| Change-Up | February 27, 2009 |

It’s preview season, folks, and we're shifting gears for 2009. We are scrapping the Two on Two format we have run the past few years. It was fun, conversational and we had some talented guests. But they were looooong and light on numbers. We're changing it up this season.

Here’s the deal. For hitters we take PECOTA and the four projection systems on Fangraphs. Fangraphs, by the way, is awesome. They are doing terrific, differentiated, value-add work and if you are a regular reader of Baseball Prospectus and/or The Hardball Times, you should add Fangraphs to your favorites as well. Anyway, we average all five of these projection systems to give you a sense for how the number crunchers see the players performing this season.

For pitchers, in the interest of keeping things simple and consistent, we go with the three projection systems readily available on the Fangraphs player pages. No PECOTA because the data presentation was not as compatible with the numbers we wanted to display.

We went with depth charts from ESPN.com. Some of the players penciled in below will not be starting, and some might not break camp. But we figured this was a pretty good way to go. As we draw closer to Opening Day with the other divisions, we will look to implement as accurate of an indication as possible with regard to who figures to start at each position.

You will then get brief commentary from me, from another Baseball Analysts contributor (today it’s Papa Bear, Rich) and then a member of the mainstream media. What’s a preview without someone who managed to emerge from their Mom’s basement?

Today we kick off with the NL East, and we are grateful to Kevin Kernan of the New York Post for participating.

Catcher

AVG OBP SLG

Ruiz, C. .253 .332 .378

Schneider, B. .249 .326 .368

Baker, J. .259 .337 .394

McCann, B. .296 .362 .506

Flores, J. .249 .306 .408

Kevin: Mets have to get some offense from Brian Schneider, who insists he is better prepared for the challenge of playing in New York this year.

Sully: The 25-year old Brian McCann is the strongest of this bunch but I will be interested to see if John Baker can build on his .299/.392/.447 stint in the Big Leagues last season.

Rich: McCann, hands down. His 2008 season was about halfway between his 2006 and 2007 campaigns. I see no reason why he won't put up similar numbers this year. In the meantime, I've got the unders on Baker repeating those rate stats as a sophomore.

First Base

AVG OBP SLG

Howard, R. .271 .369 .562

Delgado, C. .265 .350 .492

Cantu, J. .270 .321 .455

Kotchman, C. .281 .348 .431

Dunn, A. .246 .378 .506

Rich: Ryan Howard is in the prime of his career and reportedly in great shape. What's not to like? I meant with respect to Howard, not Florida's and Atlanta's first basemen.

Kevin: Over a 23 day span in September the revitalized Carlos Delgado slugged seven home runs and drove in 19 runs. Over that same stretch Ryan Howard hit 11 home runs and drove in 31 runs. Enough said.

Sully: Some announcer is going to remark in September that Jorge Cantu, with 23 home runs and 89 RBI is having "another productive year". Take it to the bank.

Second Base

AVG OBP SLG

Utley, C. .295 .376 .515

Castillo, L. .276 .354 .340

Uggla, D. .259 .340 .477

Johnson, K. .281 .362 .453

Hernandez, A. .245 .295 .337

Sully: In a division loaded with individual stars, Chase Utley remains the very best. Now 30, it will be interesting to see how long he can keep up the HOF-caliber output (with the bat and glove) that we have seen from Utley since he burst onto the MLB scene in 2005. Four second basemen have had a better OPS+ in their 26-29 seasons: Rogers Hornsby, Nap Lajoie, Eddie Collins and Rod Carew. Not bad.

Rich: If Utley is healthy from the get go, he is the class of this group, followed by Dan Uggla, Kelly Johnson, and . . . yuck . . . I'll leave it at those three.

Kevin: Draw up a second baseman that is a winner and you have Chase Utley. Jerry Manuel is trying to pump new life in Luis Castillo, saying he could bat leadoff. Utley, who is always self-motivating, is coming back from hip surgery.

Third Base

AVG OBP SLG

Feliz, P. .251 .297 .417

Wright, D. .307 .397 .536

McPherson, D. .228 .310 .439

Jones, C. .322 .420 .545

Zimmerman, R. .288 .351 .472

Sully: When you factor durability, it's hard to take Chipper Jones over David Wright but my goodness, how good is Chipper? If he can muster another excellent full season or two and steer clear of too steep of a decline phase, he has an outside chance of finishing up as the finest third baseman ever to play. Go look for yourself. It's nuts.

Rich: It is nuts. Nobody is passing Mike Schmidt anytime soon. As close as Chipper and Michael Jack are offensively, don't forget defense. Jones is a no brainer Hall of Famer but Schmidt is the best third baseman in the history of baseball.

Kevin: Look for Wright to make big-time adjustment this season as Mets are working on hitting the ball the other way in special drills designed by Manuel. Chipper is the model third baseman.

Shortstop

AVG OBP SLG

Rollins, J. .281 .343 .454

Reyes, J. .294 .355 .456

Ramirez, H. .306 .383 .524

Escobar, Y. .291 .362 .409

Guzman, C. .298 .337 .423

Sully: Not a bad one in the group, but give me the perennial MVP candidate, defensive warts and all.

Rich: Now we're talking, Sully. I love Jose Reyes but Hanley Ramirez might be the most valuable property in the game.

Kevin: Numbers don’t tell the entire story of this position. Jimmy Rollins has an inner toughness that enables him to lift his game at the most vital times. This is the Division of Shortstops. Not a bad duo for Dominican team in WBC with Reyes and Ramirez.

Left Field

AVG OBP SLG

Ibanez, R. .282 .346 .466

Murphy, D. .281 .347 .438

Ross, C. .264 .329 .483

Anderson, G. .280 .319 .433

Willingham, J. .264 .361 .466

Sully: Whereas the NL East is loaded with talent around the infield, it is much thinner in the outfield. I am unsure as to who the best left fielder in the division is, but I do not think that one of Raul Ibanez, Cody Ross or Josh Willingham should be the best at their position in any division! On a side note, isn't Matt Diaz better than Garret Anderson?

Rich: Aren't left fielders supposed to hit? I mean, really hit? Take the best batting, on-base, and slugging average and you only get .282/.361/.483. Yikes!

Kevin: Just think how much fun this division would be if Mets had signed Manny Ramirez. Look for Mets Daniel Murphy to establish himself this season.

Center Field

AVG OBP SLG

Victorino, S. .284 .345 .429

Beltran, C. .278 .366 .502

Maybin, C. .268 .332 .427

Anderson, J. .283 .329 .376

Milledge, L. .277 .345 .433

Sully: It's rare that someone joins a big market team and then becomes underappreciated but is that what we are seeing with Carlos Beltran? After his ridiculous 2004 post-season, Beltran joined the Mets and save for a lackluster first season in Flushing, has been one of the best players in baseball. He's on a HOF track.

Rich: No contest here. Beltran is the man. He's the full package, a five-tool player capable of changing games with his bat, glove, arm, or legs.

Kevin: No one has more confidence than Shane Victorino and that cannot be undersold. Beltran says his knees are healthy again. For all the money the Mets spent on Beltran, they have one playoff appearance to show for it.

Right Field

AVG OBP SLG

Werth, J. .272 .365 .468

Church, R. .266 .345 .448

Hermida, J. .271 .352 .447

Francoeur, J. .271 .319 .433

Dukes, E. .260 .366 .458

Sully: If Elijah Dukes can stay healthy and clean up his act, the sky's the limit. He's an excellent defender with a good handle on the strike zone and solid pop.

Rich: Wow, this division really is thin in the outfield. While there is some talent in this group, it's been more promise than production thus far.

Kevin: Jeff Francouer has made some big changes in his swing. If Ryan Church falters, Mets will go out and get big-time right-fielder at the trade deadline.

Starting Pitching

Philadelphia

W-L K/9 BB/9 WHIP ERA

Hamels, C. 14-8 8.42 2.35 1.13 3.36

Myers, B. 10-9 7.90 3.10 1.33 4.17

Blanton, J. 11-10 5.54 2.57 1.33 4.02

Moyer, J. 10-10 5.45 2.88 1.41 4.57

Kendrick, K. 8-8 4.44 2.87 1.45 4.81

New York

W-L K/9 BB/9 WHIP ERA

Santana, J. 15-8 8.82 2.38 1.12 3.19

Maine, J. 10-10 7.78 3.81 1.34 3.99

Perez, O. 10-10 8.56 4.55 1.42 4.34

Pelfrey, M. 10-10 5.77 3.36 1.43 4.26

Garcia, F. 6-6 6.56 2.75 1.34 4.28

Florida

W-L K/9 BB/9 WHIP ERA

Nolasco, R. 11-9 7.53 2.25 1.24 3.92

Johnson, J. 7-5 7.69 3.46 1.38 3.93

Volstad,C. 8-7 5.88 3.74 1.43 4.32

Sanchez, A. 6-6 7.29 4.04 1.43 4.32

Miller, A. 6-7 7.63 4.57 1.53 4.67

Atlanta

W-L K/9 BB/9 WHIP ERA

Lowe, D. 13-9 5.99 2.46 1.27 3.60

Vazquez, J. 13-10 8.54 2.45 1.22 3.75

Jurrjens, J. 10-8 6.73 3.28 1.36 3.93

Kawakami, K. --------

Glavine, T. 6-6 4.94 3.62 1.51 4.81

Washington

W-L K/9 BB/9 WHIP ERA

Olsen, S. 9-12 6.45 3.47 1.44 4.66

Cabrera, D. 8-10 6.83 4.63 1.52 4.81

Lannan, S. 8-11 5.68 3.63 1.40 4.27

Hill, S. 4-5 5.69 2.76 1.41 4.32

Balester, C. 6-8 6.45 3.31 1.43 4.80

Sully: Live arms and long games in Miami this season!

Rich: While the Phillies and Mets sport the two best pitchers in the division (if not the league), don't underestimate Atlanta's starters, especially if Kenshin Kawakami is as good as his breaking ball. Derek Lowe has been underrated for far too long and Javier Vazquez's outstanding peripherals are bound to result in a better ERA in the NL than the AL.

Kevin: Johan Santana and Cole Hamels will fight it out for Cy Young. Little known Hamels fact: A former Mets farmhand named Fred Westfall was Hamels first pitching coach when he was in the Carmel Mountain Ranch Little League in San Diego and was the first to begin to teach Hamels the changeup.

