| Baseball Beat | December 31, 2007 |

"Missed it by THAT much" was made famous by Don Adams in his role as the clueless secret agent Maxwell Smart in the 1960s comedy series "Get Smart." Smart, also known as Agent 86, would utter his catch phrase while holding up his thumb and forefinger to demonstrate how close he was to pulling off a heroic super spy move.

Well, there have been numerous baseball players whose careers "missed it by that much" when it came time to vote for their worthiness as Hall of Famers. Gil Hodges, the only player to earn 50% or more of the vote and never get elected, is the poster boy for this dubious distinction.

I've always found it interesting how some candidates for the Hall of Fame get dismissed summarily while others get a second look (or more). Will Clark, Darrell Evans, Bobby Grich, Ted Simmons, Lou Whitaker, Dan Quisenberry, Bret Saberhagen, and Dave Stieb were all "one and done" guys. All eight of these players were as good or better than one or more Hall of Famers at their positions, yet not a single one received as much as 5% of the vote in their lone shot at baseball immortality. Smart would have simply said, "Sorry about that."

Granted, the Hall of Fame vote is a binary choice: it's either a "yes" or a "no." There's no place on the ballot for "maybe" or "gosh, he was awfully good...shouldn't we honor him in some other way?"

That said, in practice, many writers will not vote for a player in his first year of eligibility because they do not believe he is worthy of being a "first-ballot Hall of Famer." It's not only a silly distinction – either you're good enough in year one or you're not – but this type of thinking runs the risk that a fully qualified candidate could get booted if enough voters acted in this manner. It's unlikely, but it's certainly possible.

"Now Listen Carefully"

One way around this dilemma would be to add a category, as has been proposed by Tom Tango, that would enable writers to check the following box: "I need more time to think about this candidate." To be honest, I've never been too fond of this idea because a voter shouldn't need more than five years to think about a player's Hall of Fame worthiness. However, the time may have come to adopt something like this, especially in view of the fact that many star players from the so-called "steroid era" have now retired or will be calling it quits in the not too distant future.

Now, one can argue "for" or "against" players from this era all you want. But the whole issue might be a bit more complicated than just saying so and so cheated or that it doesn't matter. As for me, I would hope writers would either vote "yes" or "no" based on the player's merits or admit they need more time to sort this matter out.

The Hall of the Very Good has made its way into the baseball lexicon in recent years. I think most of us would agree that players like Norm Cash, Orel Hershiser, Fred Lynn, Rick Reuschel, Reggie Smith, and Jimmy Wynn all came up a little short in meeting the standards for the Hall of Fame. (Notice that I didn't mention Ron Santo as I'm still holding out hope for him.)

With respect to the Hall of the Very Good, I would like to submit a first-year eligible pitcher from this year's ballot for inclusion. He won't come close to sniffing the required 5% in order to keep his name on next year's ballot. His name? Chuck Finley.

Let me be perfectly clear here. I do not believe Chuck Finley is a Hall of Famer. However, I believe he was a better pitcher than generally recognized.

There are dozens of players who are deserving of the mythical HOTVG, yet are rarely even thought of in those terms. I would submit that Finley is one of those players. How many baseball fans realize that the tall lefthander from Monroe, Louisiana won 200 games during his career? Or that he had seven seasons in which he won 15 or more contests? Or that Chuck ranks 22nd in career strikeouts among all pitchers since 1900? Or that he had back-to-back years with ERAs under 2.60?

How many sabermetricians realize that Finley is tied for 62nd in Runs Saved Against Average in the modern era? Or that his ERA+ is 115? He's eighth in ERA+ among pitchers eligible for the HOF with 3,000 or more innings.

The bottom line is that Finley pitched at a high level for a long time. In fact, higher and longer than most fans realize.

Hold on, while I answer my shoe phone . . . I think it's Billy Pierce on the other end.

Jerry Crasnick of ESPN wrote an article a few days ago on (Chuck) Tanner backing Gossage, Blyleven. Crasnick, whose "License To Deal" is one of the best books on the world of agents, called me last Wednesday and we spoke for about 20 minutes.

But Blyleven's supporters swear by his Hall-worthiness. Rich Lederer, a baseball analyst and historian, studied Blyleven's career and estimates that if he had received even league-average run support, his record would be closer to 313-224 than his 287-250."I don't think people have taken the time to look at the statistics closely enough to appreciate how dominant he was," Lederer said. "If he had won 13 more games, I don't think we'd even be having this discussion right now."

I should point out that the win-loss records with "league-average run support" are courtesy of Lee Sinins and his Complete Baseball Encyclopedia.

The Hall of Fame ballots must be postmarked no later than today. The results of the voting will be announced on Tuesday, January 8.

Update (01/01/08): According to Keith Law, Blyleven has been named on 68% (58 of 85) of the ballots he has seen. Polling at 89%, Gossage appears to be a lock this year. If Blyleven can finish with the most votes among those who do not get elected, he will be like the Goose this year and become the favorite to get the additional support next time around.

[Additional reader comments and retorts at the Baseball Think Factory/Baseball Primer Newsblog with a focus on the merits of ERA+.]

| Weekend Blog | December 29, 2007 |

While there has been much discussion on these here intertubes about the BBWAA and who should and should not be admitted, the Hall of Fame is in no way affiliated with the organization other than, well, they always have been. The institution seems satisfied with its electorate, however. A smattering of direct quotes from a number of its voters who have publicly displayed their ballots follows.

==========

I visualized aging Dodger Tommy John and his surgically repaired left elbow - the tendon graft now bears his name and is as common as a tonsillectomy - totally dominating the Phillies in Game 4 of the 1977 LCS. That was a night when Steve Carlton slipped, slid and failed on a rain-swept mound that John handled as if he were in Dodger Stadium on a hot Sunday afternoon. Suddenly, Tommy John and his 288 wins during a long, injury-interrupted career looked Cooperstownish. He won't get in; this is his 14th year on the ballot, but he has both my vote and appreciation for what he meant to a dying era of pitching and pitcher.

- Bill Conlin, The Philadelphia Daily News, depending on his personal recollection of Tommy John's footing one evening on a Veterans Stadium mound in throwing his support behind the southpaw.

==========

Jim Rice, the most feared hitter of his time in the American League...

- Bill Kennedy, The Times of Trenton, evidencing the most tired of claims. Rice was so feared, that Managers intentionally walked him less than 48 other players between 1974 and 1989, the span of Rice's career.

==========

The best new names on this year's ballot are Tim Raines and David Justice. Rice beats both.

- Dan Shaughnessy, The Boston Globe, commenting on Rice "beating" Tim Raines. Raines's career WARP3 number, an imperfect figure that does a quick and dirty job of measuring output adjusted for playing environment, bests Rice's by over 40 wins.

Managers thought about intentionally walking him when he came to the plate with the bases loaded.

- Shaughnessy on Rice in the

==========

Going primarily on what I saw, rather than mere numbers, I cast my annual votes for the best reliever of the era, Goose Gossage; the best starting pitcher, Jack Morris; and the best outfielder, Andre Dawson.

- Jim Alexander, The Press Enterprise. Of relievers who appeared in at least 400 games during Gossage's career span, Goose ranks 20th in ERA+. Of starters who started 400 games or more from 1977 to 1994, Morris ranks 8th in ERA+ out of 20 qualifiers. Of outfielders who had 7,000 plate appearances or more between 1976 and 1996, Dawson ranks 15th in OPS+ out of 21 qualifiers.

==========

Enshrinement in Cooperstown shouldn't be about numbers. If anyone thinks so, let's trash tradition and have a computer select the honorees.

The Hall of Fame should be about who starred and who dominated. And about who made an impact.

- Jon Heyman, Sports Illustrated, before proceeding to cite number after number in evidencing his choices for the Hall.

The ace of three World Series teams, it's an abomination he may never get in.

- Heyman (from the same piece) emphatically supporting Jack Morris, while choosing to pass over Blyleven. In case you missed it, Morris has already been devastatingly discredited vis-a-vis Blyleven by our very own Rich Lederer.

The reason I am in that 10 percent is that I think he was perhaps the best all-around shortstop of his generation and an underrated piece of the Big Red Machine.

- Heyman, who is not voting for Alan Trammell, on Dave Concepcion. There are no words.

