pitches better on the fourth changeup they see than on the second. The oddity here is that batters who face at least three changeups are above average on the third changeup, but batters who face at least four changeups are well below average on the third changeup. I think what this means is that once pitchers get burned on a given pitch, they quit throwing it to that batter the rest of the game. I don't know how to solve for these biases.

I went on and produced the same two charts, except this time at the at-bat level instead of the game level.

Batters who face seven fastballs in an at-bat are good, in that they are able to work the count. Meanwhile, pitchers who throw five sliders in an at-bat are good, in that they are either ahead in the count or can locate their breaking balls.

Using the delta method:

No pitch gains in effectiveness after its been thrown once already in an at-bat. This finding was applicable at the game level as well. However, there are differences between the at-bat and game level. Off-speed pitches such as the changeup and curveball lose more value than fastballs during the game, given an even distribution of pitches. But in an at-bat, off-speed pitches do not lose as much effectiveness as fastballs when they're repeatedly thrown. It makes sense to me that changeups are the worst pitch to show multiple times to the same batter throughout the game, since the success of changeups is built on deception. Yet I'm not sure why changeups don't lose as much effectiveness in an at-bat once thrown multiple times as fastballs do. I think it has something to do with the count in which they're thrown and the theory of the out pitch.

| Change-Up | January 20, 2010 |

The Chicago Cubs boast a core group of championship caliber position players that includes Aramis Ramirez, Derrek Lee, Geovany Soto, Alfonso Soriano, Marlon Byrd, Kosuke Fukudome and Ryan Theriot. Their front three starting pitchers, Ted Lilly, Ryan Dempster and Carlos Zambrano, form a perfectly adequate top end of a World Series aspirant club. In the bullpen, arms like Carlos Marmol, Angel Guzman, John Grabow and Sean Marshall offer Manager Lou Piniella a pool of live and (often) dependable arms for late in ballgames. All of this is to say that the Cubs, as currently constituted, look like a solid club.

Of course a "solid club" when you're looking up at the St. Louis Cardinals might not do the trick and to their credit, the Cubs are looking to round out their roster with a player or two still available on the free agent market. As I concluded in my piece over the weekend, it's likely that the Cubs will still have a strong pitching staff, just not one that stacks up to their outstanding 2009 unit. They can expect some improvement offensively, but for a team looking to make a big leap from 83 wins to contender, it doesn't look like the offense will do enough to get them over that line. The Cubs are looking for another starter.

Now, if you were to diagnose what went wrong with the Chicago Cubs in 2009, you would point to four separate players. Soriano and Soto battled injuries and sub-par performance all season long, Ramirez missed too many games and Milton Bradley failed to live up to his potential. The Cubs signed three of those four players to splashy free agent contracts, and Soto was the 2008 NL Rookie of the Year. All four are stud talents, and while the Cubs SHOULD be able to pencil in improvement from Soriano, Soto and Ramirez (Byrd fills in for Bradley), there is still a high-risk high-reward element at play.

This brings me to their starting pitching decision. The Cubs are rumored to be in hot pursuit of right-handed pitcher Ben Sheets, the man whose medicals are said to be disastrous. Even for smallish money, the choice to depend on Ben Sheets for 2010 would amount to a classic high risk/reward strategy for Chicago. With lingering uncertainty offensively, why fill out a borderline contender with another player who brings along as much downside as Sheets would?

If one were to assess where the Cubs might struggle in 2010, you might start with starting pitching depth. With the likes of Tom Gorzelanny, Randy Wells, and good grief, Carlos Silva filling out the back end of the rotation, and with some injury concerns surrounding Lilly and Zambrano, I am not sure a flier on Sheets is the play. Make me in charge of Cubs personnel choices and I would opt for the guy I know will take the ball every fifth day and give the offense a chance to win the game. In my estimation, the right target for the Cubs would be Jon Garland.

Garland is by no means the superstar some might have thought he would become after his breakout 2005 campaign with the Chicago White Sox, but his 162-game career average of 208 innings at a 104 ERA+ clip could be just what the doctor ordered for a Cubs team searching for stability.

| Behind the Scoreboard | January 18, 2010 |

Baseball America's farm system rankings are one of the most respected rankings of a club's minor league talent around. Since 1984, they've been rating and ranking minor league systems in terms of their potential for major league impact. In this post, I try to determine just how much of an impact a team's farm system has on future performance.