Bullpen

Philadelphia

K/9 BB/9 WHIP ERA

Lidge, B. 11.10 4.13 1.27 3.39

Madson, R. 7.22 2.92 1.33 4.00

Durbin, C. 6.48 3.42 1.37 4.15

New York

K/9 BB/9 WHIP ERA

Rodriguez, F. 10.86 4.01 1.21 2.91

Putz, J. 9.89 3.21 1.19 3.21

Sanchez, D. 6.94 3.51 1.35 3.94

Florida

K/9 BB/9 WHIP ERA

Lindstrom, M. 7.64 3.85 1.43 4.00

Nunez, L. 7.05 2.95 1.29 3.81

Kensing, L. 8.66 4.68 1.42 4.20

Atlanta

K/9 BB/9 WHIP ERA

Gonzalez, M. 9.41 3.91 1.28 3.43

Acosta. M. 7.07 4.97 1.48 4.26

Boyer, B. 7.85 3.89 1.45 4.49

Washington

K/9 BB/9 WHIP ERA

Hanrahan, J. 8.74 4.19 1.43 4.10

Rivera, S. 6.73 3.85 1.44 3.98

Shell, S. 7.46 3.14 1.33 4.18

Sully: Philadelphia and New York are head and shoulders above the rest of the division, at least as we look at it at this point. Bullpens are tough to predict and maybe some arms will emerge for the other teams but for now, it is the bullpen that seems to represent the biggest area of separation between the class of the division and the also-rans.

Rich: Brad Lidge was 48-for-48 in save opportunities (including the postseason) and led all relievers in Win Probability Added last season. Get this, he has averaged 12.50 K/9 over the course of his six-year career. K-Rod and J.J. are upgrades for the Mets, at least versus the post-Billy Wagner days last season.

Kevin: K-Rod t-shirt ($28) is four dollars more than David Wright t-shirt. Omar has put his money in the bullpen to try to match up with Lidge after Mets blew 29 saves in 2008.

Bench

Sully: I like Philadelphia's bench. Ronny Paulino might help, and Geoff Jenkins could bounce back and once again pound on righties the way he had his whole career.

Rich: The benches don't look all that great to me. Look for a late free agent signing or a rookie (Jordan Schafer?) making the difference here.

Kevin: Phils seem to understand this concept better than most teams.

Who are the awards candidates from the NL East?

Kevin: The MVP and Cy Young will come out of this division, Hamels or Santana. Reyes will be in the MVP race.

Rich: Kevin may be right. The MVP and Cy Young winners could very well come from the NL East. I'd like to see Utley get his due, but I think the Mets third baseman has all the Wright stuff this year. If the Cy Young Award winner emerges from this division, look for Hamels to nab his first or Santana his third. However, Ricky Nolasco's K-BB-GB rates were just as good as those put up by Hamels and Santana last year, and there wasn't a better pitcher in the league from June 10 - through the end of the season.

Sully: There are some obvious ones in Philadelphia and New York but how about Hanley or Chipper? Hanley may need the fish to surprise to get any attention and Chipper will have to defy the medical odds but I think both are MVP caliber talents.

Any surprises this year?

Sully: Rich alluded to this above, but I think Atlanta's starting pitching allows them to hang around deep into the season.

Rich: Uggla gets traded in July and winds up in the postseason.

Kevin: Mets will not choke.

Predictions?

Rich: I will be shocked if the Phillies or Mets don't wind up on top this year. The club that finishes second will win the wild card. Let's say, Mets, Phillies, Braves, Marlins, and Nationals with Florida closer to third than fifth.

Kevin:

1. Mets

2. Phils (wild card winner)

3. Atlanta

4. Florida

5. Nationals

Sully: Well isn't this boring? I think I am with both of you guys here. That looks right to me.

Thanks, Rich and thanks especially to Kevin! Until next Friday...

| Saber Talk | February 26, 2009 |

The Rule 4 draft is, without question, one of the most important events of the year for Major League teams. One great draft can change the future of a franchise. The draft gives teams an opportunity to acquire young, talented players for a relatively small financial commitment. If one of them reaches the bigs, and becomes even an average player, you’ll garner yourself a ton of value over that player’s first six years.

Naturally, then, the draft, and studying the amateur players, is a major part of each organization’s yearly workload. Consider this response from Chris Long, Padres’ Senior Quantitative Analyst, in an interview with us last year:

What's so amazing about the baseball draft, and I'm sure the draft in other sports, is the sheer number of players to consider. Different ages, sizes, polish, playing environments, growth potentials, levels of competition faced, ability components, injury tendencies, and it goes on. Then there's the information you get from the scouts. Which scouts are better? Are they looking at the right players, in the right way, the right number of times? What's the best way to integrate all of the information you have? Overlaying all of this are considerations of finance, utility, need, risk and the poker game of the actual draft. Draft the right player and he could be worth $50 or even $100 million in value to your club (see Pujols). Draft the wrong players and you'll waste millions and negatively impact your club for years. It's an extremely difficult, messy, noisy, and thoroughly insane problem to work on. It's beautiful.

We all know about scouting. It's crucial to the game, especially in college and high school, and it isn't going anywhere. But a more unexplored area (at least on the 'net), and perhaps an equally important one, is the thorough analysis of college statistics. Many times, people will bring up what Chris brought up in the above passage, saying there are too many factors to consider, too much noise in the data. There's varying levels of competition, parks, player aging, limited sample sizes, switching from aluminum bats to wood, etc. It goes on and on.

They are, of course, right on the money. Looking at the raw stats of two college players is probably a hapless endeavor. Let's look at a quick, made-up example:

Player A: .300/.480/.680

Player B: .280/.420/.600

They are somewhat close, but if that's all we know about each player, we’ll probably go with Player A every time. But, let's say Player B played against the third-toughest opponents in Division 1 and also played in a big pitcher's park. Player A played in a small conference, against relatively weak competition, and a great hitter's park. Now who are you goin' with? And not to mention, this is a simplified example, which leaves out many significant factors. But it just serves as a reminder that the numbers, alone, are just numbers; they have relatively little utility in sorting out baseball players on the college level.

Anyway, as you can see, the reservations people have about college stats are real. However, there's no reason why we can't try to make some adjustments, and make some sense of the madness.

We've spent the last four months importing and adjusting collegiate baseball statistics in an attempt to neutralize the numbers to allow for cross-conference comparisons. To do this, we've discovered that Boyd's World is an invaluable tool. He gets much of the credit for accumulating a lot of the data and making it available online.

Now, our methods were actually pretty simple. We're judging the players in our system on a few things that we feel are a solid scope for the offensive skills necessary to succeed in professional baseball. They include:

- Weighted On-Base Average (wOBA)

- Isolated Power (IsoP; slugging percentage minus batting average)

- Strikeout percentage (K%; strikeouts divided by plate appearances)

- Walk percentage (BB%; walks divided by plate appearances)

- Speed score

All of the above are pretty self-explanatory, especially with the Wins Above Replacement explosion that happened in November and December of 2008 around the sabermetric blogosphere. However, the wOBA formula we used did not include stolen bases. Honestly, it wasn't for any particular reason, we just happened to grab the one copy of the formula that did not include it.

As for speed score, it's measuring "baseball speed," or, at least, that's the intended goal. It's actually a fairly generic speed score that is not much unlike the one Bill James used in his earlier works.

But, what do we take into account when adjusting these numbers? For us, it was park factors and level of competition faced. Those two components can vary from team-to-team in such a dramatic fashion that you'd initially swear they aren't right. For instance, Air Force had a 4-year park factor from 2005-2008 of 145. Conversely, a school like Longwood University had a park factor over that time of just 72. With such drastic discrepancies, it was important to address this. Again, drawing from Boyd's World, we have multiple-year park factors. He lists two for each team, one being a PF and one being TPF – or Park Factor and Total Park Factor. The former is just rating that team's home park, while the latter is rating all of the parks that team played in over the course of time it was tracked. So, Air Force's 145 park factor is just their home park. Playing in the Mountain West, they frequent some of the most hitter friendly parks in collegiate baseball, and their Total Park Factor was 128 from 2005-08. Basically, over those years, Air Force's team played in environments that were 28 percent more offense-friendly than a neutral ballpark, which would have a rating of 100.

To neutralize for park factors, we take the wOBA for each hitter, and simply run it through this: wOBA*square root(100/Total Park Factor). This nets us a Park-Adjusted wOBA (PAwOBA).

But that's just the first part of the components to neutralize. You also have to take into account the competition these numbers are being tested against. As mentioned previously, two stat lines, unadjusted, are not equal. Thankfully, Boyd's World comes through again with his Strength of Schedule ratings. To neutralize this, we do pretty much the same from above.

PAwOBA*square root(Strength of Schedule/100)

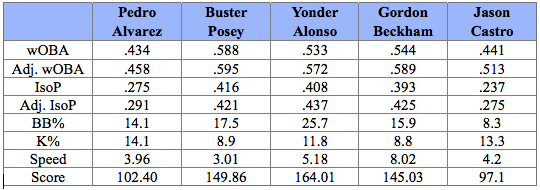

This gets us a wOBA for the players that are now both park and competition adjusted. We do this for IsoP's as well, using the same methods just substituting IsoP for the wOBA's. And before we jump straight to the table (even though this is going on long enough), we'd like to give a brief introduction to our "Score" category. We don't have a catchy name for it yet (although we're open to all suggestions), but what it encompasses is all of the categories that we're tracking. It weights the adjusted wOBA's, adjusted IsoP's, K and BB% and throws in our speed score, as well. But, we've rambled enough. On to the 2008 stats for the first five college bats taken in the 2008 Rule 4 draft:

A note on speed score: It's scaled down so it goes as such: -5 is terrible, 0 is bad, 5 is average, 10 is good, 15 is great, 20+ is flat-out burner.

The above are nothing more than just the 2008 numbers for the first five college bats taken last June. They are not meant to be a predictor of talent moving from aluminum to wood bats. Instead, it's just, at the moment, adjusting to see who had the best statistical seasons when you account for who they were playing and where. When the 2009 draft comes around, we'll have a better tool to judge player performance than just the raw stats, and hopefully it will shed some light onto who the top prospects are.

Also, don't forget that we haven't considered positional values or defense. A player's position is very important at this level. Players that start on the left of the spectrum (1b, left field, right field) have to hit a ton to make it in the bigs. Most great prospects start on the right side of the spectrum as amateurs and gradually shift to the left as they age, provided that their bats can play at those less-demanding defensive positions.

Additional Resources

Earlier in the article, it was mentioned that this type of stuff has been somewhat unexplored on the Internet. While that may be the case, there's certainly been plenty of research into the area:

- Right here at Baseball Analysts, Kent Bonham did some very similar work back in 2006.

- Jeff Sackmann, partnering with Bonham, runs collegesplits.com. He also does great work at The Hardball Times, much of it focusing on the college game and its numbers.

- This post at Sons of Sam Horn details how to go about some of these adjustments.

- Lincoln Hamilton, at Project Prospect, has also done some similar analysis.

| Change-Up | February 25, 2009 |

"I had a friend who was a big baseball player back in High School." - Bruce Springsteen

I played high school baseball with three players who went on to play at Princeton University and others who played at smaller, Division 3 schools such as Brandeis, Williams College and Trinity College. I faced Big Leaguers Rich Hill, Mike Smith and Jonah Bayliss and was invited to participate in regional combines and team tryouts like the Area Code Games. All in all, I think I was exposed to some decent baseball.