He was an MVP, an All-Star Game MVP, a two-time batting champion, a seven-time All-Star and a three-time Gold Glove winner.

- Heyman, who is not voting for Tim Raines, on Dave Parker. Again, speechless.

==========

Sorry, Yankees fans, but when you break it down, there were four brilliant years (1984-87), two very good ones (1988-89) and two decent ones (1992-93), and not much else. No.

- Ken Davidoff of Newsday commenting without any sense for irony on Don Mattingly while touting Rice's candidacy in the same piece.

==========

Rich ''Goose'' Gossage: The very definition of ''lights out'' closer, this intimidator is the equal of already enshrined firemen Bruce Sutter and Rollie Fingers.

- Don Bostom of The Morning Call on the candidacy rationale for Goose Gossage, who ranks 39th all time among relievers who have appeared in at least 400 games with a 126 ERA+. Amongst the same group, the "very definition of 'lights out' ranks 74th with a 7.47 K/9.

==========

The biggest debates for me were Tim Raines, who obviously was overshadowed by Rickey Henderson, but also if you take Vince Coleman's five top years, I would say he outperformed Raines, too, and I don't see Coleman as a Hall of Famer.

- Tracy Ringolsby, The Rocky Mountain News

==========

For those interested, I would vote for Gossage (his sustained excellence warrants it despite my comments above), Raines, Blyleven and Trammell. I make the points above to highlight that more is needed than throwaway lines, conjecture and memory to credit/discredit any one player's candidacy.

- Patrick Sullivan, 12/29/2007, 12:05 EST

=====================

With a hat tip to Baseball Think Factory for directing me there, the peerless Joe Posnanski chimes in with this stream of consciousness Blyleven-Morris comparison.

Hmm, so you’re telling me that Blyleven has 33 more wins, 32 more shutouts, 1,223 more strikeouts, 68 fewer walks, an ERA that more than a half run better, an ERA+ that’s 13 points better, a better overall postseason record and five or six individual seasons that were better than Jack Morris’ best season … wow, can I have a few more minutes to think about this? Wait, Blyleven had a lot more losses too, so that, oh, he played for worse teams, yeah, that might have had something do with that, um, hold on, I need to sharpen my No. 2 pencil and think about this …

He goes on to explain his main problem with certain individuals in the Morris camp.

No, I hate the campaign for the same reason that comedian Gary Gulman hates Pepperidge Farm cookies. “They’re a good cookie, but they’re so full of themselves with their names, they’re so bombastic, they’re like, ‘Oh, this is the Milano, and this is the Bordeaux, and the Geneva, and the Brussels cookie, and I’m like, ‘Wow, what a world traveler, where did I run into you again? Oh, that’s right. Target.’”That’s how I feel about a few (not all) of the Morris Hall of Fame people. Just be humble. Don’t get in my face with your, “Jack Morris was the greatest pitcher of his era,” garbage. Hey, if you want to say, “Look, here’s a guy who had some longevity, he threw a lot of innings every year, he pitched one fabulous postseason game, and, hey, he did win 254 games in his career,” I could see the argument. I probably wouldn’t vote for him, no but I could see the argument.

Wrong, Joe. Morris's exclusion would be an abomination. Jon Heyman told me so.

- Patrick Sullivan, 12/29/2007, 11:41 AM EST

===================

We have another Hall of Fame ballot posted publicly, this one from Gerry Fraley of The Sporting News. There were a few problematic items on his ballot but as these things go, his rationale was somewhat sound.

Except for this. What follows is Fraley's reasoning for leaving Tim Raines off of his ballot.

Raines' case was hurt by his reluctance to run in all situations, as Rickey Henderson did. Raines seemed at times too concerned about preserving his stolen-base percentage.

- Patrick Sullivan, 12/29/2007, 12:09 PM EST

| Baseball Beat | December 28, 2007 |

As a follow-up to 30 Rock, I thought it would be interesting to read what Bill James had to say about Tim Raines in the 1982-1988 Baseball Abstracts. The Abstracts hit the bookstores in the spring and were based on the previous season (e.g., the 1982 Baseball Abstract covered the 1981 campaign). As such, a look back at the Ballantine-published Baseball Abstracts gives us a glimpse of what James thought about Raines in real time during Tim's first seven seasons in the bigs.

I believe you will find the following commentary of interest with respect to both James and Raines.

1982

James ranked Raines third in his list of left fielders in the 1982 Baseball Abstract, behind Rickey Henderson and George Foster. In the "Introduction of the Player Ratings and Comments," James wrote: "This year's player evaluations, unlike the ratings I have presented in the past, are based solely on the player's performance during the 1981 season."

According to James, a player's offensive won-lost percentage is:

The offensive won-lost method is adjusted for what James termed "park illusions." "If a player plays in a park which increases offensive production by 10%, his runs created are divided by 1.05 before his OWL percentage is figured." In the team section, James concluded that "Olympic Stadium reduces offensive production by approximately 4%."

If one wanted to convert the W-L % into a W-L record, you would divide the player's outs by 25 (which is the approximate number of outs per game rounded down) to get an equivalent number of games. The number of games multiplied by the player's W-L % equals the number of offensive wins. Games minus wins results in the number of losses.

With respect to defensive won-lost percentage, James opted to use two decimals. "To use three decimals here would imply a degree of accuracy which is entirely non-existent." You gotta love his candor.

3. Tim RAINES, Montreal (.691)Offensive: .783

Defensive: .50

Playing Time: 90%Home-road breakdowns (.347 and .265) shouldn't be taken too seriously on 150 at bats each place. Raines has already established 21% chance of breaking Brock's career stolen base record. I'm anxious to get the season started and see how many he can steal. His offensive won-lost percentage is the best in baseball for a left fielder, but his defensive stats were so-so; I suppose you know he never played the outfield in the minors.

1983

Switching to a rating system based on the previous two years, James ranked Raines fourth among all left fielders in the 1983 Baseball Abstract.

4. Tim RAINES, Montreal (21-12)By the lead-off formula given in the Henderson comment, Raines ranks as by far the best lead-off man in the National League. But the formula says he should have scored 111 runs, and he wasn't anywhere near that (he had 90; the -21 is easily the largest discrepancy of the season). This suggests two things: 1) that the Expos lacked a decent #2 hitter, which it is pretty obvious they did, and 2) that all of the Montreal fans who wrote to me that Dawson wasn't hitting anything in the clutch probably weren't imagining it.

TRIVIA TIME – He came to the majors as an infielder, he was shifted to left field as a rookie, he had an outstanding rookie year in which he led the National League in stolen bases, he was then shifted back to second base, and he had a long and outstanding career in the major leagues as a second baseman. Who is he?

I'm not going to give you the answer, by the way. But I'll give you a hint: he is still active and at the major-league level in some phase of the game. (19-10; 3-2)

The latter two figures are offensive and defensive won-lost records.

1984

In "How The Ratings Are Derived" in the 1984 Baseball Abstract, James stated that "the parenthetical expression at the beginning of the player comment gives the combined number of wins and losses that the player has produced for his team over the last two years."

1. Tim RAINES, Montreal (28-15)Missed becoming the first man to score 20% of his team's runs by only three runs scored. The record for scoring the largest share of your team's runs is held by Kindly Old Burt Shotton of the 1913 St. Louis Browns (I don't think he was "Kindly Old" at the time) who has to be one of the few St. Louis Browns to hold a single season mark of any kind. George Sisler's hit record of 1920 is the only other one to come to mind.

Raines did establish a new NL record, breaking the old one set by Mays in 1964 by a good margin.

Raines and Henderson are two of the few leadoff men on this list; Shotton was another. Mostly, they're sluggers.

An interesting thing is that most of the players come from relatively good teams; there don't seem to be too many cases of exploitation of a team's low production. Shotton is the only member of a last-place team on the list, although Chapman's, Davis' and Billy Williams' teams were under .500. – Jim Baker

In the Henderson comments, James wrote, "The ratings are mixed up here; Rickey should be #1, Raines #2 and Rice #3. This happens because of a small flaw in the rating system, having to do with rounding the won/lost records into integers. Henderson is listed at 26 wins, 14 losses, but his two-year winning percentage is actually .659, not .650. I'll try to get that problem straightened out by next year."

1985

In the 1985 Baseball Abstract, James broke down the rankings by league. Raines was listed as a center fielder.