Recently, the Baseball America came out with its December farm system rankings. Baseball America had the Houston Astros dead last, while the Rangers were ranked #1. If you're a Rangers fan, you might be smiling ear to ear, believing that the Rangers, who were also ranked #1 in 2009, would be poised for a long-term dynasty. Meanwhile Astros fans might despair, knowing that good young talent is not on the way.

But really, how predictive are these rankings? Does a good ranking actually lead to future success? If so, just how much?

To test this, I obtained Baseball America's organizational rankings from 1984-2010. I first transformed the rankings into a ratings, assuming that teams' minor league talent was normally distributed. This reflected the likely reality that the difference between having the #13 and #17 farm system is pretty small, but the difference between the #1 and #5 farm system is quite large. Transforming the ratings into normally distributed scores (which range from about -2.1 to 2.1) reflects this nicely.

I then used statistical regression to find the relationship between Baseball America ratings and team winning percentage. Doing a simple, single-term linear regression, it appears that the Baseball America rankings have predictive power for many years forward. One year's Baseball America ranking has a statistically significant effect on winning percentage for each of the next 8 years. As you would expect, those with higher rankings will tend to do better. If the only information you have is a team's 2010 Baseball America ranking, you would predict that a team with good rankings now will have an advantage come 2018.

But of course, we have more information than that. To really get at the heart of the matter, we need to take into account potential confounding variables. We can take these into account by using a multiple regression. To predict the next year's WPCT, significant important factors were:

a) WPCT from last year

b) WPCT from two seasons ago

c) Salary from this season

d) Salary from last season

e) Market size

Now, to test the effect of farm systems, we can add in the Baseball America rankings data. When we do, we get an interesting, yet difficult to interpret model, the results being the following:

*market size was also transformed from a ranking to a normalized rating

**salary variables were expressed as a ratio of team salary to league-average salary

Clearly the salary and previous winning percentage variables are the main predictors of a team's success in a season, with market size close to significant. Less clear is the Baseball America rankings, which don't have a clear pattern. The years with most predictive power are the rankings from the previous season and from four seasons ago. Rankings from two years ago and from seven years ago show some predictive power, but not a lot. Meanwhile the other years show very little predictive power, with the effect being negative in some years.

The reason for this volatility of course is that the sample size is fairly small, so the estimates are not all that accurate. While using these weights would give the best fit, it doesn't seem to make sense that a BA ranking from one or four years ago would have much more predictive value that the BA ranking from two or three years ago. What does appear clear however, is rankings from the previous four years combined have a pretty strong correlation with WPCT, while rankings from after that time, on the whole, don't really a strong much effect.

My imperfect solution, then is to put the average of the previous four years of BA rankings into the model. When I do this, I get the following result.

Overall, the values of the other terms are relatively unchanged, but we get a nice, highly significant, result for the Baseball America rankings. What does it all mean? Those ranked as the #1 farm system for the previous four years would get the maximum Baseball America score of 2.1. Multiplying 2.1 by .0155 gives means that it would be expected to add about .033 points to its WPCT in the next season. That translates to about 5.3 wins. Now five and a half wins is nothing to sneeze at, but it’s also not an enormous factor. Teams with weak farm systems do take a hit in future production, but it's certainly not insurmountable. The Astros, ranked last now for three consecutive years, figure to take a hit of 3.3 wins in 2010 and 4.4 wins in 2011. While that's certainly not desirable, there's no reason they still can't compete in the coming years, despite a poor farm system.

The model can be extended to predict values further into the future as well. Using only known, WPCT's, salaries, market size, and Baseball America rankings, we can build models for years down the road. For instance, using only known 2010 variables, how many wins does the #1 farm system provide in 2015? The models show that being the best farm system in 2010 correlates to about 4 extra wins in 2015.

The Rangers should feel good, but not get too overconfident, despite having the #1 system in both 2009 and 2010. The Rangers, who were ranked #1 in '09 and '10, were ranked #27 in 2008 and #15 in 2007. What do the models show the Rangers farm system producing over the next several years? The models predict the following boost in wins:

2010: 1.2 games

2011: 2.6 games

2012: 5.2 games

2013: 5.6 games

2014: 4.9 games

2015: 3.8 games

2016: 3.3 games

2017: 3.1 games

2018: 2.1 games

Since the Rangers' system was rated #27 as recently as 2008, the expected farm impact in 2010 is small. However, the impact increases dramatically starting in 2012. Overall, over the next 9 years, the Rangers farm system will likely net them 31 extra wins, meaning that while their system won't have a huge effect in any one particular year, it's likely to have a strong impact on the Rangers franchise over the next decade.