But Jesus of Nazareth, I could not imagine facing the Long Beach Poly baseball teams of the mid 1990's with one potential future Hall of Famer, Chase Utley, and another standout, Milton Bradley, who is coming off a 163 OPS+ season. Bradley was taken in the second round of the 1996 Amateur Draft and signed immediately with the Montreal Expos. The Dodgers selected Utley in the 2nd round the very next season but Utley chose to go to UCLA instead of signing. Since, Bradley has shown flashes of greatness when he could stay on the field while Utley has had a steadier developmental timetable. He was never truly spectacular until his breakout 2005 campaign. Since, he's been as good as most any other second baseman in baseball history.

There have been other notable, productive high school teammate combos in the Major Leagues. Jason Giambi and Jeremy Giambi played alongside the late Cory Lidle, Shawn Wooten and Aaron Small at South Hills High School in West Covina, California. That's right, FIVE Major Leaguers on one high school team. Recent first rounders Mike Moustakas and Matt Dominguez played on the same team at Chatsworth High School; they were the first pair of position player teammates to be drafted in the first round since 1972, when Jerry Manuel and Mike Ondina were taken out of Rancho Cordova High School in California. High School teammates were also selected in the first round in 2002 (Scott Kazmir among them), 2000 and 1997 (including Michael Cuddyer).

Now, however, there is a new premier duo ready to take their talents to the Bigs. Baseball America released their top-100 prospects yesterday and numbers 1 and 23 batted 3 and 4 for Stratford High School in Goose Creek, SC. Matt Wieters is a 23 year-old, switch-hitting catcher who has hit .355/.454/.600 in his brief Minor League career. He might be the best player in the American League right now. Justin Smoak hit .304/.355/.518 in a brief Minor League stint after being drafted by the Texas Rangers last year but to give you a more complete sense for his potential, he is a former Cape League MVP who hit .383/.505/.757 in his final year playing for the University of South Carolina Gamecocks. Both should be contributing to their respective Major League teams this season.

Gregg Zaun currently stands in Wieters's way as the Baltimore backstop, but that won't last long. Wieters will be starting for the majority of the year. The path for Smoak is a little less clear. Chris Davis has earned a shot as the starting first baseman and Texas has moved veteran Hank Blalock to designated hitter. Smoak stands to begin the season down on the farm but will get his chance at one point or another. He will have to make the most of it if he wants to stick for good at the outset.

What I am interested in is some of the high school teammates that I am missing. Who are the best high school teammates to come out of your local area? Are there other Major Leaguers who played high school ball together going back further that I am not considering? Please feel free to share in the comments section.

| Touching Bases | February 24, 2009 |

With apologies to Dave Studeman, whose batted ball leaderboards on The Hardball Times are always must reads, I decided to try a similar data presentation, breaking up batted ball stats by fields of play instead of by type. Using linear weight run values, I developed lists showing who the most productive players were in 2008 when pulling the ball, taking the ball back up the middle, or going to the opposite field.

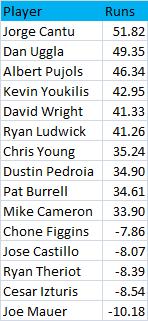

Value of Pulled Batted Balls

Every one of the top ten players when it came to pulling the ball happened to bat right-handed, which can be explained by their relative advantage when hitting ground balls. Righties who pull grounders force longer throws than lefties who pull grounders. These players are mainly fly ball hitters. In the case of switch-hitters like Chone Figgins, I combined their pulled/center/opposite field stats from each side of the plate, so right-handed balls to left are added to left-handed balls to right to come up with pulled batted balls.

Jorge Cantu and Dan Uggla—who would’ve thunk? Uggla is a former Rule 5 pick and Cantu spent time last year in two different minor league systems before both found their rightful spots on the Marlins. I’d have to attribute their appearance on the leaderboard to coincidence. Dustin Pedroia and Kevin Youkilis, on the other hand, are given a bit of an extra push, as both are clearly aided by the green monster. Pedroia might be the perfectly suited player for Fenway. Just check out his home run chart. He has yet to hit a 400-foot homerun in his career. You have to wonder whether he’d be the MVP outside of that park, as it would certainly be a challenge to find a voter who checks park-adjusted stats.

I don’t think I ever expected to see the universally beloved Joe Mauer on the bottom of any list, but he gets murdered by pulled groundballs. Only three of his nine long balls went to right field in 2008, as he unfortunately never developed the 20 homerun power people were hoping for. Chone Figgins, Ryan Theriot, and Cesar Izturis all had one homerun apiece last year, while Castillo tallied six, so it appears that a minimal amount of power is necessary to be successful pulling the ball.

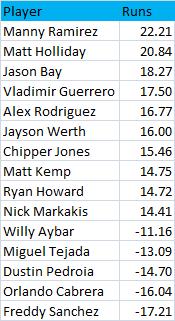

Value of Center Field Batted Balls

It’s interesting that the top six players on this list bat right-handed. But the bottom four players do too, so that would suggest that the trend of righties is random. It’s tough to choose between the hitters best at pulling the ball and best at going up the middle, but I’m siding with the latter set of players. I’d classify the first set of hitters more as homerun hitters and the second set as line drive types. Pedroia appears at the bottom of this list, likely because in Fenway he doesn’t derive the same benefit from his fly balls to center as he does to the left-field wall. He picked up just three hits on 73 center-field flies.

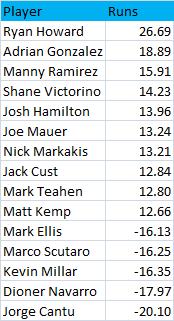

Value of Opposite Field Batted Balls

What Mauer lacks in pulled balls he makes up for with his approach going the other way, as he is the only catcher to appear on a leaderboard. Nick Markakis, Matt Kemp, and Manny Ramirez all show up as top center and opposite field hitters. These guys are at times described as "pure" hitters, and there's why. I'd presume each one is quite talented at going with the pitch.

Without trying to sound hyperbolic, I have to ask: is Ryan Howard the greatest opposite-field power-hitter ever? His 2006 and 2008 seasons in which he crushed 25 and 20 opposite-field blasts, respectively, are the only years in the last four in which any player has hit more than even 15 homers to their weak side. Howard does have his opposite-field numbers skewed by his groundball run value, which is likely only positive due to the vacated side of the infield.

Analyzing Howard’s trends piqued my interest in a specific batted ball type and location: pulled groundballs. There were seven players who cost their team 20 runs on pulled grounders: Mark Teahen, Prince Fielder, Adrian Gonzalez, Ryan Howard, Jimmy Rollins, Casey Kotchman, and Carlos Delgado. Several of these players do indeed receive the defensive shift, but I immediately noticed one of these names is not like the other. Jimmy Rollins sticks out like a sore thumb. He’s a switch-hitter, and as such is the only non-lefty to appear on the list. He is far and away the fastest player in the group and an absolutely awesome baserunner, but he apparently wasn’t able to make the most of his speed last year when he put the ball in play, compiling a well below league average 19% hit rate on grounders and legging out a single bunt hit in seven attempts.

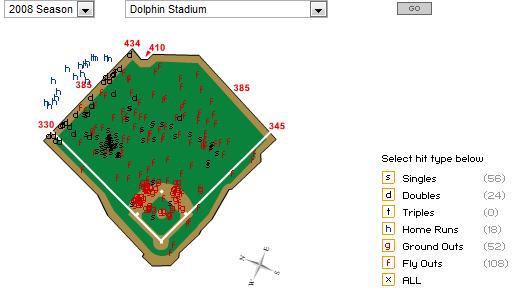

Adrian Gonzalez might actually have power that approaches Howard’s but we’ll never know until he gets out of Petco. At the other end, one thing’s for certain: pitchers need to find ways to prevent Cantu from pulling the ball. Here's what the spray chart for Cantu—perhaps the best pull hitter and worst opposite field hitter in the game—looks like.

| Baseball Beat | February 23, 2009 |

The 2009 salary arbitration process, which was collectively bargained and implemented in 1974, has come and gone with the players making out just fine. Of the 111 players who filed for arbitration last month, 65 settled prior to exchanging salary figures, 43 negotiated contracts after submitting numbers, and only three cases were heard by arbitration panels (with the players winning two and losing one).

Florida Marlins second baseman Dan Uggla won his arbitration case and will make $5.35 million rather than the $4.4 million the team offered. Washington Nationals righthander Shawn Hill was awarded his asking price of $775,000 instead of the $500,000 submitted by the club. Tampa Bay Rays catcher Dioner Navarro, on the other hand, lost his arbitration case and will make $2.1 million rather than the $2.5 million he was seeking. Don't feel too badly for Navarro as he will still pull down $1,667,500 more than the $432,500 he earned in 2008.

Maury Brown of The Biz of Baseball has compiled all of the vital stats. According to Maury, the average year-over-year increase in salary for the 111 players who filed was a "whopping 751 percent."

As Fred Claire observed, "The arbitration-generated salaries are in sharp contrast to what has happened in this year's free-agent market where a number of high-profile players have had to sign contracts far below their expectations and a number of other 'name' players remain on the sidelines without contracts."

What was of interest to me were the number of contracts that were negotiated at or near the midpoint with little interest on the part of players and owners to "win." I put together a list of ten first-year eligible position players who signed one-year contracts earlier this month to avoid salary arbitration with the objective of analyzing these deals. There were several others who avoided arbitration by signing longer-term agreements. The latter transactions are much more difficult to compare than the relatively simple and straightforward one-year deals.

Before we get too far ahead of ourselves here, I thought it would be instructive to review the ins and outs of salary arbitration. The Major League Baseball Players Association provides the following primer on its website.

Q: When does a player become eligible for salary arbitration?A: A player with three or more years of service, but less than six years, may file for salary arbitration. In addition, a player can be classified as a "Super Two" and be eligible for arbitration with less than three years of service. A player with at least two but less than three years of Major League service shall be eligible for salary arbitration if he has accumulated at least 86 days of service during the immediately preceding season and he ranks in the top 17 percent in total service in the class of Players who have at least two but less than three years of Major League service, however accumulated, but with at least 86 days of service accumulated during the immediately preceding season.

The details of the ten negotiated contracts referred to above are provided in the following table, along with positions, ages, major league service time, and career batting (AVG/OBP/SLG/OPS+) and fielding (Ultimate Zone Rating per 150 games) rate stats:

POS BORN ML SERV CONTRACT AVG OBP SLG OPS+ UZR/150

Andre Ethier RF 4/10/82 2.153 $3.100M .299 .364 .482 116 0.1

Jeff Francoeur RF 1/08/84 3.088 $3.375M .268 .312 .434 92 9.6

Corey Hart RF 3/24/82 3.038 $3.250M .277 .323 .485 106 -0.5

Conor Jackson LF 5/07/82 3.067 $3.050M .287 .367 .443 105 11.5

Mike Jacobs 1B 10/30/80 3.047 $3.250M .262 .318 .498 110 -8.6

Kelly Johnson 2B 2/22/82 3.127 $2.825M .273 .356 .440 108 -9.1

Ryan Ludwick RF 7/13/78 3.109 $3.700M .273 .345 .512 122 10.3

Rickie Weeks 2B 9/13/82 3.131 $2.450M .245 .352 .406 97 -10.9

Josh Willingham LF 2/17/79 3.123 $2.950M .266 .361 .472 117 -6.0

Ryan Zimmerman 3B 9/28/84 3.032 $3.325M .282 .341 .462 110 10.0

The average contract calls for a 2009 salary of $3,127,500. Ryan Ludwick ($3.7M) received the highest amount of money and Rickie Weeks ($2.45M) the lowest with the other eight tightly bunched in a range of $2.95M (Josh Willingham) to $3.375M (Jeff Francoeur).