2. Tim RAINES, MontrealStrengths: Hitting for average, speed, range, line-drive power, strike zone judgment.

Weaknesses: See below.The 1984 Montreal Expos, not meaning to slight Charlie Lee (sic) or anything, had essentially two strengths. In Gary Carter, they had one of the greatest catchers in the history of baseball. In Tim Raines, they had the outstanding lead-off man in the history of the National League. Raines hit .309, got on base almost 40% of the time, reached scoring position under his own power 130 times (with the help of 75 stolen bases and 38 doubles) and, playing center field, was second among National League outfielders in putouts. Raines scored 106 runs with a terrible offense coming up behind him, led the league in stolen bases and is now five years ahead of Lou Brock's pace as a base stealer. He doesn't throw real great, but if you've got to have a weakness that's a good one to choose, because it really doesn't cost the team a half-dozen runs a year. He is a great ballplayer, one of the ten best in baseball.

So what do they do? Of course: They trade off the catcher and worry about the center fielder's throwing arm. It's crazy, but if you're losing and you're frustrated, it seems logical. Losing ball teams focus their frustration on their best players in exactly the same way that a man who gets fired from his job and loses his house to the bank will then divorce his wife, who is the only thing in his life that's worth hanging onto. You know how the story goes from there. If Andre Dawson doesn't come back and play the way he did before his knees went, the Expos will lose ninety games this year.

1986

James continued to rate players within their league in the 1986 Baseball Abstract. However, the players were rated by "a poll of the scorers who participated in Project Scoresheet." James claimed there were two reasons for allowing these scorers to vote. "One was to reward, and thus encourage, participation in the project. The other is that I sincerely believe that it's the best way that I can devise to rate the players."

The parenthetical numbers next to the names represent the number of precincts in which the player finished first in the voting. The voters from Project Scoresheet ranked Raines second among left fielders.

2. Tim RAINES, Montreal (1)Now clearly the greatest lead-off man in National League history. He hit .326 on artificial turf, the highest turf average of any player who played on turf in his home park. His .788 offensive winning percentage was third in the league, behind Guerrero and Strawberry. As mentioned in the San Diego comment, Montreal lead-off men – Raines, for the most part – scored 128 runs, by far the largest percentage of team runs scored by any batting position in the league. A great, great player.

1987

The players were once again rated in the 1987 Baseball Abstract by a poll of approximately 140 scorers participating in Project Scoresheet. The voters were divided into 26 precincts, one representing each major-league team. "The voters were asked to rank the players on the basis of present, clearly established ability."

Raines was ranked number one among all NL left fielders and given 1 1/2 pages of space. It may be a bit long, but it is well worth your time and, in my opinion, should be required reading for all HOF voters. Give yourself three units of credit in Sabermetrics 101 for tackling the following:

1. Tim Raines, Montreal (11)He would have been a deserving recipient of the National League Most Valuable Player award last year, which is not to say that Schmidt wasn't.

If you compare them offensively, Schmidt and Raines are oddly similar in dissimilar ways. They went to the plate almost the same number of times, 664 for Raines and 657 for Schmidt. Offense in baseball consists of two things: getting runners on base, and advancing runners. Raines won the batting title, and with seventy walks also led the National League in on-base percentage, at .413. Schmidt hit .290 himself and drew 89 walks besides, so that he was on base a lot, too. With adjustments for getting caught stealing and grounding into double plays (we penalize the hitter for taking other runners off base), Raines is credited by the runs created formula with being on base 259 times to Schmidt's 246. Close, but the edge to Raines.

As to advancing runners, Schmidt because of his power, had 302 total bases, which is the largest factor in the advancement of runners. However, Raines had 54 extra base hits himself (35-10-9), and being the batting champion, he too had 276 total bases. In addition, Raines stole 70 bases, 69 more than Schmidt. Although the runs created method considers the value of this to be equivalent to only 36 batting bases, with an adjustment for stolen bases and miscellaneous stuff, Schmidt is credited with 326 "advancement bases" by the runs created method, while Raines is credited with 333. Again, it's very close, but again Raines has the edge. Raines did slightly more to advance himself or other baserunners than did Schmidt.

Putting the elements together, you get:

Schmidt Raines On Base 246 259 Advancement Bases 326 333 Plate appearances 657 664 Runs Created 122 130They're very similar, oddly similar in the proportions, but Raines probably created about eight more runs for his team than did Schmidt.

Then you have to put that into a context of outs. Schmidt made 392 batting outs (552 minus 160) and 19 miscellaneous outs (9 sacrifices, 2 caught stealing, and 8 double plays). Raines made 386 batting outs (580 minus 194) and also made 19 miscellaneous outs (4 sacrifices, 9 caught stealing, and 6 double plays). The totals are 411 outs for Schmidt, 405 for Raines.

Putting the runs in a 27-out context, you have 8.01 runs created per 27 outs for Schmidt, and 8.66 for Raines. They are one-two in the league, but Raines's small advantages add up to a significant edge, making him pretty clearly the best offensive player in the league.

Except, of course, that Schmidt drove in and scored more runs than did Raines. I'll finish the MVP argument for Raines, and then I'll get back to that.

1) Raines created more runs than Schmidt despite playing in a much tougher hitter's park. Raines's batting and slugging percentages were 16 and 50 points higher on the road than they were in Montreal. Schmidt's batting and slugging averages were 16 and 94 points higher in Philadelphia than on the road. With adjustments for the statistical distortions of the parks, Raines was really a much better hitter. Further, the average Phillies game had 9.0 runs, whereas the average Expos game had only 8.2 runs, so the runs that Raines created were more valuable – had more of a win impact – than the runs that Schmidt created in his inflated environment.

2) Schmidt at 36 started the season at first base, and spent most of the season at third base, where he was an ordinary defensive player at a somewhat key defensive position. Raines played left field, where he is an exceptional defensive player at what is not a key defensive position. Raines was third in the league in outfield assists, and twice ended games by throwing out the potential tying run at the plate. We can call their defense a wash.

3) Neither player's team was ultimately successful, but Raines's early season streak of reaching base in 42 straight games helped greatly to keep the Expos in the pennant race. It wasn't ultimately meaningful, but it was very meaningful at the time. Schmidt piled up 67 RBI over the last three months of the season, when the Phillies were already dead and buried as a team. Not wanting to seem too eager to claim advantages for Raines, we'll call that a wash, too.

4) Schmidt has been a great player, but he has won the award twice before. Raines has been a great player for six years now, and he's never won it. In the interests of fairness, 1986 would have been an opportunity to balance the scales.

OK, then we go back to the issue of actual run and RBI counts. I would say this: that if Schmidt's advantage in runs scored and RBI resulted from his superior performance in run-production situations, then it is reasonable to consider this an advantage for Schmidt. If, on the other hand, the advantage resulted from offensive context (that is, having better hitters surrounding him), then it is unfair to penalize Raines because his teammates were not as good as Schmidt's.

Quite clearly, those differences resulted primarily from offensive context, and not from inidividual differences. Consider:

1) Schmidt drove in 25% of the runners that he inherited in scoring position. Raines drove in 26%. The big difference in RBI was that Schmidt came to the plate with 253 runners in scoring position, and Raines came up with only 173 ducks on the pond.

2) Schmidt drove in 49% of his runners on third base with less than two out, 20 of 41. Raines drove in 58% of his, 18 of 31.

3) Another situation in which at bats have a disproportionate impact on runs resulting is the first at bat in the inning, the leadoff spot. Raines had 190 such at bats, and Schmidt 142. In that game situation, power increases for most hitters but on-base percentage decreases, as pitchers concentrate on not allowing walks.

Schmidt's slugging percentage increased only nine points in that situation, from .547 to .556, while his on base percentage plummeted (all of this data is in the Great American Baseball Stat Book) from .390 to .340, 50 points. Adding the two together, he lost 41 points (+9, -50). Raines, on the other hand, increased his slugging percentage as a leadoff hitter by 35 points, to .511, while his on-base percentage dropped only to .404, 9 points, so he showed net gain of +26 (+35, -9). A big edge to Raines.

In the late innings of close games, pitchers strive to avoid the game-breaking homer, so exactly the opposite happens: Slugging percentages go down, while on-base percentages go up. Both players hit almost their averages in the late innings of close games – Schmidt .290 (+ or - zero) and Raines .339 (up 6 points). But again, Schmidt's slugging percentage went down 31 points while his on-base percentage went up only 21, a net loss of 10 points. Raines's slugging went down 24, but his on-base percentage went up 28, a net gain of four points. So again, Raines exploited the positives of a critical game situation more effectively than did Schmidt.