How about for their Texas counterpart, the Houston Astros? For them, the following 9-year outlook looks as follows:

2010: -3.3 games

2011: -4.4 games

2012: -6.0 games

2013: -5.6 games

2014: -4.9 games

2015: -3.8 games

2016: -3.3 games

2017: -3.1 games

2018: -2.1 games

For the Astros, it's nearly the opposite situation. Their farm system projects to cause them to lose over 36 games over the next ten years. So, is the difference between the Rangers and Astros farm systems really 67 wins over the next nine years? It would appear that way, although there are some caveats. For one, the year-to-year farm system rankings are correlated with one another, so the fact that the Rangers have a good farm system now is also indicative that they will have a good system in the future. That undoubtedly accounts for some of the large difference in wins. While the Rangers may not be still reaping fruit from their 2010 farm system in the year 2018, the fact that they have a good farm team now bodes well for their future farm teams, and hence their future major league teams.

Another factor to consider is how teams go about team-building. The fact that the Rangers have a good farm system means that they may be in strong contention in the next few years. With the team blossoming, this may spur the front-office to go out and sign free agents to supplement the team. Thus, the wins the future free agents provide are also correlated with the Rangers having a good farm team. While the Rangers may win more because of the free agents, this boost (reflected in these numbers) is not necessarily a direct product of having a good farm system in 2010.

For these reasons, I would hesitate to put a dollar value on having the #1 farm system in baseball vs. the #30 farm system in baseball - at least using this analysis. There are too many potential confounding variables here such as the ones I mentioned above. Still, if you are a fan, it matters little where your team's wins are coming from. Rangers fans really do have a reason to be smiling. While a handful of wins each year may not have a major impact, 30 wins over the next 9 season is a significant force. Whether the Rangers can parlay those wins into championships remains to be seen.

The following graph shows some trajectories for some of the more extreme teams in the league:

The results also are a testament to the accuracy and relevance of the Baseball America organizational rankings. While obviously a #1 ranking doesn't guarantee championships, the ranking is significant predictor of major league wins far into the future. Kudos to Baseball America for doing these rankings. Their well-respected reputation is well-deserved.

| Designated Hitter | January 18, 2010 |

The game of baseball as played today at the amateur level is very different from the game I played growing up in Rumford, Maine in the early 1960s. In my youth, wood bats ruled. Nowadays, almost no one outside the professional level uses wood bats, which have largely been replaced by hollow metal (usually aluminum) or composite bats. The original reason for switching to aluminum bats was purely economic, since aluminum bats don’t break. However, in the nearly 40 years since they were first introduced, they have evolved into superb hitting instruments that, left unregulated, can significantly outperform wood bats. Indeed, they have the potential of upsetting the delicate balance between pitcher and batter that is at the heart of the game itself. This state of affairs has led various governing agencies (NCAA, Amateur Softball Association, etc.) to impose regulations that limit the performance of nonwood bats. The primary focus of this article is on the techniques used to measure and compare the performance of bats.

Any discussion of bat performance needs to begin with a working definition of the word “performance.” Or, said a bit differently, what is meant by the statement, “bat A outperforms bat B”? Among people who have thought about this question, a consensus has emerged that a good working definition of performance is batted ball speed (or simply BBS). Generally speaking, if you want to improve your chances of getting a hit, then you want to maximize BBS, regardless of whether you are swinging for the fences or just trying to hit a well-placed line drive through a hole in the infield. The faster the ball comes off the bat, the better are your chances of reaching base safely. So, we will say that bat A outperforms bat B if the batter can achieve higher BBS with bat A than with bat B.

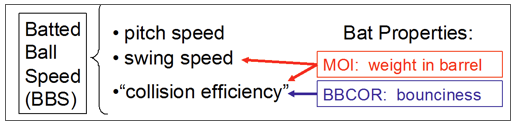

Which then brings up the next question: What does BBS depend on? I answer that by writing down the only formula you will find in this article:

This “master formula” is remarkably simple in that it relates the BBS to the pitch speed, the bat speed, and a quantity q that I will discuss shortly. It agrees with some of our intuitions about batting. For example, we know that BBS will depend on the pitch speed, remembering the old adage that `'the faster it comes in, the faster it goes out.'' We also know that a harder swing—i.e., a larger bat speed--will result in a larger BBS. All the other possible things besides pitch and bat speed that BBS might depend on are lumped together in q, which I will call the “collision efficiency.” As the name suggests, q is a measure of how efficient the bat is at taking the incoming pitch, turning it around, and sending it along its merry way. It is an important property of a bat. All other things equal, when q is large, BBS will be large. And vice versa. For a typical 34-inch, 31-oz wood bat impacted at the “sweet spot” (about 6 inches from the tip), q is approximately 0.2, so that the master formula can be written BBS = 0.2*(pitch speed) + 1.2*(bat speed). This simple but elegant result tells us something that anyone who has played the game knows very well, at least qualitatively. Namely, bat speed is much more important than pitch speed in determining BBS. Indeed, the formula tells us that bat speed is six times more important than pitch speed, a fact that agrees with our observations from the game. For example, we know that a batter can hit a fungo a long way (with the pitch speed essentially zero) but cannot bunt the ball very far (with the bat speed zero). Plugging in some numbers, for a pitch speed of 85 mph (typical of a good MLB fastball as it crosses home plate) and a bat speed of 70 mph, we get BBS=101 mph, which is enough to carry the ball close to 400 ft if hit at the optimum launch angle. Each 1 mph additional pitch speed will lead to about another 1 ft, whereas an extra 1 mph of bat speed will result in another 6 ft. On the other hand, if the bat were a “hotter bat” with q=0.22, that would add 3 mph to BBS, adding a whopping 18 ft to a long fly ball.

The master formula tells us that the quantities that determine bat performance are the collision efficiency and the bat speed, leading us to ask our next question. What specific properties of a bat determine its bat speed and collision efficiency? There are two such properties: the ball-bat coefficient of restitution (BBCOR) and the moment of inertia (MOI). In the following paragraphs, I’ll explain what these properties are and how they contribute to bat performance. The interplay among the various quantities is shown schematically in the picture below.

Let’s start with the BBCOR, which is a measure of the “bounciness” of the ball-bat collision. First a brief digression. During a high-speed ball-bat collision, the ball compresses by about 1/2 of its natural diameter and sort of wraps itself around the bat, as shown in the accompanying photo. It then expands back out again, pushing against the bat. During this process, much of the initial energy of the ball is converted to heat due to the friction from the rubbing of threads of yarn against each other. Try dropping a baseball onto a hard rigid surface, such as a solid wood floor. The ball bounces to only a small fraction of its initial height, reflecting the loss of energy in the collision with the floor. A wood bat with its solid barrel behaves more or less like a rigid surface. But a hollow aluminum bat is different since it has a thin flexible wall that can “give” when the ball hits it. Some of the ball’s initial energy that would otherwise have gone into compressing the ball instead goes into compressing the wall of the bat. The more flexible the wall, the less the ball compresses and therefore the less energy lost in the collision. This process is commonly called the “trampoline effect,” and the BBCOR is simply a quantitative measure of that effect. A wood bat has essentially no trampoline effect and has a BBCOR ≈ 0.50. Hollow bats can have a substantially larger BBCOR, leading to a larger q and a correspondingly larger BBS. For example, a bat with BBCOR = 0.55 will have about a 5 mph larger BBS. Indeed, the technology of making a modern high-performing bat is aimed primarily at improving the trampoline effect—i.e., increasing the BBCOR and consequently the BBS. For aluminum this is achieved by developing new high-strength alloys that can be made thinner (to increase the trampoline effect) without denting. The past decade has seen the development of new composite materials that increase the barrel flexibility beyond that achievable with aluminum, giving rise to a new generation of high-performing bats.

Let’s start with the BBCOR, which is a measure of the “bounciness” of the ball-bat collision. First a brief digression. During a high-speed ball-bat collision, the ball compresses by about 1/2 of its natural diameter and sort of wraps itself around the bat, as shown in the accompanying photo. It then expands back out again, pushing against the bat. During this process, much of the initial energy of the ball is converted to heat due to the friction from the rubbing of threads of yarn against each other. Try dropping a baseball onto a hard rigid surface, such as a solid wood floor. The ball bounces to only a small fraction of its initial height, reflecting the loss of energy in the collision with the floor. A wood bat with its solid barrel behaves more or less like a rigid surface. But a hollow aluminum bat is different since it has a thin flexible wall that can “give” when the ball hits it. Some of the ball’s initial energy that would otherwise have gone into compressing the ball instead goes into compressing the wall of the bat. The more flexible the wall, the less the ball compresses and therefore the less energy lost in the collision. This process is commonly called the “trampoline effect,” and the BBCOR is simply a quantitative measure of that effect. A wood bat has essentially no trampoline effect and has a BBCOR ≈ 0.50. Hollow bats can have a substantially larger BBCOR, leading to a larger q and a correspondingly larger BBS. For example, a bat with BBCOR = 0.55 will have about a 5 mph larger BBS. Indeed, the technology of making a modern high-performing bat is aimed primarily at improving the trampoline effect—i.e., increasing the BBCOR and consequently the BBS. For aluminum this is achieved by developing new high-strength alloys that can be made thinner (to increase the trampoline effect) without denting. The past decade has seen the development of new composite materials that increase the barrel flexibility beyond that achievable with aluminum, giving rise to a new generation of high-performing bats.