Although Andre Ethier only had 2.153 years of MLB service, he was eligible for arbitration as a "Super Two." Ethier ranks first in AVG, second in OBP, fourth in SLG, and third in OPS+, yet agreed to a deal that was only the sixth highest overall and last among his peers in right field. This one looks like a better deal for the Dodgers than Ethier.

Francoeur and the Braves agreed to a salary that was exactly in the middle of the figures that were exchanged ($3.95M and $2.8M). He has the worst OBP and OPS+ of them all despite manning a corner outfield position. He is the second-youngest player in the group but that is neither here nor there when it comes to salary arbitration. He is one of the most overrated players in baseball and his contract is a huge win for him and a disservice to the arbitration process.

Corey Hart re-signed with the Brewers for the average of what each side wanted ($3.8M and $2.7M). No performance bonuses were attached to the deal. Hart's stats pale in comparison to Ethier but his back-to-back 20 HR/20 SB seasons give his numbers more sizzle in an arbitration hearing than his similarly aged counterpart. I would call this one a fair deal for both sides.

Like Hart, Conor Jackson and the Arizona Diamondbacks reached a settlement that split the difference between what each side submitted ($3.65M to $2.45M). There were no performance bonuses. His UZR rating in left field is based on a small-sample size, and it is still possible that he could end up at first base (where he sports a -3.5 UZR/150 games rating) if Eric Byrnes is healthy and productive enough to win back his job in left. Let's call this one a draw.

Mike Jacobs signed with the Royals at a price ever so slightly below the mid-point of what he asked for ($3.8M) and what the club offered ($2.75M). The first baseman can make up the gap of $25,000 by being named to the All-Star team. He has the second-highest SLG but plays a position that demands power, especially when one doesn't get on-base more often or contribute in a more positive manner defensively. When KC acquired him, I figured he wouldn't make more than $3M in arbitration. I stand corrected and believe his contract is a bit on the high side given his overall production.

Kelly Johnson and the Braves met at the halfway point of their submissions ($3.3M and $2.35M, respectively). The second baseman can earn $50,000 if he reaches 620 PA and another $25,000 for 670 PA. At best, Johnson can make $2.9M, which would be the second-lowest agreed-upon salary in this group. I believe this deal is the opposite of Francoeur's — a good one for the team and a bad one for the player. If anything, this contract is another in a long line of examples where second basemen are treated unfairly by the system.

The gap between the Cardinals offer ($4.25M) and Ludwick's asking price ($2.8M) was the largest in this sample. It appears as if St. Louis tried to lowball him initially because he wound up receiving a salary that was much closer to his side plus the following performance bonuses: $25,000 each for 625 and 650 PA and an additional $50,000 for 675 PA. Ludwick ranks first in career SLG and OPS+ and is coming off the best season, by far, of any of these players. However, he was rewarded handsomely for his contributions.

Weeks and the Brewers avoided arbitration by agreeing to a $2.45M deal, which was just above the mean of what each side submitted ($2.8M and $2M). Weeks can also earn the following performance bonuses: $25,000 each for 575, 600, 625, 650 PA although it should be pointed out that he has never reached any of those levels in a four-year career that has been marred with injuries and disappointments. It looks like a fair deal based on actual performance but potentially a smart one on the part of the team if Weeks finally fulfills his promise.

Willingham signed with the Nats at a price below the mid-point of the salary ranges ($3.6M-$2.55M). He will earn $25,000 at each of the following plate appearance totals: 525, 550, 575, 600. All told, Willingham can make $3.050M in salary and bonuses, which is just below the average of what each side submitted. His contract is lower than any other outfielder and appears to favor the team slightly more than the player.

Ryan Zimmerman was re-signed by Washington exactly between what the Nationals offered ($3.9M) and what the player submitted ($2.75M). He will receive the following performance bonuses: $75,000 for 500 PA and an additional $50,000 each for 550 and 600 PA. If he reaches 600 plate appearances, Zimmerman will make $3.5M in salary and bonuses. Zimmerman has the fourth-highest career OPS+ and is undoubtedly the best fielder in the peer group at one of the most challenging positions. This is a deal that will most likely pay off for both sides should the youngest player earn his performance bonuses.

| Baseball Beat | February 21, 2009 |

"It's a beautiful day for a ballgame... Let's play two!"

- Ernie Banks

Is there anything better than a doubleheader? In February, mind you?

Well, my brother Tom and I attended two college season openers yesterday. Two games. Two ballparks. Two of the top-ranked prospects in the country and two of the best pitching performances on the opening weekend of the year. All in all, it was a beautiful day, one that Mr. Cub would have loved.

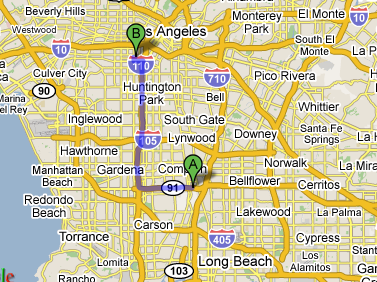

The first game of our day/night doubleheader matched San Diego State against Bethune-Cookman at the Major League Baseball Urban Youth Academy's Collegiate Baseball Tournament in Compton. The second contest was the opener of a three-game set between Long Beach State and the University of Southern California at Dedeaux Field.

The first game of our day/night doubleheader matched San Diego State against Bethune-Cookman at the Major League Baseball Urban Youth Academy's Collegiate Baseball Tournament in Compton. The second contest was the opener of a three-game set between Long Beach State and the University of Southern California at Dedeaux Field.

Tom and I were joined by general managers, scouting directors, area scouts, and agents in making the 15-mile, 25-minute trip from Compton College to USC. Of the nearly 1,000 fans at each of the two games, approximately 5 percent were employed by MLB teams.

Come the draft in June, we may look back and say there were closer to 6 percent. Scratch that. Not June. But August. You see, Scott Boras represents Stephen Strasburg and Grant Green, who just may go 1-2 in the draft. If not for the weak economy, I could see Boras asking eight figures for Strasburg, the first college player to be named to the U.S. Olympic team since the decision was made to use minor leaguers beginning in 2000.

Boras, whose son Shane is a freshman infielder for USC, was at the evening game. The agent must have been in a great mood after getting the lowdown from one of his scouts on Strasburg's pitching performance earlier that afternoon. While not perfect, the 6-4, 220-pound righthander was dominating, striking out 11 of the 23 batters he faced without allowing an earned run over 5 2/3 innings while leading the Aztecs to a 6-3 victory over the Wildcats.

IP H R ER BB SO

Strasburg 5.2 3 1 0 2 11

Strasburg's fastball lit up the radar guns. While a couple of scouts had him at 100 in the first inning, his gas was sitting at 96-99 from the windup and 93-96 from the stretch all afternoon. His curveball, which is more of a tight-rotation slurve than a 12-to-6 drop, was 79-81, a few mph below his normal 81-84 range according to a scout who has followed him closely. Strasburg's breaking ball didn't have as much depth as you might like, especially when he released it away from his body, but it is an effective companion to his heater.

If Strasburg's fastball is a "plus plus" or a 75/80 on the 20-80 scale that scouts use, his curveball was more like "solid average" or a 55 on Friday. He experienced occasional problems in landing his front foot correctly, causing him to be a bit off balance when throwing his slurve.

As for a third pitch, Strasburg didn't show much. Out of 103 pitches, the 20-year-old junior threw his changeup one time. ONCE. As in one more time than zero and one less time than two. At 88 mph, it's a pitch that many major leaguers would welcome as their fastball. The one scout would like to see him throw it more often and another scout I spoke to told me that it "looked good in the bullpen" before the game.

Aside from the 11 Ks, Strasburg induced four groundball outs and two opposite-field flies to left. He hit one batter, walked two more, and gave up three hits: a first-inning double, a grounder that was pulled just inside the third-base line on a well-located curve below the knees; an infield single to lead off the third that could have gone either way; and a run-scoring single to right field in the sixth, which was the last pitch he threw before being taken out of the game by manager Tony Gwynn.

Strasburg is undoubtedly a special talent and only a major injury or unreasonable bonus demands will keep the Washington Nationals from drafting him No. 1 in the MLB Draft in June.

After getting our fill of one "burg" in the day game and knowing we were going to be watching a "berger" (as in USC RHP Brad Boxberger) in the nightcap, Tom and I opted not to get a hamburger between games and instead settled for prime rib sandwiches at Quizno's. We took the 91 freeway to the 110 and avoided traffic – not bad for rush hour on a Friday in Los Angeles – until a few exits short of our destination, arriving in plenty of time to snag seats in the second row directly behind home plate.

We were treated to another superb pitching performance, one that looked every bit as outstanding as Strasburg's in the box score but not quite up to the same level from a scouting perspective. Not to be outdone, Boxberger allowed just one hit and no runs while striking out a career-high 11 batters en route to USC's 5-3 victory over Long Beach State.

IP H R ER BB SO

Boxberger 6.0 1 0 0 6 11

Boxberger was most impressive in the first inning when he struck out the side after allowing the first two Dirtbags to reach base on a walk and an infield error. His fastball was electric in the opening frame, hitting 92-94, but quickly dropped to 90-92 in the second, and sat mostly in the 80s thereafter.

The 20-year-old junior whiffed two more batters in each of the next three innings (although only one of the three non-strikeouts was put into play as the other two were recorded on runners attempting to steal second base), running his K total to nine through four innings. He failed to punch anybody out in the fifth but nailed two more in the sixth to give him 11 for the evening.

Boxberger not only had a combined 17 strikeouts and walks but found himself in several 3-and-2 counts, throwing a total of 123 pitches on the night. However, the 6-2, 200-pounder came up big when needed, overpowering the opposition's slow bats and keeping them just enough off balance with his slider and curve. An area scout who pitched in the majors during the 1990s told me that Boxberger "probably needs to choose one or the other because you need a lot of feel to throw both."

Unless Boxberger can build up his arm strength, he might make a better reliever than a starter. If so, it wouldn't be the first time that he was asked to pitch out of the bullpen. He was the closer for the Chatham A's of the Cape Cod Baseball League last summer, appearing in 19 games and recording nine saves while striking out 28 without allowing a home run in 18 2/3 innings. Boxberger has good bloodlines as his father went 12-1 with a 2.00 ERA and was named the Most Valuable Player of the 1978 College World Series in leading the Trojans to a national championship.

Robert Stock, a junior who doubles as the starting catcher and closer, went 2-for-3 with a walk, threw out two runners (one in which he made a quick release and great throw after backhanding a pitch) and tossed a perfect ninth (while hitting 90-91 on the radar gun) for his first save of the season. The 6-1, 190 LHB/RHP cranked a double to right-center to lead off the bottom of the second inning and lined a single to left on a curveball from a southpaw that was on the outer half of the plate in what can only be described as a nice piece of hitting. His only out was another liner to left that looked like a hit upon contact but was run down.