So it seems obvious that Schmidt's higher run counts resulted not from his own ability, but from the fact that he was hitting in the middle of Gary Redus, Von Hayes, and Juan Samuel, while Raines did not have comparable support. The Phillies scored 739 runs as a team, second in the league. The Expos scored 637, tenth in the league. This shouldn't be the criteria for who gets the MVP award.

I'm not criticizing anybody for his vote. I too thought, just looking at the statistics, that Schmidt had had the best year. Raines's remarkable base stealing (70/79) is easy to overlook, particularly when the run count doesn't reflect the advantage. But having looked at the issue more carefully, I now realize that Tim Raines was, in fact, the best and most valuable player in the National League in 1986.

Whew! If you're still with me, give yourself an extra unit of credit. But be prepared for a pop quiz down the road.

1988

In the "Introduction to Player Ratings" in the final Baseball Abstract in 1988, James wrote, "The players . . . will be rated by subjective judgment. Mine. For the past couple of years I've rated players by a poll of the members of Project Scoresheet, but this year I just decided to do it myself."

James changed the format, separating the rankings and comments for the first time. He also combined the two leagues and had one ranking for each position. Raines was rated as the #1 left fielder. The player comments were provided in alphabetical order and letter grades were given as follows:

TIM RAINESHitting for Average: A Hitting for Power: B Plate Discipline: B+ Baserunning: A OVERALL OFFENSE: A Defensive Range: A Reliability: B+ Arm: C+ OVERALL DEFENSE: B+ Consistency: A Durability: A OVERALL VALUE: A- In a Word: Brilliant

James printed a letter that he solicited from Neil Munro, comparing Raines to Wade Boggs. Munro provided a detailed explanation and chose Raines. "As a consequence, if you rate them pretty much even as hitters (with park adjustments) and fielders, you must give the nod to Raines for his baserunning ability."

Earlier in the book, under "Rain Delay," James penned one of his best essays, holding a conversation with himself in the search of the best baseball player in the game. It's a six pager with insightful comments on about 20 players. His conclusion? James ranked Boggs as the best player in baseball, followed by Raines, Ozzie Smith, Don Mattingly, Tony Gwynn, Darryl Strawberry, Dale Murphy, Roger Clemens, Rickey Henderson, and Kirby Puckett.

Although Raines' career lasted until 2002, the Baseball Abstracts were, unfortunately, retired in 1988. However, the Ballantine era books coincided with Raines' first seven seasons (which most would also view as the best seven-year stretch of his career).

Raines. James. Baseball Abstracts. Three of the very best of the 1980s.

* * * * *

Feel free to give James' trivia question from the 1983 comments a shot.

| Baseball Beat | December 27, 2007 |

Four years ago yesterday, I wrote my first article on Bert Blyleven. It was designed to raise the awareness of Blyleven's qualifications for the Hall of Fame. I have added about 20 pieces since then, including more statistical evidence, interviews with Blyleven and voters, and responses to naysayers. Blyleven's vote total jumped from 145 (or 29.2% of the total) in 2003 to 277 (53.3%) in 2006, before retreating to 260 (47.7%) in 2007.

Although Blyleven's support has increased substantially over the past few years, the man who ranks 5th in career strikeouts, 8th in shutouts, and 17th in wins since 1900 is still on the outside looking in. Bert has a long ways to go to make it to the necessary 75% – especially in view of the fact that he will have just four more years left of eligibility after this year. As everyone knows, I strongly endorse Blyleven and will continue to do my part in the hope that the voters will one day see fit to give him his day in Cooperstown.

In the meantime, there is a new player on this year's ballot who deserves to be inducted into the Hall of Fame, yet my sense is that his accomplishments may also be overlooked by the majority of voters. His name? Tim Raines. He wore number 30 on the back of his jersey and went by the nickname Rock. Ergo, 30 Rock, just like the TV series. Unlike the show, this is not meant to be a comedy. The case for Raines is serious and worthy of every voter's time and attention.

A superficial voter may dismiss Raines altogether. "Let's see here . . . 500 HR? Nope. 3,000 hits? Nope. .300 career batting average? Nope. Any MVPs? Nope. Next."

To all that, I say "hold on here." First of all, using Triple Crown stats to gauge the merits of a lead-off hitter like Raines is flat out wrong. He's simply not going to put up magical numbers in HR and RBI. If Raines did, it's unlikely that he would have batted first in 63% of the games he started over the course of his career. Instead, he should be compared to other lead-off hitters.

Isn't it the job of a lead-off batter to get on base and score runs? Well, Raines did both well. Very well. He ranks 40th all-time in getting on base (hits + walks + hit by pitch). Every player who is above him in times on base (TOB) is in the Hall of Fame with the exception of Rusty Staub. Moreover, three of the next four and 23 of the next 27 players on the list behind Raines are also in the HOF. Think about that for a second. Fifty-five of the top 60 players in TOB who are eligible for the Hall have been inducted into Cooperstown. Does Raines, who is virtually right in the middle of this group, deserve to be included among the 92% who are in or the 8% who are out?

Raines also ranks 46th in runs scored. Every player who is above him in R is also in the HOF with the exceptions of Jimmy Ryan, George Van Haltren, and Bill Dahlen – all of whom played a large part of their career in the 19th century. Not one player exclusively from the 20th century ranks higher than Raines in runs and is not in the Hall. Furthermore, the next six and 12 of the next 13 eligible players are also in the HOF. Put it all together and 47 of the top 51 players in R who are eligible for the Hall have already been enshrined. Again, does Raines belong in the 92% who are in or the 8% who are out?

The Rock's rankings in TOB and R alone should basically qualify him for the Hall of Fame with little or no argument. Unfortunately, the voter who pays attention to these two important stats is in the distinct minority. Voters look at hits but how many of them take the time to look at walks? Do walks not count? When it comes to the Hall of Fame, a player would be better served to go to the plate hacking away in hopes of getting a hit because little or no attention is placed on walks.

Had Raines gotten 3,000 hits and walked 935 times rather than accumulating 2605 hits and 1,330 walks, do you think there would be any question as to whether he was worthy of the HOF? I recognize that hits are generally more valuable than walks but the difference is less meaningful for a batter leading off the inning or with nobody on base (unless, of course, the hit goes for extra bases).

Rather than fixating on hits, I suggest we should all pay more attention to times on base and outs. Here is a simplistic way of appreciating Raines' ability to get on base for those folks who don't want to take the time to compare rate stats vs. the league average. Tim's TOB ranking is higher than his PA ranking, while his Outs ranking is lower than his PA ranking. In other words, he got on base more often and made fewer outs than expected given the number of times he went to the plate

TOTAL RANK

PA 10,359 52nd

TOB 3,977 40th

OUTS 6,670 67th

But if one truly wants to compare apples to apples, then it would be best to pit Raines versus other Hall of Fame-caliber lead-off hitters. The good news is that Tom M. Tango has already taken the time to perform this exercise. Tango's conclusion? Raines performed above the level of all Hall of Famers when such players batted in the lead-off spot and at a similar level to Hall-worthy players during the Retrosheet years (1957-2006).

Take a big part of Rickey Henderson and Pete Rose, add a good size part of Lou Brock, Paul Molitor, and Craig Biggio, and stir in some Ichiro Suzuki, Wade Boggs, Joe Morgan, Derek Jeter, and Barry Bonds, and you get a composite that is a shade inferior to Tim Raines.If you have a group of players worthy of the Hall, and an individual player compares very favorably to that group, you have a Hall-worthy player by definition. That is what Tim Raines is: the definition of a Hall of Famer.

Still not convinced? Let's take a look at the three main rate stats (AVG, OBP, and SLG), plus OPS (which is none other than OBP + SLG), and OPS+ (which compares a player's OPS to the league average while adjusting for ballpark effects) for four players. Which player is not like the others?

AVG OBP SLG OPS OPS+

Player A .271 .392 .427 .819 132

Player B .279 .401 .419 .820 127

Player C .294 .385 .425 .810 123

Player D .293 .343 .410 .753 109

Did you say "Player D?" I thought so. That would be none other than Lou Brock, who was voted into the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. The other three players are Joe Morgan (Player A), Rickey Henderson (Player B), and Tim Raines (Player C).