We now turn to the MOI, which depends on both the weight of the bat and the distribution of the weight along its length. For a given weight, the MOI is largest when a larger fraction of the weight is concentrated in the business end of the bat (i.e., the barrel). The MOI affects bat performance in two ways in that both q and the bat speed depend on it. A larger MOI means a larger q (and vice versa), in complete agreement with our intuition. A heavier bat will be more efficient than a light bat in transferring energy to the ball. But, contrary to popular belief, it is not the total weight of the bat that matters but rather the weight in the barrel, where the collision with the ball occurs. That’s why it is the MOI that matters and not just the weight. But a larger MOI also means that the bat won’t be swung as fast, which again agrees with our intuition. Once again, research has shown that it is the MOI of the bat and not just the weight that affects swing speed.

The fact that the MOI affects bat performance in two opposite ways raises an interesting question. If I have two bats with the same BBCOR but with different MOI, which one will have the larger BBS? For example, if I “cork” a wood bat, which reduces its MOI, will the resulting increase in swing speed compensate for the reduction in collision efficiency? Current research suggests that the answer is “no” and that corking a bat does not lead to a larger BBS. For a detailed account, see this article. By the way, corking a wood bat does have some important advantages, even though higher BBS is not one of them. By reducing the MOI, the batter will have a “quicker” and more easily maneuverable bat, allowing him to wait a bit longer on the pitch and to make adjustments once the swing has begun. So, although corking a bat may not lead to higher BBS, it certainly may lead to better contact more often.

For bats of a given length and weight, the MOI will generally be smaller for an aluminum bat than for a wood bat. After all, a wood bat is a solid object, so a larger fraction of its weight is concentrated in the barrel than for a hollow nonwood bat. Here is another simple experiment you can do. Take two bats of the same length and weight (e.g., 34”, 31 oz), one wood and one aluminum, and find the point on the bat where you can balance it on the tip of your finger. You will find that the balance point is farther from the handle for the wood bat than for the aluminum bat, showing that a larger concentration of the weight is in the barrel for the wood bat. However, keeping in mind the corked bat discussion, the lower MOI for an aluminum bat results in no net advantage or disadvantage for BBS. The real advantage in BBS of aluminum over wood is in the BBCOR (i.e., the trampoline effect).

Let’s talk briefly about how bat performance is measured in the laboratory. Details can be found at this web site. Briefly, the basic idea is to fire a baseball from a high-speed air cannon at speeds up to about 140 mph onto the barrel of a stationary bat that is held horizontally and supported at the handle. Both the incoming and rebounding ball pass through a series of light screens, which are used to measure accurately its speed. The collision efficiency q is the ratio of rebounding to incoming speed. The MOI is measured by suspending the bat vertically and allowing it to swing freely like a pendulum while supported at the handle. The MOI is related to the period of the pendulum. Once q and the MOI are known, these can be plugged into a well-established formula to determine the BBCOR. To calculate BBS, the master formula is used along with a prescription for specifying the pitch and bat speeds, the latter of which will depend inversely on the MOI.

Various organizations use this information in different ways to regulate the performance of bats. The Amateur Softball Association regulates BBS, using laboratory measurements of q and MOI along with the prescriptions noted above to calculate BBS using the master formula. For the past decade, the NCAA has regulated baseball bats by requiring that q is below some maximum value and the MOI is above some minimum value, the latter limiting the swing speed. Together the upper limit on q and lower limit on the MOI effectively limit the maximum BBS. The maximum q is set to be the same for nonwood as for wood. The lower limit on MOI is such that the best-performing nonwood bat outperforms wood by about 5 mph. You may have seen the words “BESR Certified” stamped on NCAA bats. The BESR is shorthand for the Ball Exit Speed Ratio; numerically, BESR = q + 1/2. Starting in 2011, the NCAA will instead regulate the BBCOR, taking advantage of the fact that for bats of a given BBCOR, the BBS does not depend strongly on MOI. Moreover, the NCAA has set the maximum BBCOR to be right at the wood level, so it is expected that nonwood bats used in NCAA will perform nearly identically to wood starting next year.