Stock, who skipped his senior year in high school and just turned 19 three months ago, hasn't fulfilled the lofty expectations placed upon him since being named Baseball America's Youth Player of the Year in 2005. He has hit .248 (59-for-238) with only 14 XBH in two summers in the Cape for the Cotuit Kettleers. But it is important to remember that Stock is still young and has always played against older competition. This just might be the year that he breaks out.

The main disappointment of the day was watching Green go hitless in four at-bats while striking out three times, twice looking. The 6-3, 180-pound shortstop was fit to be tied, perhaps trying to do too much in his debut. He swung and missed with a pronounced upper cut on several hittable pitches and took a few others that were in the strike zone but not in his wheelhouse. With USC pitchers striking out 15 and nailing two trying to steal, he didn't have a lot of activity in the field but made a nice play ranging to his left on a chopper over the mound.

A scout sitting in the row behind us said Green "doesn't look as strong as he did in the Cape" (when he hit .348/.451/.537 and was among the league leaders in most offensive categories) and believes he's not as physical as Troy Tulowitzki, a comparison that I mentioned after watching him make his collegiate debut two years ago and others have made as well. He likes his hands and thinks Green can stick at shortstop in the pros, yet seemed unconcerned because the only thing that could keep him from manning that position is getting too big, which wouldn't necessarily be the worst thing in the world.

The USC-Long Beach State weekend series will resume tonight at 5 p.m. at Blair Field while San Diego State faces Southern University in the MLB Urban Youth Academy Tournament at 6:00 p.m. The latter game will be televised live on the MLB Network. I'm going to the Trojans-Dirtbags contest and will be in my seat in time to see actress Sandra Bullock, who lives with her husband Jesse James in nearby Sunset Beach, throw out the first pitch.

Update: Sandra Bullock and the Long Beach State hitters pulled a no-show on Saturday night as the Trojans shut out the Dirtbags 4-0 in the second game of the weekend series before a record crowd of 3,342 at Blair Field.

| Baseball Beat | February 20, 2009 |

If you're not a stathead, fantasy geek, or a baseball nerd, then you might want to skip ahead to the rankings of pitchers in the middle and at the bottom of this article. Or you just may want to skip this article altogether and check out Deadspin, the Onion, or read the latest story or opinion on Alex Rodriguez and his cousin.

You see, I've been sorting and manipulating spreadsheets on the computer in my parents' basement (kind of embarrassing when you're 53) for the past several days. However, I'm not only planning on seeing the light of day this afternoon, I will be one of the fortunate souls who will attend two season openers today: Stephen Strasburg and San Diego State are facing Bethune-Cookman at 2 p.m. PT at the MLB Youth Academy in Compton and the Dirtbags are meeting the Trojans at 6:30 p.m. at Dedeaux Field on the campus of USC. I'll be sure to trade in my pajamas and green eyeshade for a pair of jeans and a Long Beach State (my hometown team) and USC (my college) baseball caps.