While Raines does not quite match up to Morgan and Henderson, he was closer in value to them than Brock.

All four players rank among the top 11 in career stolen bases. Raines is number one in stolen base percentage among players with 300 or more attempts.

SB CS SB%

1 Henderson 1406 335 80.8

2 Brock 938 307 75.3

5 Raines 808 146 84.7

11 Morgan 689 162 81.0

While on the subject of stolen bases, Raines became the first player in baseball history to steal at least 70 bases in four consecutive years when he swiped 71, 78, 90, and 75 bags in his first four seasons. He extended his streak to six campaigns after stealing 70 bases in 1985 and once again in 1986. Who knows how many bases Raines would have stolen in his rookie year in 1981 had the season not been shortened due to the strike? He stole 71 as is – in just 88 games played (out of a team total of 107).

A cynical voter may also pass on Raines due to the fact that he admitted to using cocaine early in his career. It would be a fallacy given the fact that another cocaine user of the same era was inducted in his first year of eligibility.

AVG OBP SLG OPS OPS+

Raines .294 .385 .425 .810 123

Molitor .306 .369 .448 .817 122

How can one in good conscience include Molitor and exclude Raines? Sure, Molitor's counting stats are slightly better than Raines', primarily owing to the fact that he had 1,801 additional plate appearances. Molitor had 714 more hits but 236 fewer walks while producing 1,370 more outs. To their credit, Raines and Molitor cleaned up their acts and became role models in the later years of their careers. They are both worthy of induction for what they accomplished on the field.

Like Blyleven, Raines played in the majors as both a teenager and into his 40s. At 19, he was the youngest player in the National League when he made his debut in 1979. Twenty-three years later, he was the third-oldest player in the NL during his final season in 2002. Like Blyleven, Raines was also a terrific player from the get go. If not for Fernando Valenzuela, Raines would have been the Rookie of the Year in 1981 when he led the league in SB and placed in the top five in several sabermetric categories, including Runs Created Above Average (RCAA), Runs Created per Game (RC/G), Bases per Plate Appearance (BPA), Offensive Winning Percentage (OWP), and Total Average (TA).

In 1982, Raines led the league in SB and finished in the top five in TOB and triples. In 1983, he led the NL in TOB, R, and SB, while placing in the top five in H, BB, OBP, RC, RC/G, RCAA, BPA, OWP, and TA. In 1984, Raines led the league in TOB, 2B, SB, RC/G, RCAA, and TA, while ranking in the top five in R, H, BB, OBP, RC, and BPA. In 1985, he placed second in TOB, R, 3B, SB, RC, RC/G, RCAA, BPA, OWP, and TA; and third in AVG and OBP.

In 1986, in what turned out to be the best season of his career, Raines led the NL in AVG, OBP, TOB, RC, RC/G, RCAA, BPA, OWP, and TA. He should have been named Most Valuable Player that year but lost out to Mike Schmidt (more on this tomorrow). Tim also ranked 2nd in OPS and third in H, 3B, and SB. It was a remarkable season that was lost on voters perhaps due to the fact that the Expos went 78-83 and finished in fourth place in the NL East, 29 1/2 games behind the New York Mets.

In 1987, Raines led the league in runs scored with 123 even though he missed all of April due to collusion on the part of owners. He returned to Montreal on May 1 after not receiving a single offer from any team at the age of 27 and coming off an MVP-type season. Tim went on to rank in the top five in AVG, OBP, TOB, BB, SB, RC, RC/G, RCAA, BPA, OWP, and TA.

For those first seven seasons, Raines and Schmidt were clearly the two best players in the NL. Raines was every bit as good as Henderson was in those years. He led the league in Win Shares in 1984, 1985, and 1986. Just think what his résumé would look like had he won three consecutive MVP awards!

All in all, Raines had 390 Win Shares, good for 59th all time. (Three WS equals one win. Therefore, Raines was worth about 130 wins during his career.) Using Win Shares Above Bench, Dave Studeman ranked Raines 44th among all position players, post-1900.

Like Win Shares, Wins Above Replacement Value (or WARP3) takes into account defensive value. Raines' 124 career WARP3 ranks 62nd among position players and 83rd among all players (including pitchers).

When you look at all the evidence (including articles by others), Raines is one of the top 50 or 60 position players of all time and perhaps the best lead-off hitter in the history of the National League.

If 30 Rock can win the Emmy Award for Outstanding Comedy Series in its first year, there's no reason why Tim Raines can't be voted into the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.

[Additional reader comments and retorts at the Baseball Think Factory/Baseball Primer Newsblog.]

| Baseball Beat | December 26, 2007 |

Tracy Ringolsby has been a member of the Baseball Writers Association of America since 1976. He has covered the Colorado Rockies for the Rocky Mountain News for more than 15 years. Ringolsby had previously worked for the Long Beach Independent, Press-Telegram (California Angels, March 1977-July 1980), the Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Seattle Mariners, July 1980-July 1983), the Kansas City Star-Times (Kansas City Royals, August 1983-February 1986), and the Dallas Morning News (Texas Rangers, March 1986-1989, and the national baseball writer, 1990-1991).

Born in Cheyenne, Wyoming and a graduate of Cheyenne East High School, Ringolsby and his wife Jane live on 80 acres northwest of Cheyenne with their four horses. Tracy has attended the University of Wyoming in pursuit of the degree he promised his father when he quit school to begin a career in journalism. And what a career it has been. Ringolsby, 56, served as President of the BBWAA in 1986 and was selected by his peers as the recipient of the 2005 J.G. Taylor Spink Award. A co-founder of Baseball America, Tracy has been a member of the Society for American Baseball Research for 28 years.

Born in Cheyenne, Wyoming and a graduate of Cheyenne East High School, Ringolsby and his wife Jane live on 80 acres northwest of Cheyenne with their four horses. Tracy has attended the University of Wyoming in pursuit of the degree he promised his father when he quit school to begin a career in journalism. And what a career it has been. Ringolsby, 56, served as President of the BBWAA in 1986 and was selected by his peers as the recipient of the 2005 J.G. Taylor Spink Award. A co-founder of Baseball America, Tracy has been a member of the Society for American Baseball Research for 28 years.

Ringolsby, who currently sits on the Board of the BBWAA, agreed to conduct a hard-hitting Q&A with me to discuss the organization's policies and procedures in the aftermath of the brouhaha created by the decision to expand membership to baseball writers whose primary forum is the internet. As was the case three years ago when I first interviewed him about his Hall of Fame ballot, Tracy answered every question thrown his way.

Rich: The Baseball Writers Association of America recently voted to open up its membership for the first time to web-based baseball writers. How long has this been in the works and why did the organization decide to allow such writers at this time?

Tracy: It is an issue that has been discussed for close to nine years. As the internet presence grew, and it became as much about reporting news as merely an outlet for opinions and research, the need to address internet writers grew.

Rich: Correct me if I'm wrong here. The admission of internet writers has not only been discussed for a number of years but it was voted down as recently as a year ago. Is the BBWAA guilty of flip flopping or just being slow to accept change?

Tracy: Not at all. The vote a year ago would have included mlb.com on the grounds that the writers are representing the official websites of the teams. When that failed, a revised proposal was adopted that excluded mlb.com, and it passed easily.

Rich: Did the BBWAA establish any guidelines for the admission of internet writers?

Tracy: The same basic guidelines as for newspaper writers.

Rich: Can you share those basic guidelines with us?

Tracy: Off the top of my head, they require a member to work for a newspaper that regularly covers a major league baseball team. Membership is open to full-time employees who are beat writers, feature writers who are primarily involved in baseball coverage, columnists, a cartoonist and an editor from each publication.

Rich: That seems like a strange mix for the Baseball Writers Association of America. "Baseball" and "Writers" should be the operative words here. What's the rationale for allowing columnists, cartoonists, and editors?

Tracy: It probably goes back to the days of formation, but I wasn't alive when the bylaws were written and can only assume the intent. Baseball was by far the premiere sport at that time, and columnists and cartoonists focused on the sport, as did an editor. Ironically, in today's media, most sports sections have assistant sports editors who deal directly with individual sports so I would assume that feeds into the setup. Have some of those areas outlived their purpose? I'm sure they have, but when you set precedents you live with them. It is one reason why whenever I have been involved with a chapter I have been very much in support of a one-year waiting period before applications can be made.