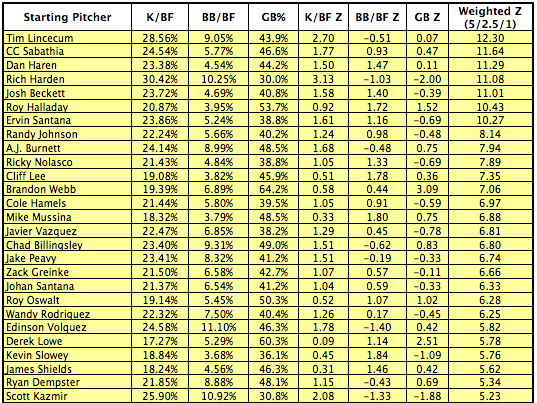

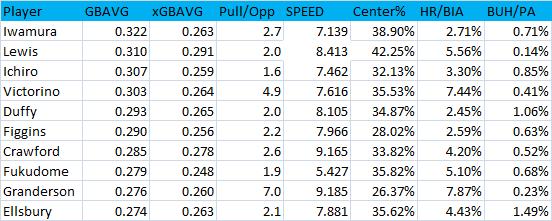

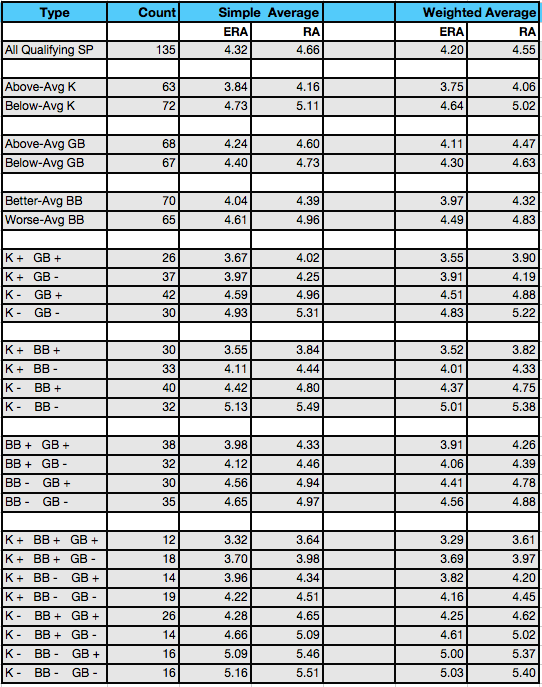

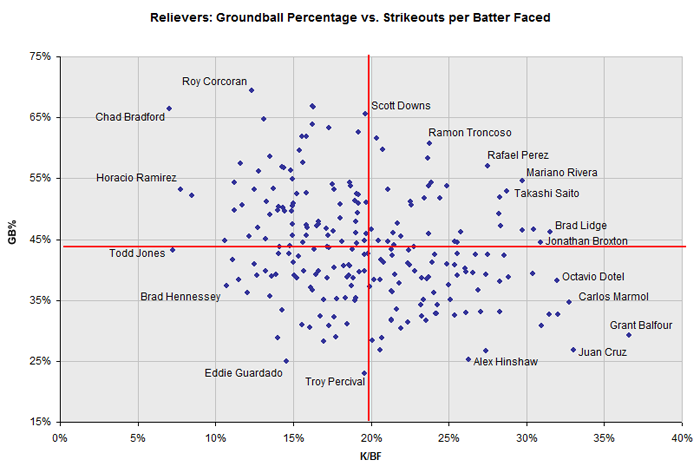

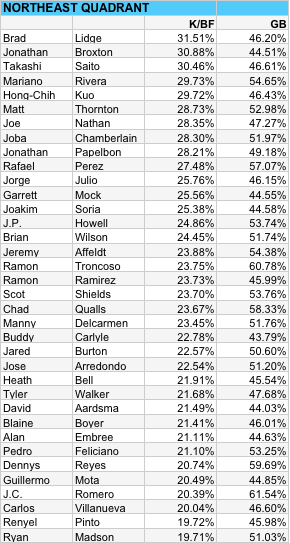

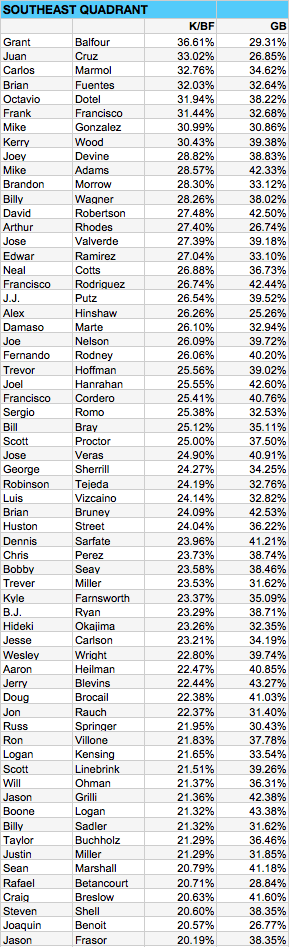

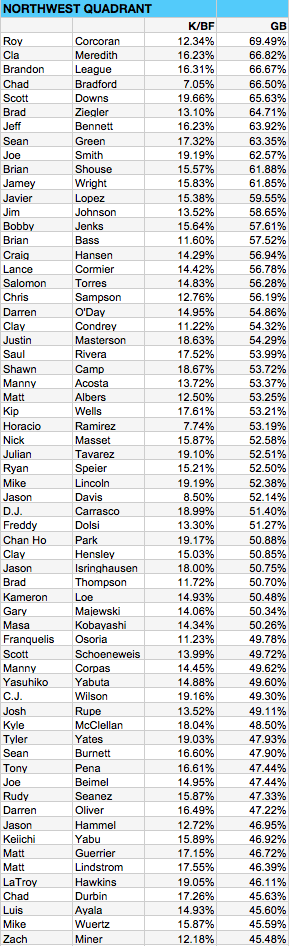

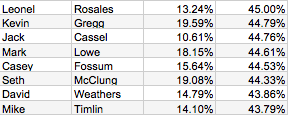

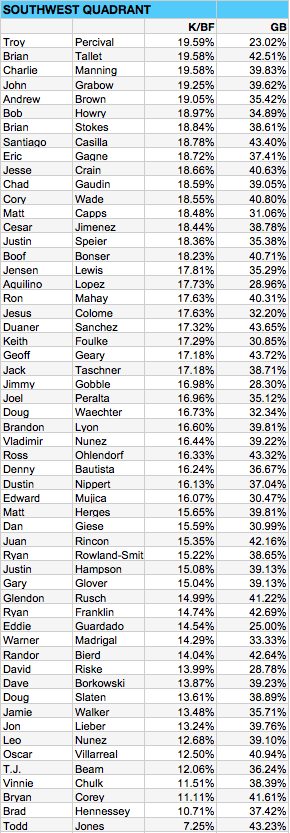

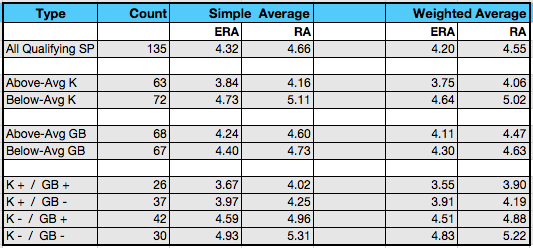

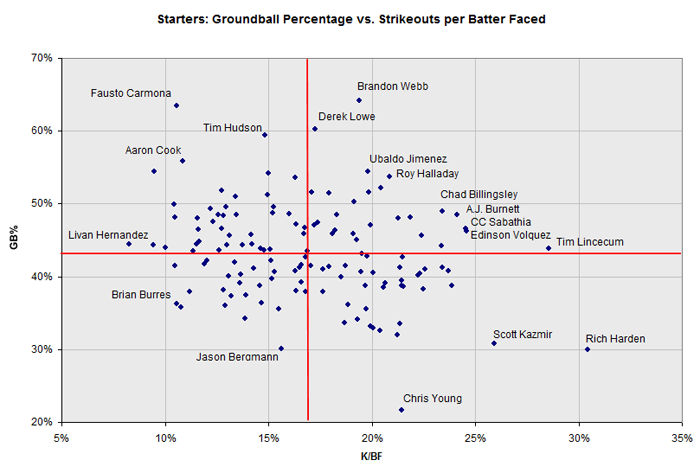

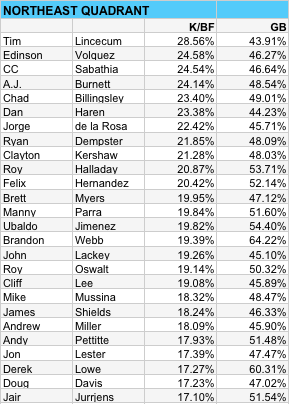

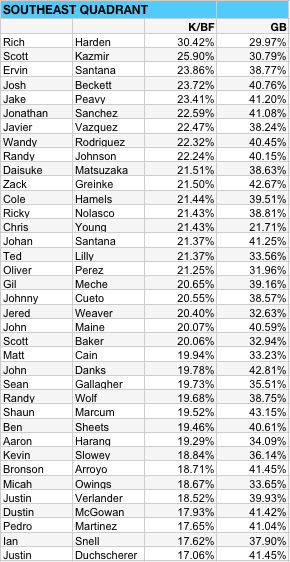

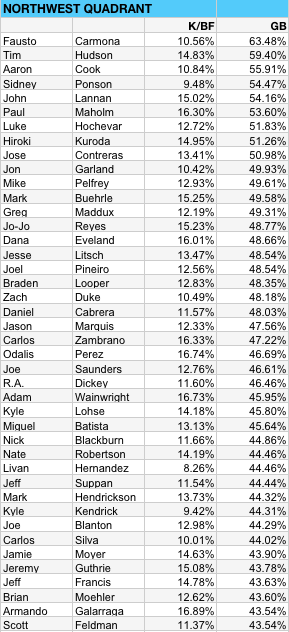

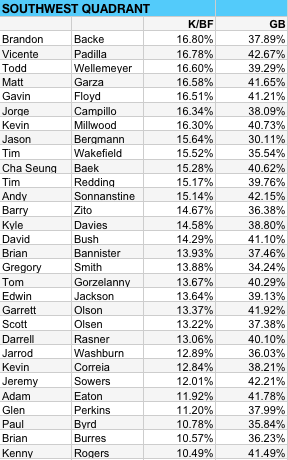

In the meantime, thanks to loyal reader and baseball enthusiast Ryan Thibodaux, I have developed a system to rank pitchers based on their strikeout, walk, and groundball rates. I had categorized pitchers by K and GB rates last week before adding BB to the mix earlier this week. The K and GB rankings were grouped in quadrants while the K-BB-GB rankings were presented in eight different sets.

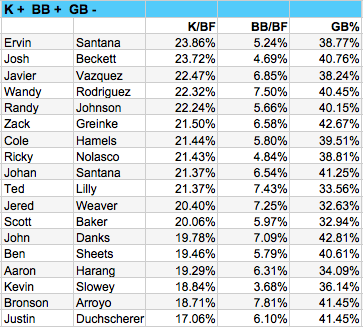

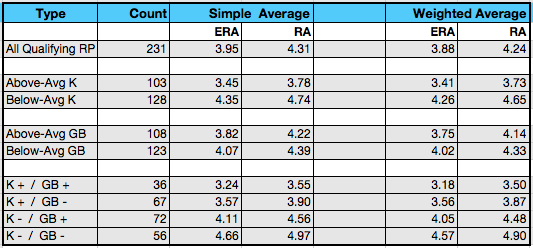

On average, we know that pitchers in the northeast quadrant and those with above-average K-BB-GB rates fared better than their peers, yet many of the top hurlers fell into the southeast quadrant despite sporting strikeout rates – the most important variable of the three – that were superior to many of their counterparts in the more tony neighborhood of the NEQ. So which one is better? A pitcher with above-average K and GB/K-BB-GB rates or one with an outstanding K rate and more modest BB-GB rates?

To help answer that question, Ryan posted a spreadsheet with z-scores on a fantasy baseball website that linked to one of my articles above. After reading the thread and a comment that he left on our site, I contacted him and proposed that he weight the three variables by their relative impact rather than evenly. The deltas in above-average and below-average ERA and R (vs. their means) for each of the various classifications as well as the individual K, BB, and GB correlations to ERA and RA suggested to me that strikeout rates were nearly two times as important as walk rates and five times as important as groundball rates. The best-fit ratio was approximately 5:3:1 or 5:2.5:1.

If you're one of the statheads, fantasy geeks, or baseball nerds still with me, here are the correlation coefficients for strikeout, walk, and groundball rates to ERA and RA for the universe of 135 starting pitchers with 100 or more innings last year:

K BB GB

ERA -0.5786 0.3306 -0.1121

RA -0.5918 0.3118 -0.0796

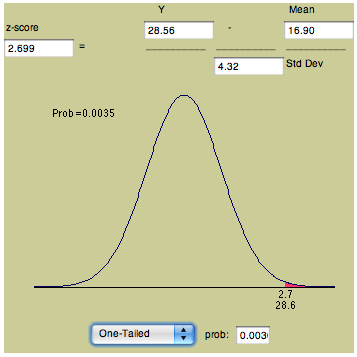

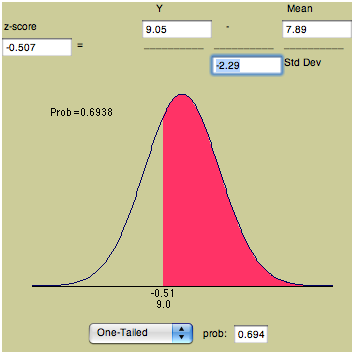

Using standard deviations (4.32% for K, 2.29% for BB, and 6.70% for GB), Ryan created z-scores (which indicate how many standard deviations an observation is above or below the mean) and then weighted them using the 5:2.5:1 ratios as mentioned above. The latter produced correlations of -0.7228 for ERA and -0.7203 for RA. By squaring these correlations, we produce coefficient of determinations (R²) that provide measures of how well outcomes are predicted by the model. Accordingly, the 5:2.5:1 weighting explains about 50 percent of a pitcher's ERA and RA, which is incredibly high given that team defense accounts for the lion's share of the unexplained balance. While we can improve the R² by substituting HR rates for GB, the former is not as reliable as the latter in terms of predicting future performance.

The K-BB-GB rates and z-score rankings can be accessed in this spreadsheet. The 135 qualifying pitchers were separated in quintiles by color. As such, there are 27 starters in each grouping or about one per team. If you'd like, think in terms of each quintile as No. 1s, No. 2s, No. 3s, No. 4s, and No. 5s in starting rotations. The reality is that front, middle, and back of the rotation starters are determined based on quality (which is the sole determinant of these rankings) and quantity (ability to pitch every fifth day, go deep into games, and amass a lot of innings over the course of a season).

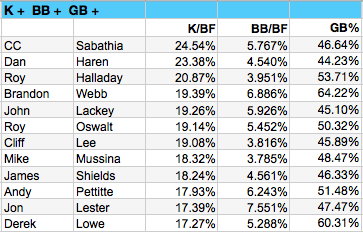

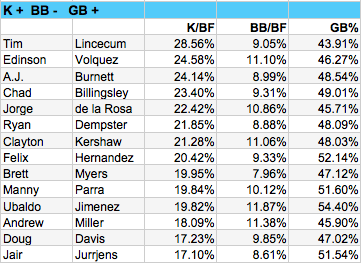

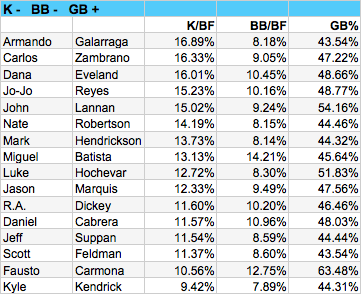

The top quintile is presented below.

Tim Lincecum, CC Sabathia, Dan Haren, Roy Halladay, A.J. Burnett, Cliff Lee, Brandon Webb, Mike Mussina, Chad Billingsley, Roy Oswalt, Edinson Volquez, Derek Lowe, James Shields, and Ryan Dempster are all residents of the northeast quadrant. Sabathia, Haren, Halladay, Lee, Webb, Mussina, Oswalt, Lowe, and Shields are nine of the dozen pitchers from the K+/BB+/GB+ grouping. The other three are John Lackey, who heads up the second quintile; Andy Pettitte, ranked fourth in the second quintile and 31st overall; and Jon Lester, another member of the second quintile.

For purposes of illustration, I have included Lincecum's z-scores for K/BF and BB/BF (top row) and GB (bottom row) below. The colored portion of the normal distribution represents the area of probability. (You can compute your own z-scores in this applet.)

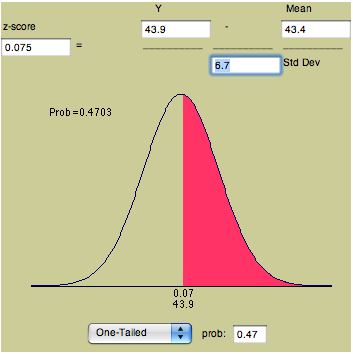

Lastly, here are the top 30 relievers as measured by z-scores.

Mariano Rivera and Jonathan Papelbon 1-2. There must be something to this methodology.

| Designated Hitter | February 19, 2009 |

Last week, we looked at how we can interpret groundball averages and what they tell us about the defensive overshift. Now, we'd like to examine some of the more interesting points in our dataset. Of all left-handed batters with at least 200 grounders since 2002, who had the most success with the worm-burner?

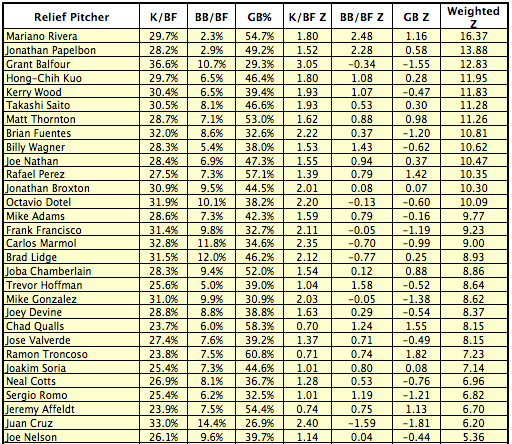

The chart is sorted by groundball average, which for lefties averages out around .225-.230. It is followed by expected groundball average based on pull-to-opposite-field-groundball ratio, speed score, percentage of groundballs to center field, homers per ball in air, and bunts per plate appearance.

Fred Lewis is quite the ballplayer. He has one of the top speed scores in our sample, and according to Pizza Cutter’s speed scores, he was one of the top 35 fastest players in the game last year. But he makes the most of his abilities. Not only can he leg out grounders, but by advanced metrics, he’s an above average left-fielder and baserunner. He stretches hits into triples and is willing to draw a walk to boot. Just wanted to make that observation before we get to...

Land of the Rising GBAVG

Ever notice that all four current Japanese Major League regular position players bat left handed? Though Ichiro Suzuki, Akinori Iwamura, Hideki Matsui, and Kosuke Fukudome all slugged at least 95 points higher in Japan than they have in America, there is one department in which they presumably haven’t suffered since coming overseas. All four players have a strong propensity to reach base via the groundball. Iwamura, Ichiro, and Fukudome all show up on the top 10 list, while Matsui checks in with a .246 groundball average, impressive considering his affliction going the other way. Calculating the difference between their groundball average, and their “expected” groundball average, all four come up in the 20 most “lucky” hitters. However, we wouldn’t attribute their success to luck at all. Ichiro is famous for his unique swing, in which he opens his bottom half and basically is halfway down the line by the time he makes contact. Could this be a method that is taught in Japan? If so, it would probably give someone a much better chance than other lefties of reaching base on grounders. Looking at cherry-picked at-bats, we can say that Iwamura, Matsui, and Fukudome all at times follow similar approaches.

We can estimate that without this skill, over the observed years, Iwamura would have a .260 batting average instead of .280, while Ichiro would be a .310 hitter instead of .330, Matsui .285 instead of .295 and Fukudome .245 instead of .255. This is a remarkable ability. It would be difficult to quantify, but perhaps teams can start timing how long it takes for a batter to get to first following contact. While Matsui has yet to bunt in his career, Ichiro, Iwamura, and Fukudome all get hits on over half their bunt attempts. Perhaps in Japan they emphasize getting down the line, and perhaps in America they should start looking into that. (Cough, Manny, Cough.)

The players we've looked at so far all make the most of their speed and groundball opportunities. But who doesn't? Without further ado...

The Willie Mays Hayes All-Stars

“You gotta stop swingin’ for the fences though, Hayes. All you’re gonna do is give yourself a hernia. With your speed you should be hittin’ the ball on the ground, leggin’ ‘em out. Every time I see you hit one in the air, you owe me twenty pushups.” --Lou Brown (Major League)

Disclaimer: It would be quite a rare instance to find a player who would actually benefit from hitting more grounders than flyballs. We suggest referencing The Hardball Times Baseball Annuals to find specific run values for players' different batted ball types. These are simply players who do a great job reaching base on grounders but fail to do so often.

Chone Figgins: From the right side, it’s acceptable that he doesn't hit many groundballs. Batting righty, he has hit only .230 on grounders over the last six years, while he is also more likely go earn a hit when he gets underneath the ball from that side of the plate than when he does so from the left side. Meanwhile, Figgins not only bats a robust .290 on grounders from his left side but is also very successful bunter. So when Figgins swings for the fences with his career .100 ISO from the left-handed box, know he might be better off legging out grounders.

Iwamura: Aki may have been a 30 homerun a year hitter in Japan, but not anymore, as he is twice as likely to have his groundballs go for hits than his fly balls. His homerun per flyball ratio has decreased to 3.7% this year, and the average true distance of his homeruns has gone down nearly ten feet as well, according to hit tracker. But he’s still a monster when he puts the ball into the turf, except he does so at only a league average rate.

Mark Bellhorn is the final player on this list, and oddly, another 2b/3b combo. Bellhorn may never get another cup of coffee, so it is likely too late for him to change his approach. But it warrants mentioning that he's always been underappreciated in his career due to his strong secondary skills, and he's been able to compile a nice groundball average despite a low groundball percentage.

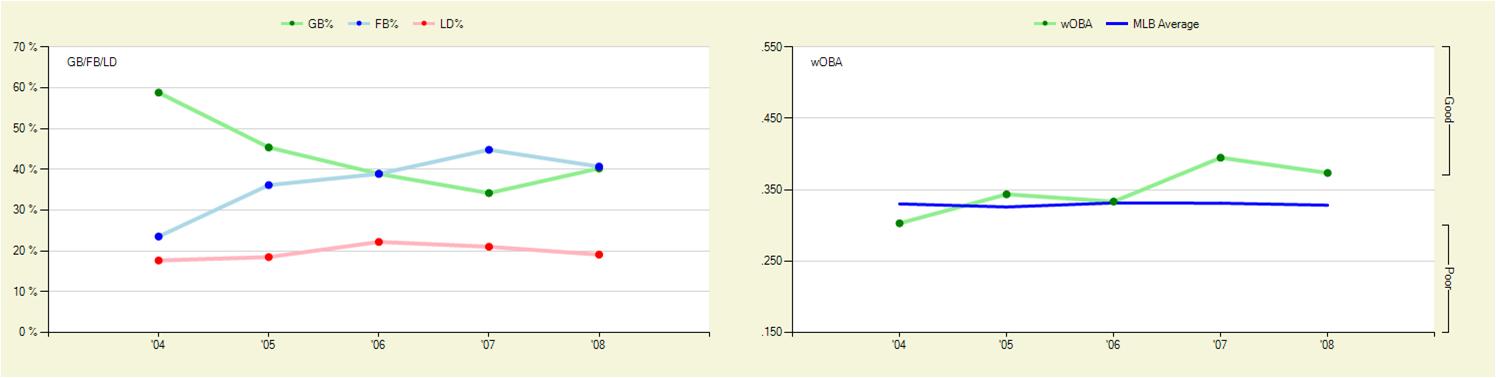

Curtis Granderson and Brian Roberts could also be on this list, except that they're able to hit however they please and remain successful. Both players hit balls in the air almost twice as often as on the ground, though they hold solid career GB averages in the .265-.275 range. But Roberts consistently hits for decent power, and while Granderson has been excellent at reaching base on ground balls all four full years of his Major League career, he has done a good job of decreasing his groundball percentage as his power has increased--perhaps a conscious decision. Take a look at these graphs:

Follow the green lines. As his groundball percentage decreases, his production as measured by wOBA has increased. Though he hit .305 on grounders this year, putting the ball on the ground actually hurt his overall line it appears. He's a better hitter when hitting fewer groundballs, or he hits fewer groundballs to be a better hitter. Either way, he's done a great job improving at the plate

Taking a quick look at righties who weren’t in our dataset: Over the last three years, the only player to have popped up 20% of his fly balls was Eric Byrnes, with a 25.2 infield flyball percentage. As one of the faster players in the game, he could probably use to hit a few more grounders, and he has hit .296 on them since 2002. Carlos Gomez has a similar batted ball profile to that of Byrnes, except without the same type of pop, so he'll either want to develop some muscle or stop racking up 140 strikeouts with a .360 SLG when he might be better off at times pounding the ball into the ground and beating out the throw.

On the reverse end, grounders have been death to Mark Sweeney, Casey Kotchman, and Russ Adams, to the tune of a sub-.200 average, yet they still hit more balls on the ground than in the air.

That's it for our findings on batted ball data. Big thanks to FanGraphs and BillJamesOnline for making this type of data available. And we'd also like to express our deepest gratitude to Rich Lederer for hosting our research.

Leanne Brotsky, David Estabrook, Jeremy Greenhouse, Kimberly Miner, and Steven Smith assisted in writing this article. We would also like to thank Evan Chiachiaro and Dan Rathman, and Anthony Doina who participated in Baseball Analysis at Tufts’ research committee. Any questions can be directed to TuftsBAT@gmail.com.

| Baseball Beat | February 17, 2009 |

I have added a new wrinkle to our series of categorizing pitchers by including walks as well as strikeout and groundball rates. The best pitchers miss bats (K), keep batted balls in the park (GB), and command and control the strike zone (BB).

By evaluating all three variables, we can focus on what a pitcher exercises the most authority over. While this study is not intended to quantify a pitcher's Defense Independent Pitching Statistics or Fielding Independent Pitching ERA, it borrows from these concepts for the primary purpose of categorizing pitchers by types (high K, low BB, high GB to low K, high BB, and low GB and the other six combinations of highs and lows).

Tangotiger has written an easy-to-understand primer on the subject of the Defensive Responsibility Spectrum, which discusses DIPS and introduces FIP. As we know, pitchers have the greatest influence over items such as K, BB, HBP, and HR (as well as balks, pickoffs and, to a lesser degree, wild pitches).

While I intend to use HBP in the future by combining them with BB, I did not include the former in this first attempt at categorizing K, BB, and GB types. I also chose to substitute GB% for HR rates two years ago when I began this series because the latter tends to fluctuate more based on ballpark factors (distances, altitude, and wind) and perhaps, to a certain extent, luck.

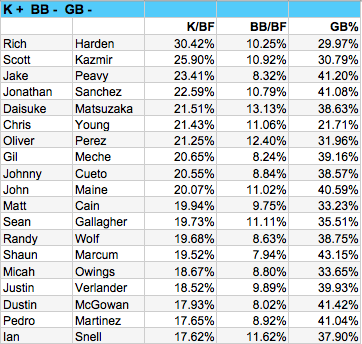

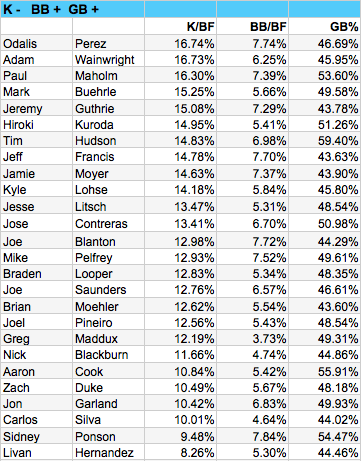

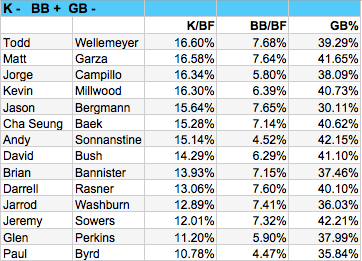

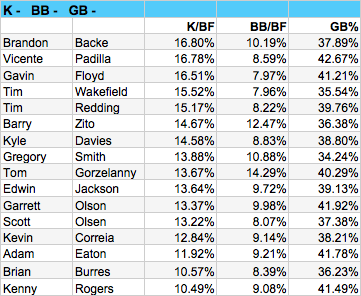

The results detailed in the table below are based on 135 pitchers who completed 100 or more innings and started in at least 33 percent of their appearances in 2008. Among these qualifiers, the average K/BF rate was 16.90%, the average GB rate was 43.45%, and the average BB/BF rate was 7.89%.

For ease of understanding and consistency, I have designated "better" than average with a plus sign ( + ) and "worse" than average with a minus sign ( - ). Based on these labels, one can readily see how different groups of pitchers fared last season.

As shown, strikeouts had the greatest impact on ERA and RA, followed by walks, and groundballs (which could also be thought of as batted balls as a more generic type). Accordingly, K+ BB+ GB+ > K+ BB+ GB- > K+ BB- GB+ > K+ BB- GB- > K- BB+ GB+ > K- BB+ GB- > K- BB- GB+ > K- BB- GB-.

As a rule of thumb, pitchers with plus strikeout rates will have a better-than-average ERA and RA. Conversely, pitchers with minus strikeout rates will have a worse-than-average ERA and RA. Both of these general principles apply irrespective of the other variables with one exception: pitchers with minus K rates combined with plus BB and GB rates will typically sport average ERA and RA.

Another key takeaway is that pitchers with plus K, BB, and GB rates as a group will produce ERA and RA that are about 1.00 better than average. At the other end of the spectrum, pitchers with minus K, BB, and GB rates as a group will fashion ERA and RA that are about 0.85 worse than average. Therefore, the difference between the best and worst groups is nearly two runs per nine innings. Disparities among the best and worst Individual pitchers will obviously be greater than these averages.

Let's take a look at these eight classifications of pitchers.

A valuable aspect of categorizing pitchers and listing K, BB, and GB rates is the ability to see comparable pitchers. Without applying similarity scores, one can see that John Lackey and Roy Oswalt are more alike than not with the latter producing slightly better walk and groundball rates. Both righthanders are fastball-slider-curveball types with Oswalt throwing a couple of miles-per-hour harder than Lackey. Oswalt gets the nod but probably not by as much as the differences in their career ERA+ (139 to 117).

Cliff Lee, Mike Mussina, and James Shields are bunched with the former getting the edge over the latter for his superior K and BB rates. Ervin Santana and Josh Beckett are hard-throwing (94.4 and 94.3 mph, respectively) righthanders with comparable K, BB, and GB rates. Dan Haren has a nearly identical K rate as Santana and Beckett but slightly better BB and GB rates. Although Javier Vazquez throws right and Wandy Rodriguez left, their fielding independent stats are not all that different even though the Houston starter is a relative unknown compared to the well-traveled, newly acquired Atlanta pitcher.

One of my favorite comps is Cole Hamels and Johan Santana, two of the best southpaws with plus-plus changeups. Ricky Nolasco may be just as good, or at least he was last year! The main difference between Jered Weaver and Scott Baker is that the latter has a roughly 20 percent better walk rate. Both righties are FB-SL-CH flyball types although Baker throws his heater about a mile per hour harder than Weaver.

A.J. Burnett and Chad Billingsley are two peas in a pod with respect to K, BB, and GB rates. Both throw gas and a hammer curve with A.J. lighting up the radar guns and his investment portfolio a bit more than his younger counterpart. When it comes to Felix Hernandez and Ubaldo Jimenez, there are more similarities (including the two hardest average fastballs in 2008) than differences as I first pointed out last July.

Other comps include Gil Meche and Johnny Cueto, Jesse Litsch and Braden Looper, Matt Garza and Gavin Floyd (and Todd Wellemeyer, Armando Galarraga, and Vicente Padilla, for that matter), and three back-to-back southpaw pairings: Dana Eveland and Jo-Jo Reyes (sporting similar FB-SL-CH repertoires), Nate Robertson and Mark Hendrickson, and, best of all, Jeff Francis and Jamie Moyer, two soft-tossing lefties with only 18 years separating them.

I will have a follow-up piece on Friday with a methodology to rank pitchers across all classifications.

| Baseball Beat | February 16, 2009 |

With pitchers and catchers reporting to camp (and a third of the position players as of Monday), the Major League Baseball season can't be too far away. Seven weeks to be exact. About the same time between now and then as it was between now and Christmas. It's just a matter of whether you like to open your presents in late December or early April.

The first spring training games will take place on Wednesday, February 25. With the Dodgers relocating to Arizona, there are now 16 teams in the Grapefruit League and 14 in the Cactus League. The American League clubs are split evenly between Florida and Arizona while the National League has nine of its 16 franchises training on the east coast.

Round one of the World Baseball Classic opens in Tokyo on Thursday, March 5. There are four pools consisting of four teams each for a total of 16 participants. Pool A consists of China, Chinese Taipei, Japan, and Korea. Pool B is comprised of Australia, Cuba, Mexico (host), and South Africa. Pool C is made up of Canada (host), Italy, USA, and Venezuela. Pool D includes Dominican Republic, Netherlands, Panama, and Puerto Rico (host). The winners and runners-up will advance to round two with the survivors from Pool A and B squaring off at Petco Park and Pool C and D meeting up at Dolphin Stadium. The semi-finals and finals will take place on March 21-23 at Dodger Stadium. The tournament will be televised by MLB Network (16 games) and ESPN (23 games). The full schedule (with dates, times, and TV network) can be viewed here. (Note: Several players listed on the rosters have opted not to play.)

In the meantime, Baseball America is counting down to the college baseball season. (Hint: It takes place this week.) Aaron Fitt, the site's lead college writer, provides scouting reports on the top 25 teams in the country (complete with projected lineups and 2008 stats).

I'm looking forward to attending the opening series between Long Beach State and USC next weekend. The Trojans will play host on Friday and Sunday while the Dirtbags will host the Saturday game. USC (ranked 24th by Collegiate Baseball) features Grant Green, a preseason first team All-America shortstop who is projected to be a top five overall pick in the MLB draft in June.

Green impressed me when I saw him (and fellow freshman Robert Stock, whose status has slipped since being named Baseball America's Youth Player of the Year in 2005) make his collegiate debut two years ago:

Green, Stock's freshman teammate, reminds me of Tulowitzki, the former Dirtbag who played 25 games for the Colorado Rockies in September. The 6-3, 180-pound shortstop has added about 15 pounds of muscle since being drafted by the San Diego Padres in the 14th round last June. He runs well, as evidenced by his 4.23 speed to first, a time that scouts would rate as a 55 or 60 for a RHB on their 20-80 scale.

After losing 11 players to the draft last year, Long Beach State is in the midst of a rebuilding campaign. Devin Lohman, who was selected in the 42nd round by the Rockies in 2007, will follow Danny Espinosa (WAS, 3rd round, 2008), Troy Tulowitzki, Bobby Crosby, and Chris Gomez (as well as a stint by Evan Longoria during his sophomore season in 2005 when Tulo missed 18 games with a hand injury), as the school's next shortstop. The sophomore hit a home run at cavernous Blair Field and made a couple of defensive gems in an intra-squad scrimmage on Saturday.

I am also hopeful of catching righthander Stephen Strasburg, the No. 1 prospect in the country, at the MLB Urban Invitational in Compton next weekend. San Diego State is scheduled to play Bethune Cookman on Friday and Southern on Saturday. If Strasburg is going, I will be, too.

If you don't know much about Strasburg, the following excerpt from a Baseball America article will whet your appetite:

The Washington Nationals have the first pick in the 2009 draft. Strasburg, a junior righthander at San Diego State, is the odds-on favorite for the first choice. So just how does a pitcher go from obscurity to the top of the draft?• By hitting 101 mph on a radar gun.

• By outdueling the first pitcher selected in last year's draft.

• By striking out 23 batters in a game.

• By being the first collegiate player selected to the U.S. Olympic team since professionals were put on the roster in 2000.

Strasburg did all that and more last year, making him The Next Big Thing. Everyone, it seems, is now on board.

College baseball this week. Spring training next week. World Baseball Classic next month. Opening Day the following month.

Bring 'em all on. I'm ready.

Meanwhile, if you're looking for some reading material, be aware that The Hardball Times Season Preview 2009 is now shipping. The book includes projections and commentaries for all 30 teams and over 1,000 players, draft strategies and values, and key rookies for 2009. You can read the first page of an eight-page preview of the Dodgers that I wrote. The other 29 teams are covered by THT's staff writers and many of the best baseball bloggers on the Internet.

| Around the Majors | February 13, 2009 |

As we saw last week in part one of Seasons of Change, MLB rosters can really evolve in 10 seasons. As fans, it's also fun to look back and remember some of the key moments - and players - that made 1999 so entertaining.

The Atlanta Braves | 103-59 (First)

The Braves club was a powerhouse 10 years ago, led by some excellent pitching, which included The Big Three of Tom Glavine, John Smoltz and Greg Maddux. Those three pitchers, combined, earned more than $25 million. The club also relied on two young, promising starters named Kevin Millwood, 24, and Odalis Perez, 22. Millwood went on to have a pretty decent career (until he hit Texas), while Perez never did realize his full potential. Millwood was actually second on the team in wins in 1999 with 18 (Maddux had 19) and led with 205 strikeouts. Chipper Jones led the club with 45 home runs and his 110 RBI total was second to Brian Jordan's 115. Chipper received all but three first-place votes to win the NL MVP. Has any (active) player in the last 10 years fallen further than Andruw Jones talent-wise? He hit .275/.365/.483 with 26 home runs at the age of 22 - and his offense was not even the best part of his game.

The New York Mets | 97-66 (Second)

Catcher Mike Piazza was the top salary earner for the Mets in 1999 at $7.1 million but he earned his paycheck by slugging 40 home runs and driving in 124 runs. Robin Ventura had his best season as a Met and hit 32 home runs with 120 RBI. He hit .301 in 1999 and never reached .250 again in his final five seasons. The third highest paid player on the club at $5.9 million was Bobby Bonilla, but he hit just .160/.277/.303 in 119 at-bats (60 games). The Mets' starting rotation was fairly old, with the top four pitchers aged 33 or higher, with No. 1 starter Orel Hershiser at 40. It's hard to believe the Mets won 97 games considering the top win total was 13 by both Hershiser and Al Leiter. The closer's role was shared by the Young n' Old combo of Armando Benitez, 26, (22 saves) and John Franco, 38, (19 saves).

The Florida Marlins | 64-98 (Fifth)

This club is famous for taking one step forward and two steps back. After winning the World Series in 1997, the club jettisoned most of its talent. In 1999, only four players made more than $1 million, including Alex Fernandez who raked in $7 million and earned seven wins in 24 starts. Fernandez earn more money than the next 13 highest paid players on the roster. The team lead in wins was secured by Brian Meadows with 11 (He also lost 15 and had an ERA of 5.60). Antonio Alfonseca led the club with 21 saves. Rookies A.J. Burnett and Vladimir Nunez appeared to have bright futures, while sophomore Ryan Dempster was also being counted on for big things. Offensively, not one hitter was above the age of 30 when the season began. Luis Castillo played his first full season as a regular and stole 50 bases. Preston Wilson, 24, hit 26 home runs and finished second in the Rookie of the Year voting. He also struck out 156 times, though. Mike Lowell also showed promise in his rookie season.

The Philadelphia Phillies | 77-85 (Third)

Paul Byrd and Curt Schilling led the Phillies in wins in 1999 with 15 a piece. Schilling was also tops with 152 strikeouts. Left-handed prospect Randy Wolf made his debut and posted a 5.55 era in 21 starts. Wayne Gomes led the club with 19 saves after veteran Jeff Brantley went down due to injury and appeared in just 10 games. The offense was led by catcher Mike Lieberthal, who hit 31 home runs and batted .300. Rico Brogna was first on the club in RBI with 102. Bobby Abreu, 25, had a breakout season that saw him hit 20 home runs, 11 triples, score 118 runs, steal 28 bases and walk 109 times. Oh, and he batted .335. Doug Glanville had 204 hits and also stole 34 bases.

The Montreal Expos | 68-94 (Fourth)