Rich: The BBWAA approved 16 "new" members (out of a total of 18 nominees). However, 14 of these 16 had previously been members, adding to the cynicism of many outsiders who feel as if this was just a token attempt to show progress by a staid organization and that the BBWAA is just another good ol' boys club.

Tracy: Cynicism I think is the correct word. What you have seen is that internet companies have moved to bring in people from the print business to be their reporters and to handle the day-to-day information that they are supplying. As a result, the bulk of those who would have an interest in joining the BBWAA, by their nature, would be former members. I think what the cynics overlook is that if it was merely taking care of the good ol' boys, why was there ever a question about the membership? Many longtime BBWAA members left the organization nearly a decade ago to pursue their current jobs, such as Peter Gammons and Tom Verducci, and, in fact, they have spoken in the past on keeping the membership from expanding because they did not want the organization to lose the focus of its true purpose.

Rich: According to the bylaws, the purpose of the BBWAA is to: (1) insure proper facilities for reporting baseball games, (2) assist in clarifying baseball scoring rules, (3) sustain cooperation and fellowship with the baseball writers of the minor leagues, and (4) foster the most credible qualities of baseball writing and reporting. Have these bylaws changed over the years?

Tracy: Not that I am aware of.

Rich: Bob Dutton, President of the BBWAA, in an interview with fellow Kansas City Star writer and BBWAA member Joe Posnanski, said, "I think it’s easy to see the association exists, primarily, to assist the coverage of baseball print reporters at big-league parks." I have a problem with that statement. I don't see the word "print" in the subsections of those bylaws and only one of the four purposes has anything to do with covering games at big-league parks. It seems to me that the bylaws are actually more accommodating to internet writers than perhaps the Board of Directors and the general membership would care to believe.

Tracy: That is called selective reading, Rich. The organization specifies membership is from newspapers which cover major league baseball on a regular basis, and those bylaws that you are referring to are a follow up on the purposes for the newspapers covering baseball. The membership felt in the changing times it was important to include internet writers in the mix.

Rich: As far as I can tell, Amy Nelson of ESPN and Dan Wetzel of Yahoo were the only newly approved writers who had never been part of the association. First of all, is that true? Secondly, doesn't that seem a bit odd to you?

Tracy: That is true, as far as I know, and no, it is not odd. Amy is not only considered a baseball writer by ESPN but is listed in the Commissioner's media guide as one of the ESPN baseball writers, which would give more credence to what her role at ESPN is. Wetzel is a columnist for Yahoo, and the BBWAA guidelines provide for admission of columnists.

Rich: As has been widely reported and discussed, Keith Law and Rob Neyer were the only two candidates who were denied admission. Can you explain why Keith and Rob were not approved?

Tracy: There were questions about their roles at ESPN, the actual coverage they provided and if BBWAA membership was necessary for them to do their jobs. While I felt both should have been admitted, I do think it is interesting that in submitting the names of writers to be included in the Major League Baseball media guide, ESPN had five different areas in which it was listed and ESPN did not submit the names of Neyer nor Law. The other thing, the BBWAA was not created as a social club. It was designed to work on coverage issues that writers faced. Over the years there have been added items that BBWAA members are involved with but those are added items, not the intent of the creation of the organization.

Rich: Were there questions about the other 16 candidates or were there questions about Keith and Rob only?

Tracy: Actually the questions were not directly about Keith or Rob. The questions were about their coverage aspects. I guess you could get in a debate over what is the difference between covering baseball and writing about baseball. There also was a feeling of trying to avoid setting precedents. I would have to say, however, that to say anything was about any individuals in particular would be unfair. There were concepts discussed, not people. I'd be willing to bet if we discussed the membership on the basis of who was liked or disliked we would have had some serious debates over every candidate (I'm just sort of kidding). Personalities, however, cannot be considered in this type of decision because we are setting precedents for the long-term in terms of membership requirements and there is a need to be careful on matters like that.

Rich: Right. However, Law and Neyer are similar to Wetzel in that all three are baseball columnists. Dan was granted membership but Keith and Rob were not. Does that really make sense?

Tracy: They are not similar from what was said by their employers. As pointed out earlier, ESPN has five different vehicles listed in the Major League Baseball Media Information Directory and neither Law nor Neyer are listed as a baseball writer by ESPN in any of those categories.

Rich: Out of curiosity, what are ESPN's five different vehicles?

Tracy: According to the MLB Media Guide, ESPN is listed under news organizations, publications for both ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia and ESPN the Magazine, television networks, and radio networks.

Rich: With respect to attending games, there is no specific number in the BBWAA's constitution. As such, why did Mr. Dutton and others draw a line in the sand with an arbitrary minimum number of games as a reason for inclusion or exclusion?

Tracy: I think it was a means for trying to provide a guideline. When I first joined the BBWAA, a writer – if he was not a columnist, cartoonist nor editor – had to cover 100 games a year to be eligible. Some chapters have sterner enforcement than others. In Detroit and Colorado, for instance, a writer from a newspaper has to cover baseball for a full year before his membership is considered. That is designed to avoid giving membership to someone who is just passing in the night and doesn't truly cover baseball. Other chapters are more lenient.

Rich: What is the current guideline in terms of number of games?

Tracy: In Colorado, writers have to cover the team on a regular basis.

Rich: You mentioned that Gammons and Verducci were welcomed back to the BBWAA. They are recognized among the best and most popular baseball writers in the business. They performed their jobs as capably as ever the past ten years or so when they weren't part of the BBWAA. Why do they now need to be members "to do their jobs?"

Tracy: This isn't a question of Gammons and Verducci, but rather what they do for their employer. The jobs they do involve being at ballparks and covering the events on a regular basis. And let's face it, there was a segment of the BBWAA that did not feel that any internet writers needed to be members.

Rich: My understanding is that the general membership was presented with a binary choice to either accept the 16 new members or not accept any of them. Is that true?

Tracy: That is not true. The general membership was told it could vote on the applicants individually or as a group, in accordance with the recommendation of the Board of Directors. The membership voted to have the group vote. None of the votes on any of the matters were unanimous.

Rich: Let me ask the question differently. Sixteen of the 18 nominations were recommended for approval by the Board, correct? And the general membership voted to approve all 16 as a group, right?

Tracy: Yes

Rich: OK. If I'm not mistaken, that means the seven-person Board – which consists of you as well as Bob Dutton (President), David O'Brien (Vice President), Jack O'Connell (Secretary), Bob Elliott, Paul Hoynes, and Phil Rogers – made a recommendation not to approve Keith and Rob. Is that right?

Tracy: Yes.

Rich: As with the "yay" vote on the 16 candidates who were approved, the general membership followed the Board's advice and voted "nay" on Law and Neyer. Correct?

Tracy: To split hairs, the membership voted yes on the recommendations of the board.

Rich: Understood. How did you vote?

Tracy: I voted against the Board's recommendation. It was my feeling that all of them should have been admitted. Had we held separate votes on each I would have voted for each. When it was decided to have a mass vote, I voted against it because I did not agree with the proposal. Trust me, this isn't the first time I have voted in the minority.

Rich: Did the membership know that the Board was split?

Tracy: I would assume they did. If there were questions we allow them and none were asked. In the board meeting there were several discussions on matters, including questions about full-time employees and contract employees. Then there was a discussion on the actual coverage requirements. An area that wasn't discussed and may need to be addressed is a difference between covering baseball and writing about baseball. I'm not sure what direction that discussion would take and I do not know if it really matters, but it is an avenue that probably needs to be addressed as the media world changes.

Rich: Absolutely. Thanks to Bob Dutton releasing the badge list earlier this month, we now know that there were approximately 780 active members of the BBWAA as of May 2007. At least 16 more were added at the Winter Meetings. That works out to about 32 per chapter and 27 per team. Maybe the BBWAA has been *too* inclusive over the years, at least with respect to the print media.

Tracy: It isn't about how large the organization is, but rather that the members are involved in regular coverage of major league baseball. I'm not one who feels there is an urgency for size if applicants are not full-time employees involved in regular coverage of baseball.

Rich: Whether these so-called active members are truly active and covering major league baseball on a regular basis is certainly an issue that could – and should – be debated.

Tracy: I don't think you ever stop needing to re-evaluate members to make sure they remain eligible for membership.

Rich: Once a writer is granted membership, does one remain a member as long as he or she continues to pay dues?

Tracy: It is not supposed to work that way. The writer should still have to meet the requirements mentioned above. If they don't, the membership should be dropped. I know several instances of writers who covered baseball for several years, left to cover something else, and when they returned to cover baseball they had to reapply for the BBWAA and they started back at year one in terms of seniority. The Hall of Fame vote and gold card eligiblity, for example, require membership for 10 consecutive seasons.

Rich: Of course, the actives don't even account for all of the members. How many inactive or "lifetime" members are there above and beyond the roughly 800 who are considered active?

Tracy: I couldn't tell you that, but I would say that number is limited. To receive a lifetime membership a person had to be an active member for 10 consecutive seasons, and then needs to apply for that type of membership. It does not provide full membership rights, and in fact there is a specific stipulation that those members, if working on a story, have to contact the local team PR people to make arrangements for access. The lifetime or gold card membership is not active membership.

Rich: Well, by definition, there must be at least 200 retired members. There were 545 Hall of Fame ballots turned in last year and only 300-and-some active members with 10 or more years of experience who were eligible to vote. I know some employers don't allow their employees to cast ballots. Therefore, the number of lifetime members has to be a couple hundred at a minimum. Other than voting for the HOF (which the association itself admits is incidental to being a member), what is the purpose of maintaining this category of membership?

Tracy: To me, it is a manner of respect for long-time members. It allows them to remain a part of the BBWAA, although they are not active and do not vote in matters other than the Hall of Fame, which in reality is an area in which they should be well versed because they have a past history with the game.

Rich: I don't have a problem with that per se, although I'm still confused about the merits of columnists, cartoonists, and editors whose main job was/is not writing about baseball. There seems to be an inconsistency here. On one hand, we're told that membership is only for those who attend games on a regular basis because they need credentials to get into the press box and the clubhouse. On the other hand, we've learned that there are numerous members who never really covered baseball at all. Am I missing something here?

Tracy: I must be missing something. Can you tell me the numerous members who never really covered baseball at all, other than columnists, cartoonists or editors, who have membership under their own job description? I'm not aware of those folks.

Rich: We must not be on the same page. I'm not referring to the beat writers. Instead, I'm actually talking about columnists, cartoonists, and editors. For example, John Feinstein is a top-notch sportswriter, but he's not really a baseball writer.

Tracy: Rich, I do believe he actually covered baseball briefly at the Washington Post and then became a columnist at the Post. I cannot swear as to what his exact position was. It does, however, seem that when Tom Boswell moved into a columnist role, Feinstein was involved in the coverage of the Orioles for the Washington Post. That aside, as I said there are provisions for columnists, cartoonists and an editor. I'd have to know the ones you are referring to in regards to the "numerous'' members who never really covered baseball. In reality, many of the columnists did at one point cover baseball as a beat. Have there been oversights in some instances or guys who might have slipped by for some reason that I do not know or can't explain? I would imagine so. Does that make it right? No. Does that mean there should be oversights in the future? No.

Rich: Unfortunately, this isn't the forum to go over the qualifications of each and every member. That said, I appreciate your time and willingness to discuss the purposes of the BBWAA and the guidelines for membership. I think we have covered a lot of ground in our Q&A. You've been a member for over 30 years – and a highly distinguished one at that – and, believe me, I applaud your efforts to open up the membership to baseball writers whose medium is the internet. I think more reforms are needed, but this is a good first step.

Tracy: There are always things that need to be fined tuned and addressed. This year's decision on internet membership was a step in that direction. Do things need to be adjusted? Certainly. The sad part was the decisions this year were turned into a personal issue by some and I can honestly say personalities weren't involved in the decision-making process. It was more a concern of trying to avoid setting precedents and wanting to obtain further information in some cases.

Rich: I hope that the BBWAA continues to revisit rules that appear to be somewhat antiquated in the spirit of advancing the profession while doing what's best for the game, including making its awards and Hall of Fame balloting as relevant as possible.

Tracy: I think any profession has to constantly look to move forward. I would say the intent is to make sure that the BBWAA awards and Hall of Fame balloting remain as relevant as they are. I don't see where they can not be considered as relevant as possible. If they were irrelevant there would not be as much attention focused on them. I do think, however, that any selection process will have its flaws because it is rarely, if ever, unanimous and those with dissenting opinions usually make the most noise. What I am proudest about with the Hall of Fame voting – and it was being done long before I cast my first vote – is that the discussions center on who should be in unlike Hall of Fames in other sports where there is a lot of time spent trying to justify who was selected.

Rich: Speaking of which, who are you voting for this year?

Tracy: Alphabetically, Bert Blyleven, Dave Concepcion, Rich Gossage, Jack Morris, Lee Smith and Alan Trammell. The biggest debates for me were Tim Raines, who obviously was overshadowed by Rickey Henderson, but also if you take Vince Coleman's five top years, I would say he outperformed Raines, too, and I don't see Coleman as a Hall of Famer.

The three I wrestle with are Andre Dawson, Dale Murphy and Jim Rice, in that order. I just see them overall as very similar players, and I have a very difficult time putting a marginal defensive player (Rice) in the Hall of Fame. I know there are a couple who are in, but I didn't vote for them and rather than considering them precedents I would rather consider them isolated incidents. The same with Don Mattingly. As much as I admired him as a player, I just don't see his numbers for a corner bat opening the door to Cooperstown. I'm also one of those who doesn't project what could have been. If a career is cut short, I consider that the career because we don't know what would have happened had the player remained healthy. Murphy is probably the best example of that. Had his career been cut short by four years I think he would have had strong support because people would have made their statistical projections and his career numbers would have been better than they actually turned out to be.

Rich: You sent me an email last year, saying that you had come around on Blyleven. I commend you for being open minded on the subject and changing your vote. My next project is to have you see the light on Raines. I would be remiss if I let the comparison to Coleman go by without comment. Yes, they both played left field, led off, and stole a lot of bases. But, other than that, the difference between Raines and Coleman is like night and day. Raines hit .294/.385/.425; Coleman, .264/.324/.345. That's 141 points of OPS. Over the course of their careers, Raines got on base twice as often and had twice as many total bases as Coleman.

I know you referenced their top five years, but the truth is that Raines (.334/.413/.476 with an OPS+ of 151) was a much better player than Coleman (.292/.340/.400 with an OPS+ of 104) at their respective peaks, too. I don't think the five-year numbers are much different. We agree on Coleman. He's not a Hall of Famer. But we disagree on Raines. I believe he is very worthy. I hope you keep an open mind on Raines and give him a closer look next year.

Tracy: That's probably not the only one we disagree on. Raines will have to get in line for me, behind Dawson and Murphy and Rice, while I still try and sort those three out. I know there is support for each of them, but I guess what I have the hardest time dealing with is why Rice's support seems stronger when I would put him third out of the three, and I'm not convinced yet on any of the three. Now that's where a vote gets difficult because I have so much respect for the people that Dawson and Murphy are that it is hard not to put them on my ballot.

Rich: Thank you for taking the time to go over these issues, Tracy. I appreciate your candidness in explaining the BBWAA's policies and procedures and for sharing your personal views on these subjects.

Tracy: Hopefully, it will provide some insight. I don't think anyone felt that the decisions this year were the end alls in dealing with the internet, but rather a first step.

[Additional reader comments and retorts at the Baseball Think Factory/Baseball Primer Newsblog.]

| Command Post | December 23, 2007 |

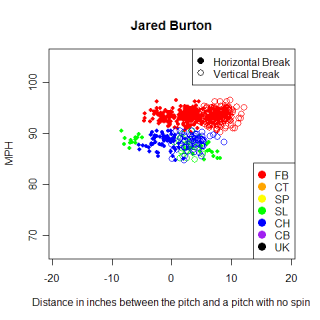

John Walsh wrote a fantastic piece on Thursday about the differences between fastballs, sliders, changeups and curveballs, and what happens when those pitches are put in play. I've done some research into this area myself and wanted to graphically present some of my findings.

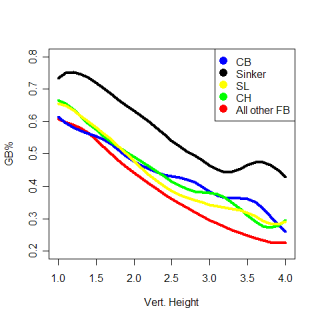

One point that John made was fastballs, especially non-sinking fastballs, are hit on the ground the least often of any pitch. You can take this a step further, and look at the impact the location of a pitch has on how it is hit. The graph below looks at the percentage of each pitch type that are hit on the ground at different heights.

The most obvious thing is the huge advantage a sinker has in generating grounders compared to any other pitch. (I found sinkers the same way John did, by using all pitches with a pfx_z value of less than 6 inches). This isn't surprising, but what was a little surprising to me is how the groundball percentage of every pitch decreases at almost the same rate with increasing height. I would have thought that certain pitch types, especially curveballs, would have been much better, relative to other pitch types, when they were thrown low in the zone vs. high in the zone. I thought a curve would have a higher ratio of gb% on low pitches to gb% on high pitches than other pitch types did. This wasn't the case, so maybe the idea of a high curveball being a terrible pitch isn't totally accurate.

To get a better idea of what happens to high curveballs (and all pitch types), I looked at the slugging percentage for balls in play (including homers) based on which region of the strike-zone the pitch was thrown to. The table below shows those slugging percentages for the three vertical sections of the strike-zone. (The averages at the bottom are only for the pitches in the strike-zone and are higher than the averages in Walsh's article.)

FB SL CH CB Sinker | Avg.

Top 0.564 0.565 0.692 0.579 0.580 | 0.596

Middle 0.622 0.590 0.612 0.559 0.558 | 0.588

Bottom 0.554 0.496 0.498 0.458 0.481 | 0.497

==================================================

Avg. 0.580 0.550 0.601 0.532 0.540 | 0.561

For pitches low in the strike-zone, batters have the lowest SLGBIP against curveballs, but if a curve is thrown at the top of the strike-zone, batters greatly increase their SLGBIP. Curveballs are hard pitches to hit, but the difference in SLGBIP between a low curve and a high curve is second only to the difference between a low changeup and a high changeup. Everything else being equal (speed, spin, movement, expectations of the batter, if the batter swings, etc.) a pitcher is increasing the batter's SLGBIP by roughly .100 points if he throws a curveball that isn't at the bottom of the strike-zone.

A changeup is potentially a great pitch, but changeups that aren't at the bottom of the strike-zone are hit much better than average. Low changeups are hit about as well as low sliders, but as the two pitches are elevated, the changeup gets hit much harder than the slider. A changeup above the knees is essentially a meat-ball and by throwing a changeup that isn't down in the strike-zone, the pitcher is increasing the batter's SLGBIP by at least .115 points.

| Past Times | December 18, 2007 |

Looking ahead to 2008, the top American League teams - the Red Sox, Tigers, Angels, Indians and Yankees - are also the five best squads in the majors. If all goes as is widely expected, one of these teams won't qualify for the postseason despite their elite status.

With the possible exception of the Mariners sneaking into the playoffs if the Angels have an unexpected collapse, it seems that the playoff prospects for the other eight AL teams are somewhere between slim and none - and slim just left town. What's a general manager of a mediocre-to-poor team supposed to do when confronted with this harsh reality?

Barring a baseball miracle such as the A's or Twins pulling off more of their low-budget magic, there are two clear paths that a small-market or losing AL team can take in '08. The best long-term option may seem like waving the white flag, but it makes sense from an economic and future-oriented perspective.

Should a less competitive team go for broke (literally) and spend $90 to $110 million on payroll in a desperate attempt to reach the .500 level? I'd hate to have to build a marketing campaign on "81 wins in 2008 is great!" How many more tickets will the Blue Jays, Orioles, Rays or Rangers sell if they win 78 games instead of 73?

GMs and front offices throughout the league should have made this decision by now. Without a firm and solid plan, just about every team in baseball except for the miserly Marlins has a knack for doing the drunken sailor routine when the mid-level player of the day hits the free agent market.

The Royals are this year's most obvious example of desperation winning out over logic and common sense. A $36 million commitment (three years at $12 million/season) to Jose Guillen is a prime example of what not to do when trying to improve a losing franchise.

While Guillen has some pop in his bat and a strong arm in rightfield, his reputation for being a perpetual pain in the rear is just what a team doesn't want for the long term. It also remains to be seen how Guillen will do without the "performance-enhancing substances" (English translation: steroids) that may cost him a 15-game suspension.

Guillen might be just the right five or six-hole hitter to help a contender in a supporting role. For the losing, cash-strapped Royals, he's a financial vampire draining the team's meager payroll. No one in Kansas City lined up for season tickets or playoff seats when Guillen's signing was announced.

Numerous examples of such short-sighted thinking (remember Franklin Stubbs, Pat Meares, Derek Bell and Adam Eaton, to name just four?) can be found in the free agency era. Earl Weaver and the late 1970s Orioles had perhaps the most intelligent approach to playing the free agent game.

To paraphrase Weaver, "Unless a guy has a strong chance of going into the Hall of Fame, don't get in a bidding war for him." During that time, the Orioles picked up role players and second-tier pitchers at modest prices. Free agency wasn't an expensive roll of the dice, but a way to fill some holes and find a bargain or two.

So how much revenue does a team forfeit by going from mediocre to worse? If attendance drops 100,000 when a team falls from the previous example of 78 to 73 wins, it could mean a decline in gross revenue of $3 million to $3.5 million.

But what if that same team could shave $20 million from the payroll for a slightly worse record? Why pay a journeyman $4 million to $6 million for a 70-RBI season when a cheap $1.5 million platoon might produce 63 RBI? That extra bit of production can be mighty expensive. Seven extra RBI could mean the playoffs for a contender, but that doesn't apply in the nether regions of the standings.

Losers also get higher draft picks and possibly more revenue sharing, so not going all out for a possible shot at .500 has some logic from a financial perspective. This is not to suggest that any team throw games, but a look at the realities of modern baseball economics.

This hypothetical scenario doesn't work if team owners pocket the extra $16.5 million or more that could be gained from taking the frugal road. It makes sense only if the savings are heavily invested in player development and scouting with a goal of future success.

If a franchise chooses this route for a year or two, they also need to take good care of the fans. Offer tons of otherwise unwanted tickets at big discounts - say $5 each - when the Rays and Pirates come to town. It's good PR and customer relations, not to mention a way to get kids and folks with modest incomes into the park.

Think like master promoter Bill Veeck and give away a few free cars or vacations. Have an unannounced gift like a free soda to everyone who comes to a game on a blazing hot day. Pepsi and ice are cheap, and the gesture will be remembered.

Three of the four teams in the 2007 League Championship Series - the Indians, Rockies and Diamondbacks - had some of the lowest payrolls in the majors. They have surged from sub-.500 seasons through developing their own talent at the minor league level.

Ideally, low-budget teams should do everything they can to develop pitchers both for the major league roster and as a valuable trading commodity to fill weak spots. Electric arms will always be in short supply, but any GM with a suplus of young middle relievers (now fetching $4 million to $5 million/year as free agents) and 3, 4 and 5 starters is going to be extremely popular at the winter meetings.

Getting back to the much-maligned Marlins, how many team owners would trade their undistinguished records of the past 15 years for Florida's two world championships since entering the majors in 1993? A pair of great seasons and a bunch of lousy ones may have more appeal than occasional blips above the .500 level and a string of false hopes.

Putting together a team that can take the World Series or compete for a few years is one thing. Keeping that roster together in the long run, paying ever-escalating salaries for essentially the same production and bidding for free agents isn't an option for small-market franchises. In those instances, it could make sense to exchange one step back in 2008 for three steps forward later.

| Baseball Beat | December 17, 2007 |

Dan Lewis from ArmchairGM recently invited me to participate in The 2008 Baseball Hall of Fame Ballot -- A Roundtable Discussion.

David Pinto of Baseball Musings, Dayn Perry of FOXSports, Dan McLaughlin of Baseball Crank, and Matt Sussman of Deadspin were the other guests. The five of us were asked "to pick one guy to enshrine and one guy to leave out, and write an essay for each." I chose Bert Blyleven and Jack Morris (I'll let you guess which one I elected to support). Sussman took the opposing viewpoints.

Here is what I had to say about Blyleven: