| Touching Bases | March 31, 2009 |

“My guess is that we will see another Triple Crown winner in the next ten years. The historical trend lines are heading in that direction. That doesn’t necessarily mean anything, as, as I said, the historical trend lines may be simply a result of a random clustering of talent. It’s difficult, and it hasn’t happened for a long time, but it has not become impossible for some player to win the Triple Crown.” Bill James—June 6, 2008

Albert Pujols has a serious shot at winning the first Triple Crown since Frank Robinson and Carl Yastrzemski did so back in the 60s. It's been over 70 years since a National Leaguer led the league in home runs, batting average, and runs batted in. The only time Pujols has led the league in any triple crown category was when he boasted a .359 batting average back in 2003. He’s finished second in every category at least once. But this year might be different.

This year, Pujols might have a fully healthy elbow. This year, Chipper Jones might not threaten .400. This year, Ryan Howard might not pound 50 home runs. According to Joe Posnanski, you just have to have The Power to Believe. This is the year of Pujols.

Here's how Pujols has stacked up thus far in his career. This table shows Pujols' marks followed by the league leader's in parentheses.

+-------+-------------------+-----------+----------------+-------+-------------------+ | Year | Batting Average | Home Runs | Runs Batted In | Games | Plate Appearances | +-------+-------------------+-----------+----------------+-------+-------------------+ | 2008 | .357 (.364) | 37 (48) | 116 (146) | 148 | 641 | | 2007 | .327 (.340) | 32 (50) | 103 (137) | 158 | 679 | | 2006 | .331 (.344) | 49 (58) | 137 (149) | 143 | 634 | | 2005 | .330 (.335) | 41 (51) | 117 (128) | 161 | 700 | | 2004 | .331 (.362) | 46 (48) | 123 (131) | 154 | 692 | | 2003 | .359 (.359) | 43 (47) | 124 (141) | 157 | 685 | | 2002 | .314 (.370) | 34 (49) | 127 (128) | 157 | 675 | | 2001 | .329 (.350) | 37 (73) | 130 (160) | 161 | 676 | +-------+-------------------+-----------+----------------+-------+-------------------+

Let’s break it down by category. I've looked at six projection systems—Bill James, CHONE, Marcel, Oliver, PECOTA, and ZiPS—to give us an idea of what to expect.

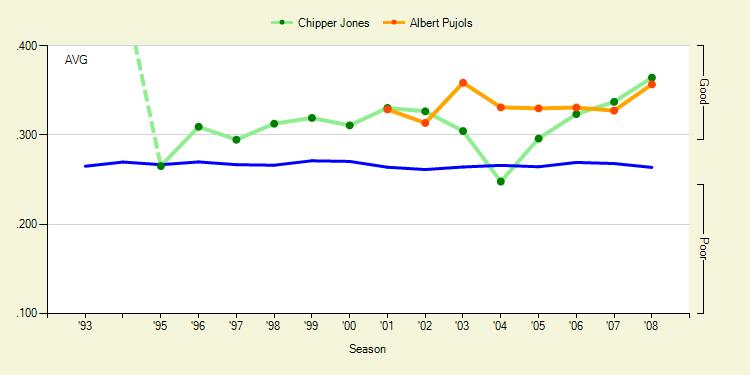

Batting Average

Last year, Chipper Jones'.364 average narrowly edged Pujols’.357 average for the batting title. This year, every projection system shows Pujols consistently hitting between .327 and .339. Chipper has a much wider range. CHONE and PECOTA, currently the two most trusted systems out there, completely disagree on Chipper. CHONE puts him at .310 while PECOTA shows Jones posting a .341 average to edge out Pujols. Jones’ true talent level with regards to batting average was the subject of much discussion here, here, and here. It's tough to say who has the edge between the two.

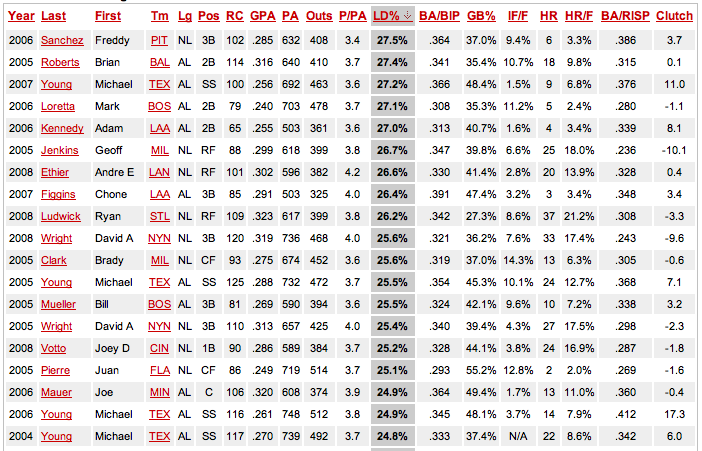

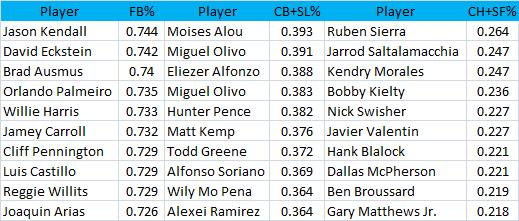

Pujols and Chipper both excel in their plate discipline skills. Last year they had the lowest first-strike percentage of all National League batters to qualify for the batting title. They rarely see pitches inside the strike zone, and neither is prone to swing at pitches in general. In fact, Pujols and Chipper both walked more than they struck out. Pujols has achieved this feat seven straight years. When shooting for a high batting average, the importance of not striking out is, of course, that one has a greater chance at getting a hit if the ball is put into play.

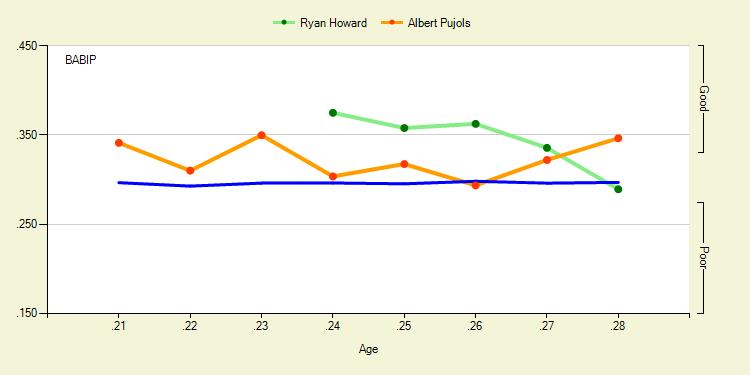

Chipper and Pujols also excel at earning surefire hits by putting the ball out of play and over the fence. Low strikeout and high homerun totals give players a good chance at having a high average. The rest is dependent on BABIP. The factors that go into BABIP, according to an article by Peter Bendix and Chris Dutton, boil down to pitch recognition, speed, the ability to make solid contact, and the ability to spread the ball to all fields. Pujols hits a lot of line drives (20% career), and has incredible power (22.7% HR/FB, 84 XBH/year). He rarely swings, but when he does swing, he makes contact 90% of the time, which is above average and exceptional for someone who swings so hard. However, Pujols doesn’t spray the ball particularly well and isn’t too fast down the line. (He’s not slow, though. Fans gave him 46 out of 100 on speed, he’s an average to good baserunner, and he has a great glove.) Overall, xBABIP says that Pujols has gotten very lucky with BABIP lately, but nevertheless, Pujols' best shot at any of the categories is in batting average, where he and Jones are almost in a class by themselves.

Other batting average contenders: David Wright and Hanley Ramirez project to hit better than .300 almost across the board. Their problem is that they strike out too much, having both eclipsed the century mark last year. Garrett Atkins. Milton Bradley. Matt Kemp, if his .376 career BABIP is sustainable. Chase Utley. Jose Reyes. Brian McCann. Manny Ramirez has a hitter's haven in Los Angeles. Pablo Sandoval is my sleeper.

Home Runs

Ryan Howard is going to be Pujols’ biggest challenger in home runs and runs batted in. Howard, unfortunately, simply is more one dimensional than Pujols. There are no average specialists like Ichiro is in the AL, but Howard is the National League specialist in hitting the ball a long ways. A third of his fly balls clear the fence. Howard has hit 48, 47, and 58 long-balls over the last three years. Not a single projection system has Pujols hitting greater than 41 homers. Meanwhile, not a single projection system has Howard hitting fewer than 40. But there is hope.

Looking at their skillsets, Pujols may actually be the better homerun hitter, but is simply in worse circumstances. If we can establish that he has a higher talent level when it comes to homers, I say we can at least give him a legitimate shot to take the category.

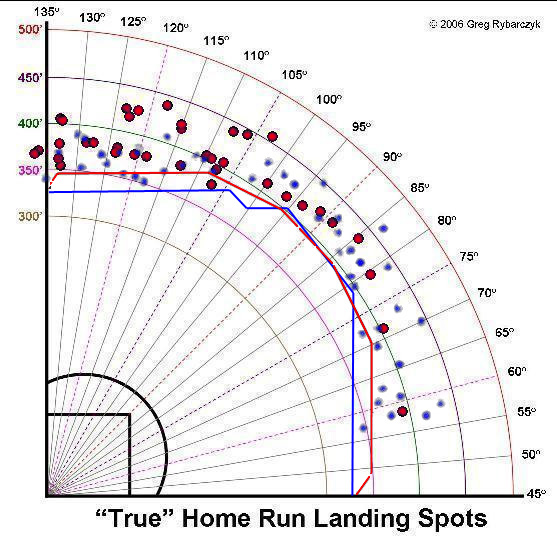

Howard’s home park is hugely beneficial to his power output. Statcorner’s park factors show a crazy 116 HR/FB park factor for Philly and an equally ridiculous 87 HR/FB for St. Louis. (That’s Petco level. I had no idea.) Greg Rybarczyk used his Hit Tracker system to come up with a new method for calculating home run park factors. Howard is 15% more likely to hit homers in Citizen Bank Park to any field except for straight away center, where Pujols would have an edge.

Howard’s average homer traveled 400 feet last year and the speed off bat was 104 MPH. But Pujols demonstrated more raw power, as he hit his average homer went 406 feet and 106 MPH off the bat. Furthermore, Howard's power figures seem to be declining, as his distance and speed figures are trending downward. Pujols shows more consistent power, averaging distance and speed off bat figures of 406, 412, 407, and 106, 109, and 110 in past years.

Here's the placement of their home runs from last year. Pujols' home runs and Busch's outfield walls are in red, Howard's home runs and Citizen Bank's outfield walls are in blue.

See that 20 foot discrepancy between Busch's left field wall and Citizen Bank Park's? It looks like Howard got three or four extra homers in that area, and there's little doubt in my mind that Pujols hit some fly balls out there that went for mere doubles.

Other home run contenders: Adam Dunn won the "golden sledgehammer" with an average of 419 feet and 109 MPH. Fortunately for Pujols, he's now playing in Nationals Park. Four straight seasons of exactly forty homers will likely come to an end. Ryan Braun and Prince Fielder are The Brewers Young Duo That Needs A Nickname. They're 24-25 years old and Fielder's already logged a 50 home run season while Braun's getting there. Joey Votto. Lance Berkman. Adrian Gonzalez was just profiled by Marc Normandin on Baseball Prospectus using Hit Tracker data, and it's crazy to think what he'd be hitting if he were still in Texas. Manny Ramirez. Alfonso Soriano. Chris Young is my sleeper, and who knows what Justin Upton is capable of?

Runs Batted In

Ryan Howard is out in front of the RBI race, but we all know how team-dependent those are. Last year, Chase Utley made up 32 of Howard's 146 RBI, but if Utley is dinged up, his decline, coinciding with Howard’s decline, would severely impact Howard's RBI potential. PECOTA, in fact, shows Pujols driving in more runs than Howard.

Last year, Pujols batted 3rd behind Aaron Miles and Skip Schumaker, who did well getting on base in front of him. Schumaker should bat leadoff this year, which is a plus, since he's OBPed around .360 the last couple of years and upped that to .370 last year when he was the leadoff man. Hopefully Ryan Ludwick bats second, which would give the Cardinals' top two batters higher OBPs than the Phillies top two of Jimmy Rollins and Shane Victorino. Pujols batted third most of last year, but it looks like Tony La Russa will switch Pujols to cleanup and insert Ryan Ankiel into the three hole. The trio of Schumaker, Ludwick, and Ankiel ought to set the table nicely for Pujols, at least better than did Miles, Schumaker, and Cesar Izturis, who La Russa batted ninth most of last season season in place of the pitcher.

Of note, Howard had fewer extra base hits than Pujols, despite all the homers. The lack of doubles is a large part of the reason why Howard is overrated. Howard had 146 RBI to Pujols’ 116. They both earned just over half their RBI on homers, but Howard was able to earn twice as many RBI on singles, while hitting thirty fewer singles. This suggests Howard had men in scoring position more often than Pujols did. Indeed, Howard had 50 more plate appearances with runners in scoring position. Perhaps that evens out this year.

Pujols has been getting intentionally walked more and more, and last year was given a free pass twice as often as Howard. That doesn't bode well for Pujols, considering all those walks come during RBI chances. Furthermore, Howard’s BABIP with RISP was .383 compared to an overall .285 BABIP. This is likely explained by the infield shift, as Rich Lederer noted last year. On the other hand, Pujols faced terrible luck in RBI situations, suffering a BABIP with RISP 50 points below his season total. Check out this graph from fangraphs, and first off notice the age. Ryan Howard is older than Albert Pujols! Again, I had no idea.

If Howard can't collect hits within the field of play, and continues his strikeout percentage trend, he'll simply be relying on his homers for RBI. I've already shown that that faucet of production might run drier for Howard than it has in previous years. Howard has a strikeout percentage three times that of Pujols, and when they swing, Howard swings and misses three times more often too. Howard's skills are in decline. I’m going to say there’s a chance for Pujols to out ribeye Howard.

Other RBI contenders: David Wright, Carlos Beltran, and Carlos Delgado. The top of the Mets' lineup is really dangerous. Lance Berkman. Manny Ramirez. Joey Votto. Aramis Ramirez. Braun and Fielder. Garrett Atkins. Andre Ethier is my sleeper. The top of the Dodgers lineup is awesome too, and Ethier slugged .510 last year. If Adrian Gonzalez were to get traded, he could compete, but the Padres aren't scoring many runs this year.

In my opinion, Pujols is the best hitter for average, best hitter for power, and best hitter at driving in runs in the National League. The problem is that the pieces around him have yet to fall perfectly into place. His park, his lineup, and other Triple Crown category contenders have not been kind to him. I won’t predict that Pujols wins the Triple Crown, if only for the fact that no matter how overwhelming a favorite is in any category, the field is generally a better play thanks to random variance. But if Pujols does pull it off, don't tell me I didn't warn you.

| F/X Visualizations | March 30, 2009 |

In this post I continue, and finish, my series deconstructing the pitch specific run value maps that I first presented here. In the first entry I broke down the different events that contributed to the run value maps for fastballs, here I will do the same for the remaining three pitches I looked at: curveballs, changups and sliders.

Recall, from the fastball post, the methodology I use:

The run value of a pitch is determined by the outcome of four events.

- If the batter swings at the pitch or not.

- If no to 1, whether the taken pitch is called a ball or a strike.

- If yes to 1, whether the batter makes contact.

- If yes to 3, the run value of that contact.

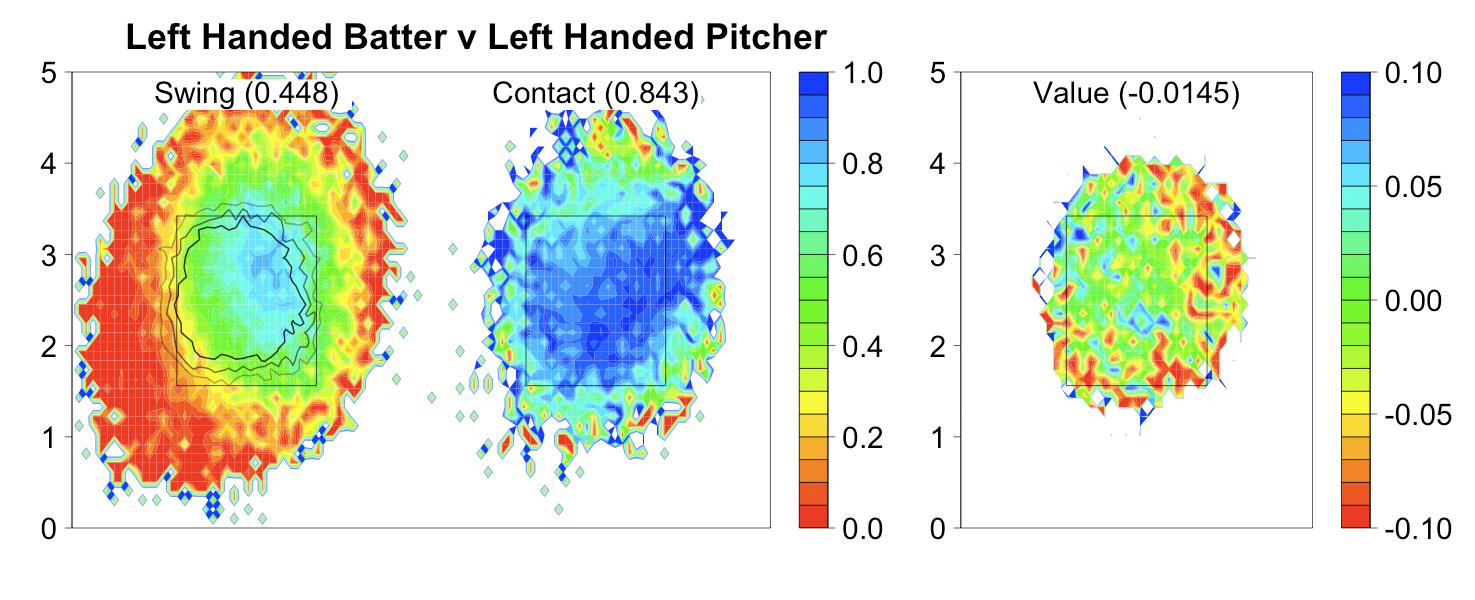

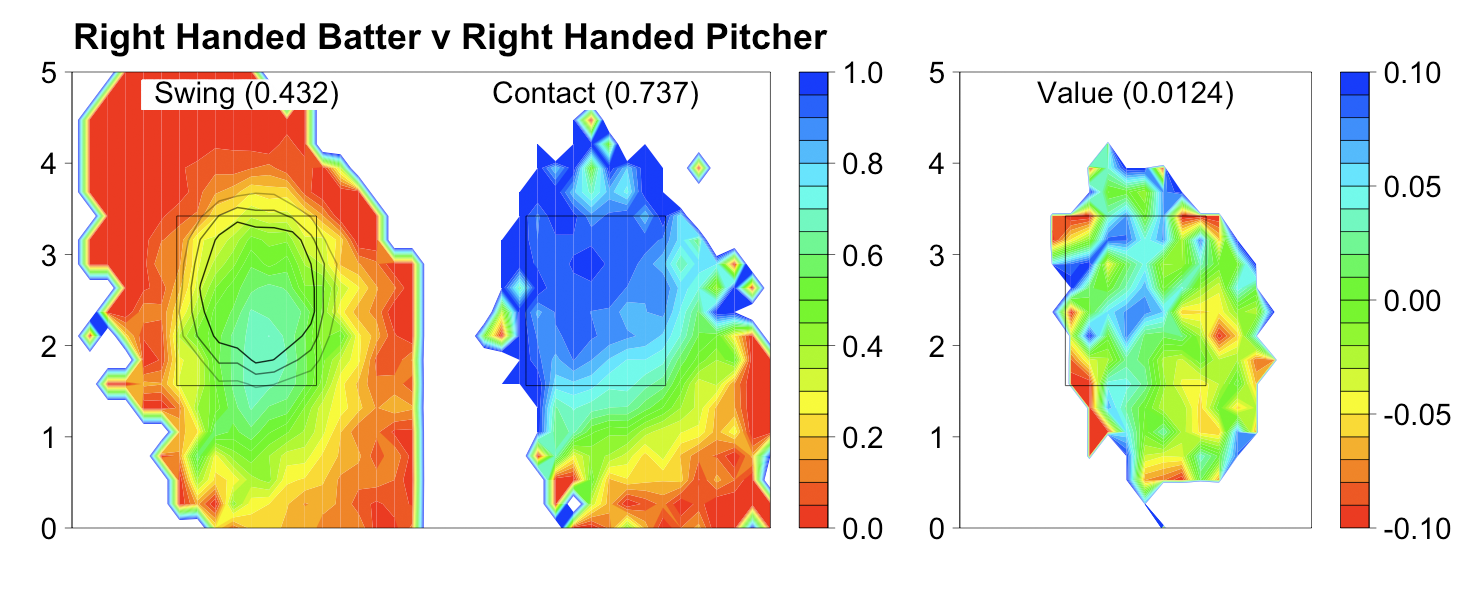

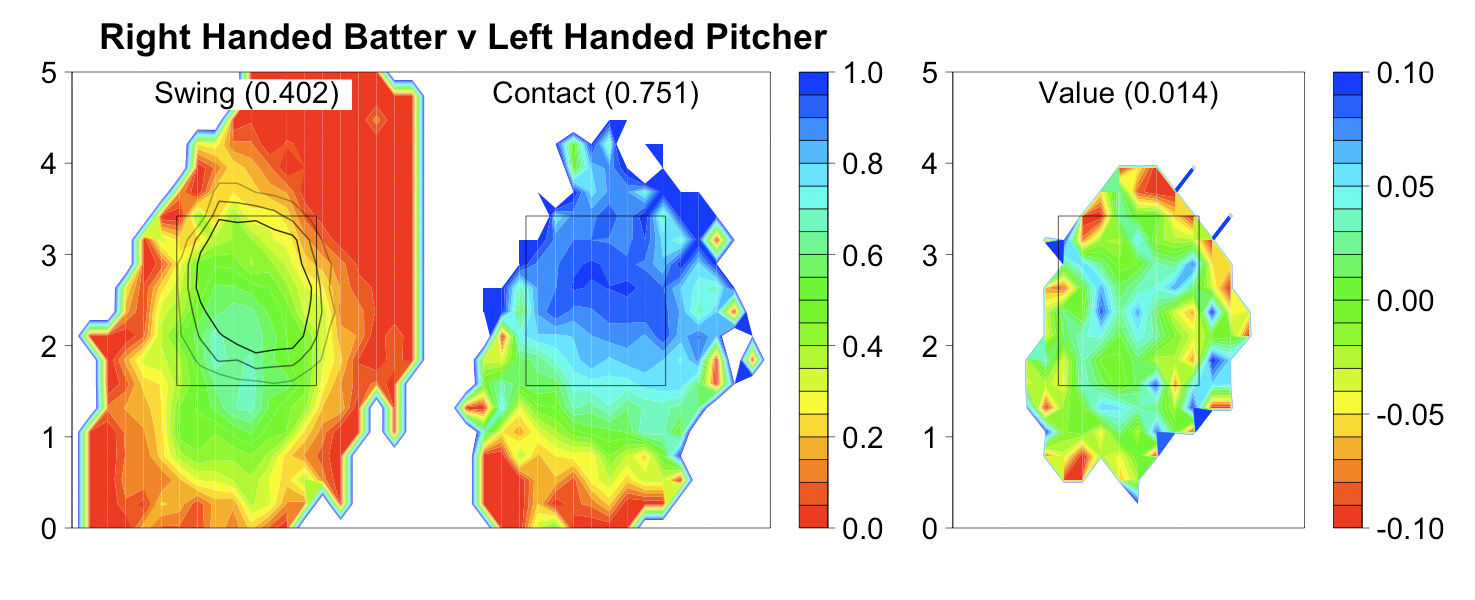

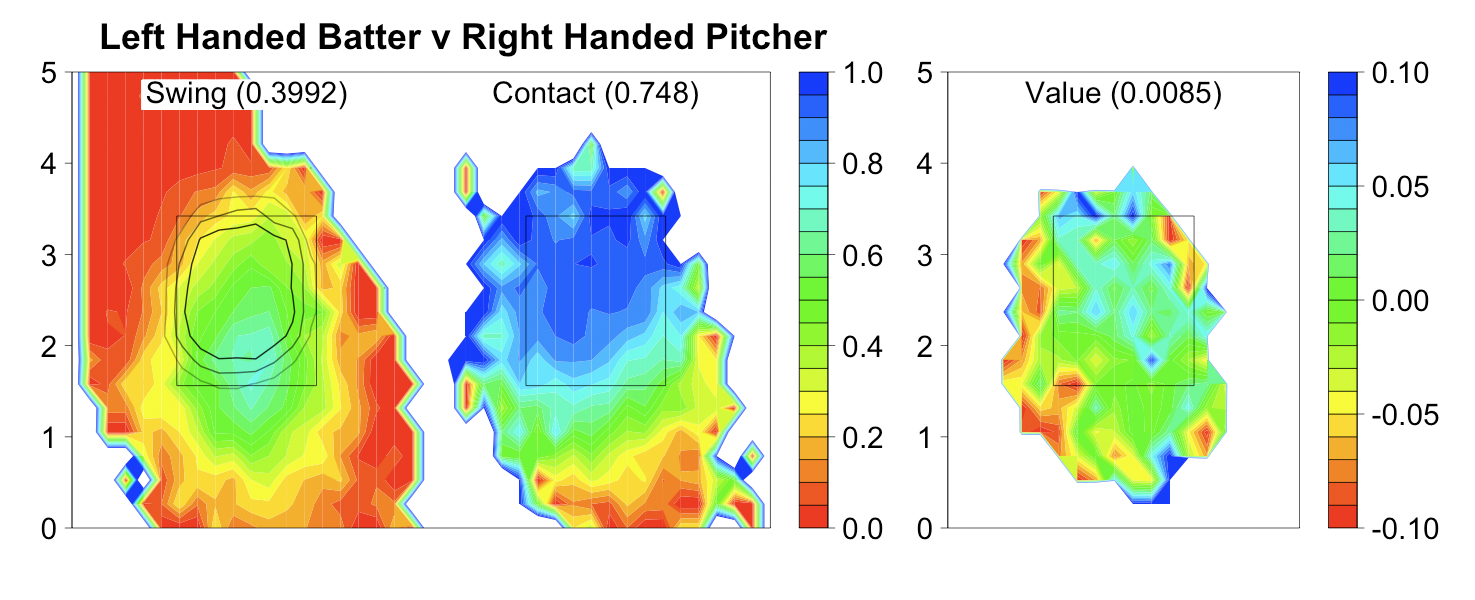

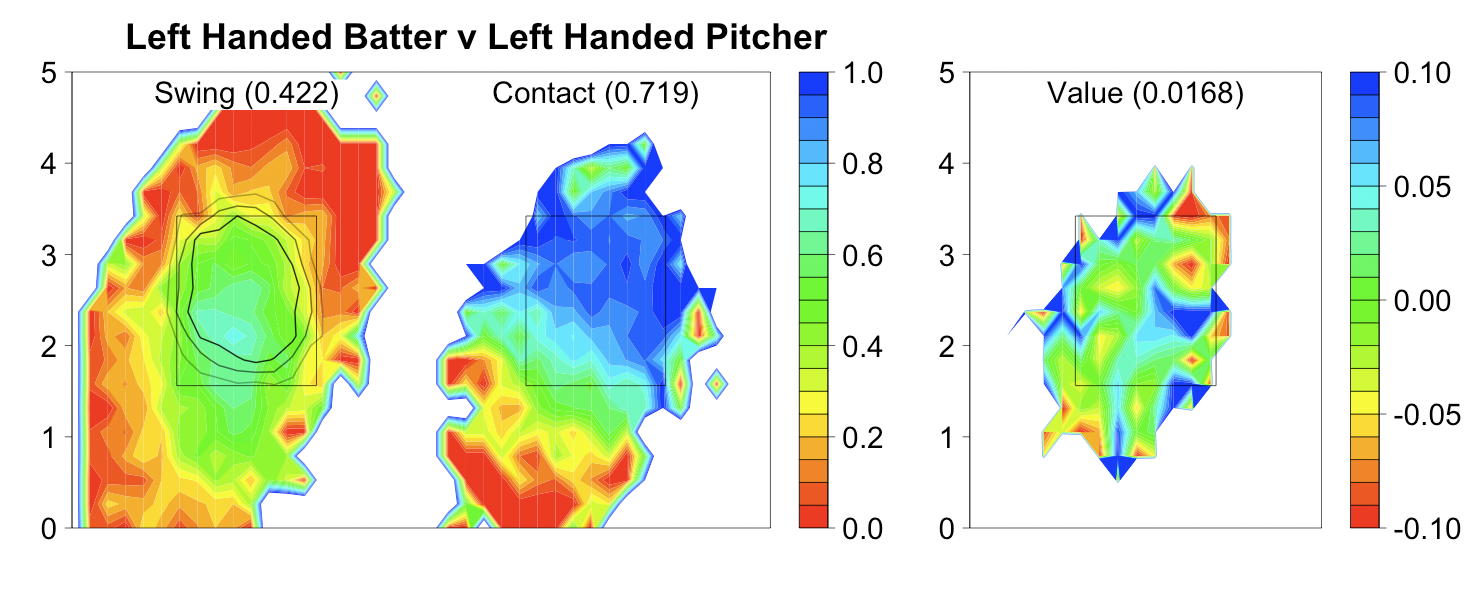

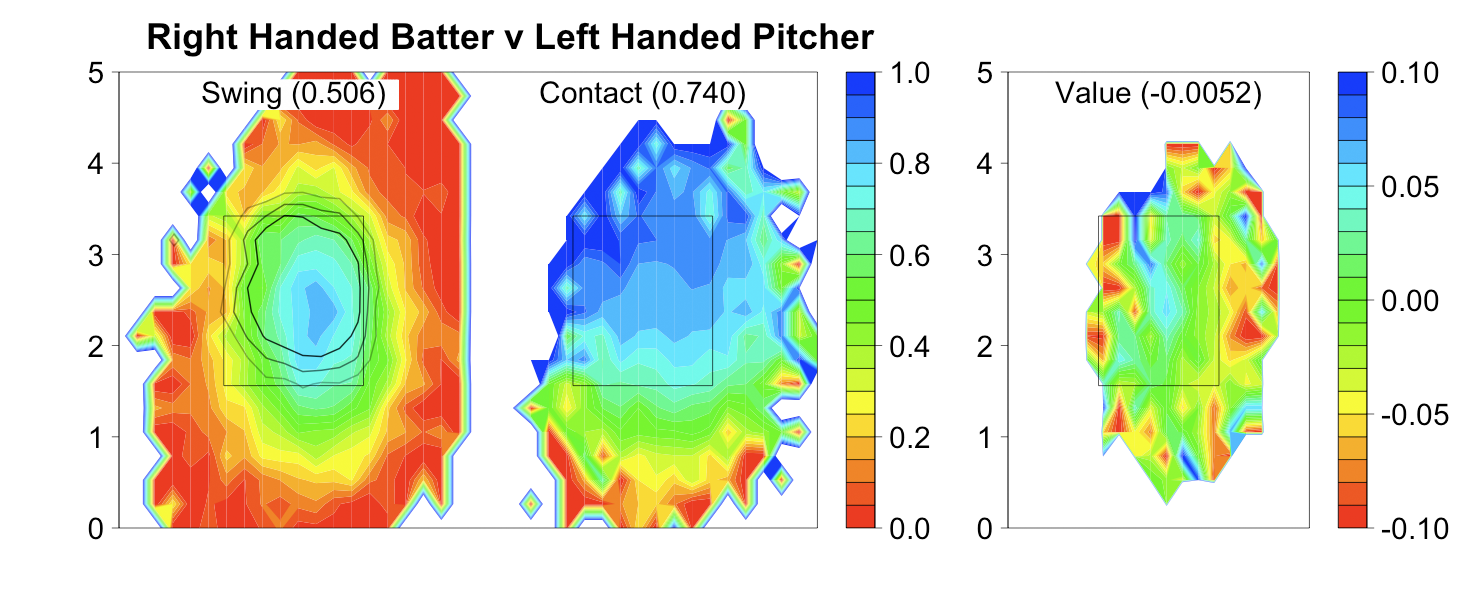

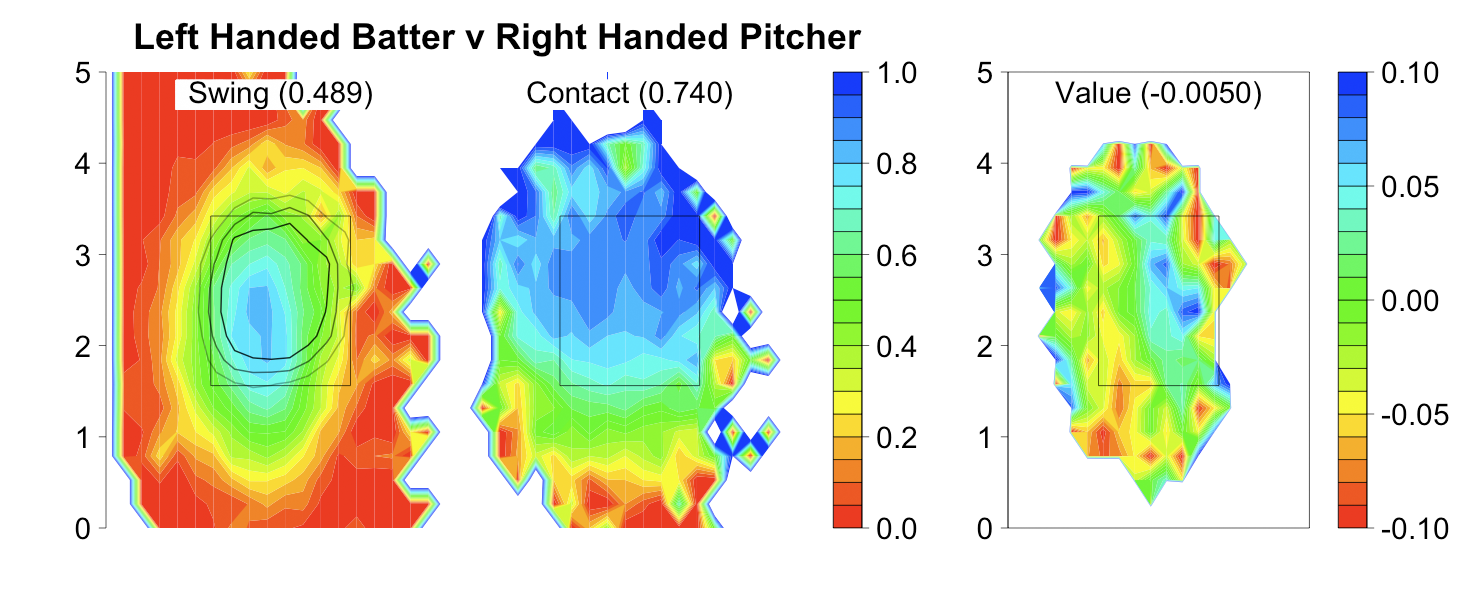

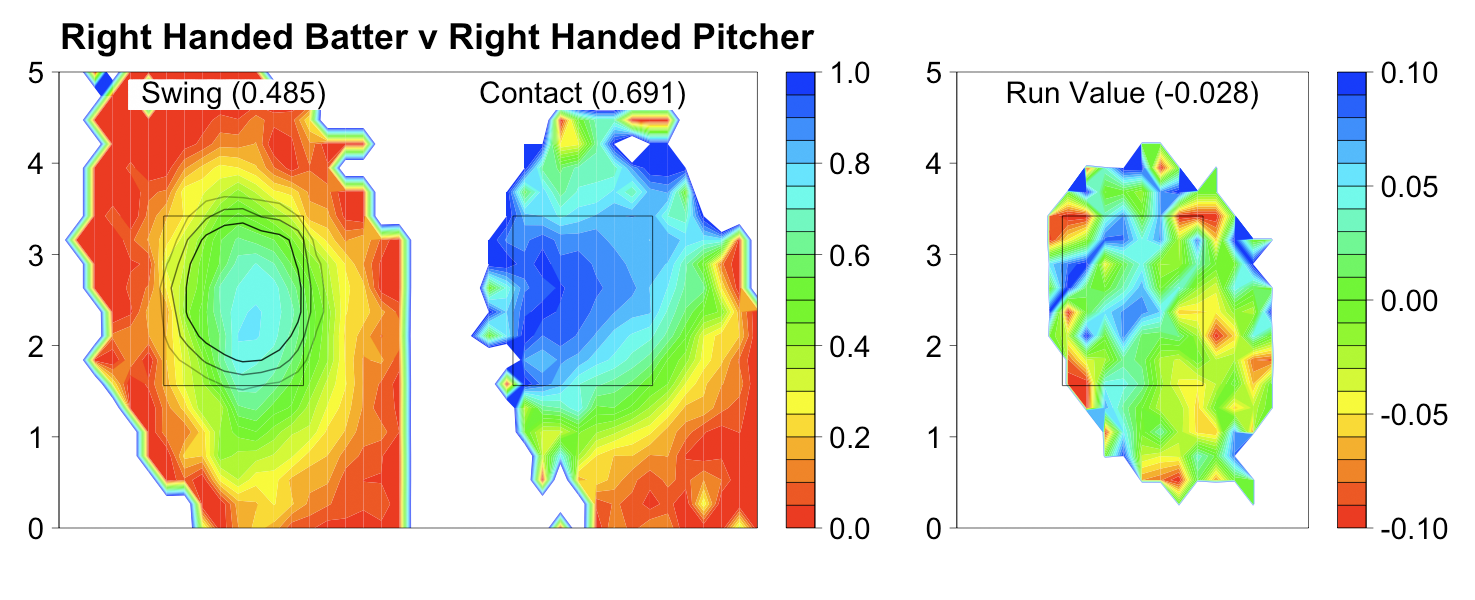

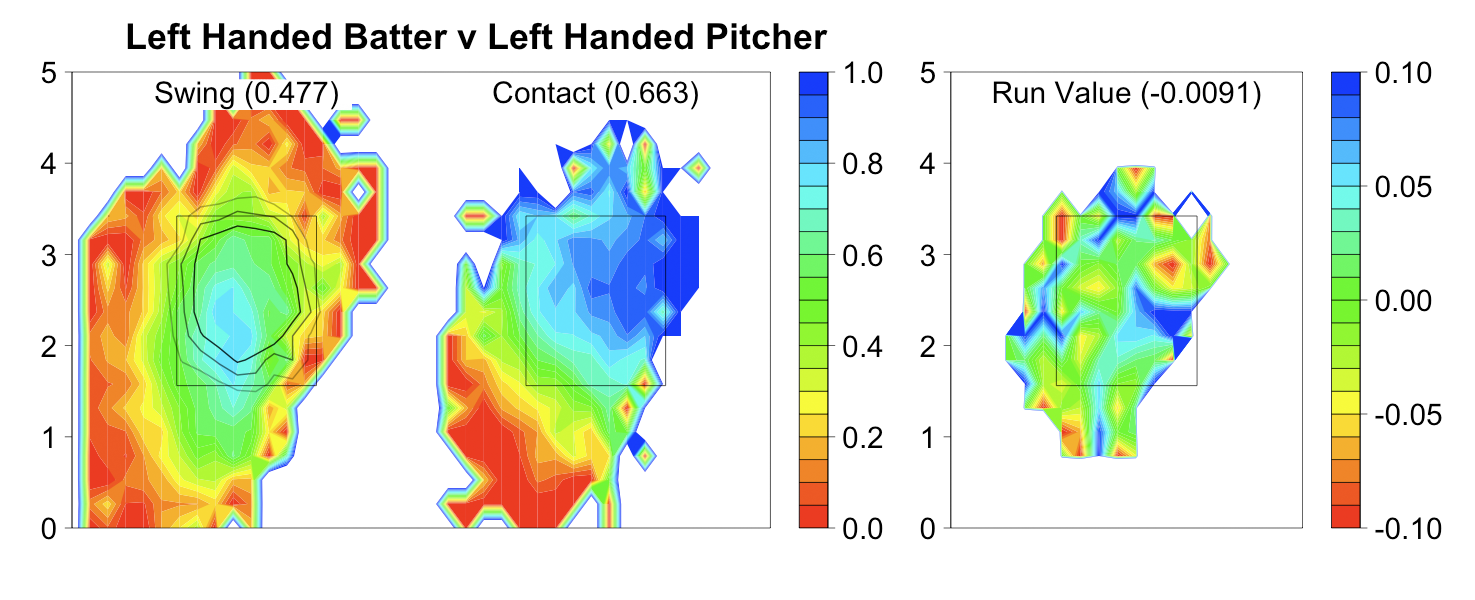

Below I present a series of three images for each handedness combination that show how the outcomes of these four events vary by location for fastballs. Reading left to right:

At the top of each image is the average value over all locations.

- The first image addresses events 1 and 2. The heat map is the swing percentage by location to address 1. On top of that are three contour lines where 75%, 50% and 25% of taken pitches were called strikes to address 2. So if a batter took a pitch inside the smallest circle it was called a strike over 75% of the time. If he took a pitch in doughnut between the smallest and middle circles it was called a strike between 75% and 50% of the time, and so on.

- The second image addresses 3 showing the contact percentage of pitches swung at.

- The final image addresses 4 showing the run value of a contacted pitch (including foul balls).

Since there are fewer curveballs, changeups and sliders than fastballs I smoothed and regressed the data more to make the images below. Thus they are not as finely resolved as the fastball images, but, I think, still convey the patterns well.

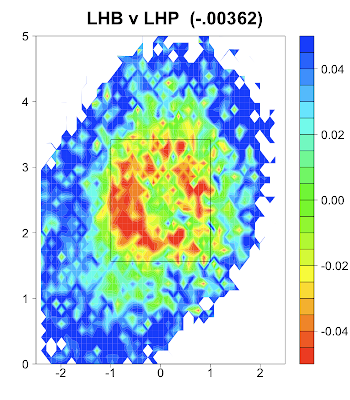

For each pitch I first present the original run value map. Recall the number at the top of each image is the percentage of time that pitch type is thrown in those at-bats.

Curveballs are thrown roughly equally in the different handedness combinations and have a large area of negative to zero run valued pitches below the strike zone.

Batters swing less at curveballs than fastballs, and the swing map is much less coincident with the strike zone for curveballs than fastballs. So batters are taking more curveballs for strikes and swinging at more curveballs out of the zone compared to fastballs. In addition, batters whiff more against curveballs than fastballs. But when they do make contact the run value is positive compared to negative run-valued contact versus fastballs.

Batters tend to swing more at curveballs down and slightly away, but make contact at a higher rate and better contact at curveballs up and in. Most likely this is a result of the down and away break of curveballs. Pitches that do break (or break a lot) end up down and away, and batters miss them or make poor contact. Pitches that don't break (or not enough) end up up and in, and batters rarely miss and make good contact.

Another interesting aspect of these images is how the strike zone is called for curveballs. The top, bottom and away edges are called in the same manner as fastballs are to RHBs, but the inside edge seems different. Recall that fastballs were called correctly along the inside edge, but curveballs are called considerable away (the 25% strike contour is inside the rule book edge). So umpires are calling inside fastballs strikes against RHBs, but not inside curveballs. I am not sure if this is a statistically significant difference, but I will look at that in a future post.

As expected RHBs make more and better contact against curveballs from LHPs than curveballs from RHPs. The orientation of the contact percentage gradient has shifted and is now high up and away to low down and in. This is a result of LHPs' curveballs breaking in to RHBs.

The swing percentage and contact rates are similar to RHBvLHP, but the run value of contacted pitch is, strangely, much lower. The orientation of the contact percentage gradient is the same as the one we saw in RHBvRHP.

Like for fastballs lefties facing lefties have the lowest contact rate by a large margin. But surprisingly the run value of contacted pitches is highest here, which was not the case for fastballs.

The orientation of the contact percentage gradient here looks like that seen in RHBvLHP not like the one seen in LHBvRHP. With fastballs the contact percentage and run value location patterns were determine by the hitters (RHBvRHP was more similar to RHBvLHP than to LHBvRHP) but with curveballs it is the pitchers handedness that determines the pattern (RHBvRHP is more similar to LHBvRHP than to RHBvLHP). It seems that the break of the pitch (determined by the handedness of the pitcher) is more important in determining these patterns than the inside/outside preference of the batter, which drove the fastball patterns.

Now we turn our attention to changeups. Here are the overall run value maps.

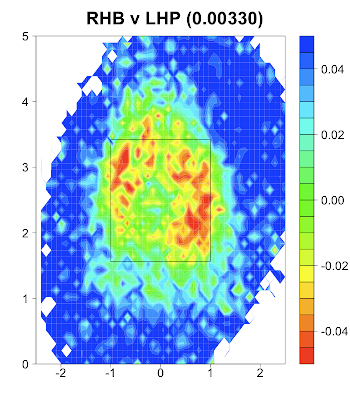

Changeups are thrown mostly in at-bats when the pitcher and batter have opposite handedness. So I will only present and comment on those images. But you can see the rightie/rightie one here and leftie/leftie one here.

Batters swing at changeups more than either fastballs or curveballs, and the swing percentage map is more coincident with the strike zone contours for changeups than for fastballs and curveballs. Meaning batters take fewer changeups for strikes and swing at fewer changeups out of the zone than for the previous pitch types. The highest swing percentage is slightly away and down, rather than up and in for fastballs.

Although batters swing at a lot of changeups and swing at the right pitches (in terms of the strike zone), they whiff on changeups at a relatively high rate. The highest contact rate and run value of contact are both up and in. Contacted pitches have a very slightly negative run value.

The strike zone to RHBs is called away on both the inside and outside edges and high on both the bottom and top edges. To lefties it is called away just on the outside edge and high just on the bottom edge. Again I am not sure these are statistically significant differences.

Finally, looking at sliders, here are the overall run value maps.

Sliders are thrown mostly in at-bats when the pitcher and batter have same handedness. So I will only present and comment on those images. But you can see the other ones here and here.

In same handed at-bats sliders are just nasty pitches. Batters swing at sliders slightly more often than fastballs (less than changeups and more than curves). But they are swinging at the wrong pitches, as the swing percentage map is considerably off from the strike zone (almost as bad as with curveballs). The whiff rate on sliders is enormous, considerably higher than any other pitch type. There is only a small part of the zone middle-in with a contact rate of over 85%. And then, even when batters make contact, the result has a negative run value.

.

Wrapping Up

We are now in a position to make some broad statements about what make the different pitch types successful.- Fastballs: With the exception of those directly above the strike zone, batters tend to swing at fastballs in the zone and take those out. They also whiff on fastballs at the lowest rate of any pitch. But contacted fastballs have very negative run values, the lowest of all pitches.

- Curveballs: Batters routinely take curveballs in the strike zone and swing at a high rate at curveballs below the strike zone. They whiff at a moderate rate. But when they make contact the run value is positive and higher than for all other pitches.

- Changeups: Batters tend to swing at changeups in the zone and take those out of the zone. But batters whiff against changeups at a moderate rate and contacted changeups have slightly negative run values.

- Sliders seem to have the best aspects of each pitch: the swing rate map is only slightly more coincident with the strike zone than that for curveballs, the whiff rate is higher than any other pitch, and contacted sliders have a negative run value (although not as low as contacted fastballs).

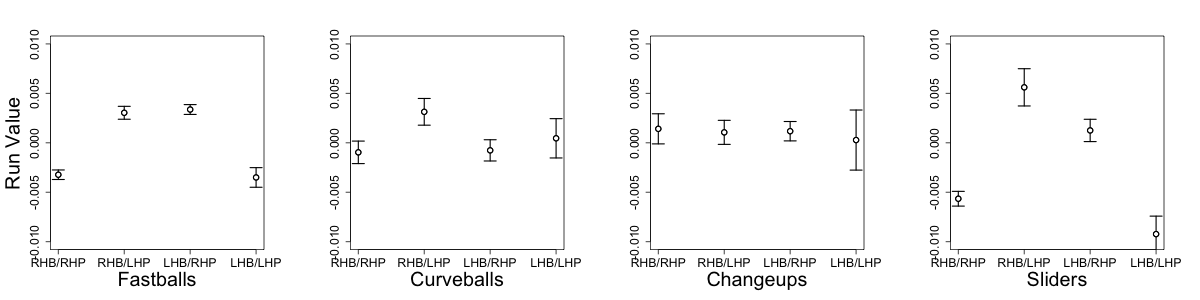

Below I present the overall run value per pitch separated by pitch type in a chart and figure. In the figure I indicate the standard errors.

Run value per pitch +------------+------------+------------+------------+------------+ | B/P hand | Fastballs | Curveballs | Changeups | Sliders | +------------+------------+------------+------------+------------+ | RHB/RHP | -0.0032 | -0.0009 | 0.0014 | -0.0057 | | RHB/LHP | 0.0030 | 0.0031 | 0.0011 | 0.0056 | | LHB/RHP | 0.0034 | -0.0008 | 0.0012 | 0.0013 | | LHB/LHP | -0.0035 | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | -0.0092 | +------------+------------+------------+------------+------------+

Fastballs and sliders show a statistically significant platoon split: there is a significantly lower run value outcome when the pitcher and batter have same handedness than when they have different. This makes sense with usage patterns for sliders, which are pitched more in at-bats when the batter and pitcher have the same handedness. You can also see here just how nasty sliders are to same handed batters, significantly lower than any other pitch.

Curveballs are interesting, there is no significant platoon split and there is a trend (although not significant) for curveballs from LHPs to have higher run value outcomes than curveballs from RHPs. This is strange as lefties throw curveballs more often than righties.

Changeups show no statistically significant platoon split. Which, again, is in line with what we expect based on their usage pattern. They are mostly thrown in opposite handed at-bats when fastballs or sliders would have a relatively higher run value.

This analysis has some serious limitations. I am using the MLB pitch classifications, which are far from perfect. There has been some work on developing better classification algorithms and I hope to incorporate one such algorithm in my future analysis. The pitches in this analysis are averaged over all pitch speeds and breaks, which is a major limitation. Just recently Dan Turkenkopf looked at how pitch speed impacted at-bat outcomes, and it would be interesting to see how pitch speed affects at-bat outcomes for each pitch type separately. Finally I average over all pitch counts. My next post will begin to address this last concern.

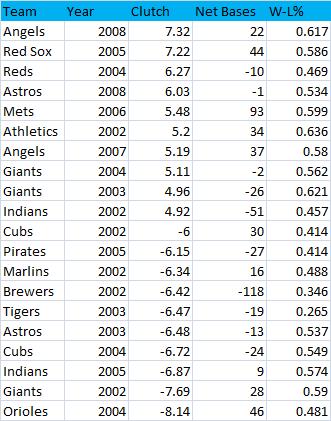

| Behind the Scoreboard | March 28, 2009 |

Opening day is right around the corner and soon your favorite team will be taking the diamond for its very first game. Hope springs eternal and the beauty of opening day is that every team starts at 0-0. As the season wears on, the games either become more or less meaningful depending on the standings. As a Cubs fan growing up in the 80's and 90's, I remember many a year when opening day was the most meaningful game of the year, with the rest of the season a slow march into irrelevance. In a lucky few years, the games took on more importance as the year progressed as the Cubs fought for contention. It's easy to tell which games are big and which games are meaningless, but this article attempts to put a quantitative number on the relative meaning of each game of the season.

Tom Tango's Leverage Index is a great tool for measuring the impact of a particular in-game situation. A Leverage Index of greater than 1.0 indicates the at-bat is more meaningful than an average play, and an LI of less than 1.0 indicates the at-bat is less meaningful, with LI's ranging from nearly 0 up to more than 5.

Taking this to the next level, we can create the same type of metric, except instead of producing it at a game level, we can produce it at a season level, with a value of 1.0 indicating an average regular season game's impact on a team's chances of winning the World Series. LI's larger than 1.0 will indicate the game has additional meaning, and LI's less than 1.0 indicate the game is less meaningful than an average regular season game. Dave Studeman touched on this subject at Hardball Times, but his index and mine, which I'll call "Championship Leverage Index" give quite different results.

Each team's Champ LI for a particular game is calculated by first getting the current probability of winning the World Series. Then we calculate this probability again, this time assuming that the team wins the game. The difference between the two is then found and this difference is the potential impact of the game. Tango's regular Leverage Index has to deal with multiple potential events, and thus has to calculate the standard deviation of the impact of winning depending on several outcomes, however in this case, because there are only two potential events in a game (win or loss), taking the difference in probability between the pre-game and post-game is sufficient.

For instance, in 2008, after 81 games, the Cubs probability of winning the World Series was 10.22% (81.8% to make the playoffs). A win in the 82nd game would up the probability of winning to 10.54% (84.3% to make the playoffs). This difference of 0.32% is the basis of the calculation of Champ LI. The difference is then indexed to the increase championship win probability of an average regular season game.

This average game, is also, not coincidentally, the same as opening day. Because nobody knows what the rest of the season will hold, the opening day game is, by definition, the average regular season game - depending on what happens sometimes it will be much less meaningful than other games, and sometimes much more. This increase in championship probability due to winning this average game is 0.28% (the increase in probability of making the playoffs is 2.25%). Using the example from above, 0.32/0.28 gives a Champ LI of 1.14, meaning the 82nd game (played with a 49-32 record and a four game lead over the Cardinals) was slightly more meaningful to the Cubs championship hopes than the average regular season game.

As you can imagine, the work that goes into this requires a lot of simulation. With simulations come assumptions, and here I assumed that all teams were of equal strength. This assumption is certainly not true, but it's acceptable because actual team strength is largely unknown, especially early in the season, and there is a nice symmetry to placing teams on equal footing. This is analogous to Tango's leverage index assuming opposing teams are of equal strength within an individual game. My current simulation also does not take into account the schedule of the teams, though that would be possible, changing the results very slightly.

Below are a few graphs to illustrate the Championship Leverage Index. First, are simply three graphs of each NL team's chance of making the playoffs in 2008 (to get the probability of winning the World Series, simply divide by 8).

Now let's look at the same graphs for each team's Champ LI. How much do the standings affect the importance of each game? As I mentioned before, each of the teams start opening day with an LI of 1.0.

To illustrate the Championship Leverage Index, let's focus in on the NL Central, which has a variety of teams that illustrate various scenarios nicely.

There are several interesting things to point out. As you'd expect, right off the bat, the teams that start poorly see their Champ LI decrease, while teams that do well see their games grow in importance. By late season, those teams that were out of the race, Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, had a Champ LI of essentially zero.

Similarly, the Champ LI also decreases dramatically when a team becomes too far ahead. After the Cubs 100th game, with a 1 game division lead and a two-game lead in the wild card, the Cubs games had a Champ LI of 1.70. But after they went on a tear and built up a 5 game lead three weeks later, their games' importance dropped dramatically, with the Cubs' Champ LI reduced to only 0.50. Because the playoffs seemed so likely, their games took on less importance. A few weeks later, coasting with a large lead, their Champ LI was reduced to essentially zero because the playoffs were assured.

We also see that the Champ LI of teams who remain in contention (but not too far ahead), grows as the season goes on. Furthermore, as long as a team is in contention, the game's meaning doesn't change much whether the team's prospects for the playoffs are on the high side or the low side. By the 125th game, the Cardinals and Brewers were both in contention, but had vastly different probabilities for the postseason (Brewers at 65% and the Cardinals at about 30%), however their Champ LI was about the same at around 2.0.

Another finding is, not surprisingly, all things being equal, late season games mean more. Eleven games into the season the Astros were struggling at 3-8, their playoff probability had dropped to 11%, and their Champ LI was down to 0.65, far less than an average game. However, fast forward to game #147 and the Astros, three games out of the wild card, had a playoff probability that was also about 11%. However, now the Champ LI was at 1.67, far more than an average game and certainly far more than their mid-April games when they had the same probability of making the playoffs. All things being equal, September games mean more than April games.

Furthermore, as the season draws to a close, if a team is still fighting for a playoff spot, their Champ LI grows exponentially. The Brewers' Champ LI was so high by the last games of the season (when they were fighting for a wild card spot with the Mets and Phillies), that their Champ LI is off the chart. By the last game of the season, which they went into tied with New York, their Champ LI was 11.1, meaning that the final game was 11 times more important than the average game (this is the maximum Champ LI for a regular season game, unless Milwaukee and New York had been playing each other, in which case the Champ LI would have doubled to 22.2).

Of course, the Champ LI applies in the postseason as well. You can see from the following chart below, the Championship Leverage Index of each possible postseason game, depending on the status of the series.

As you can see, every postseason game takes on vastly more importance than an average regular season game. The maximum Champ LI is of course, the 7th game of the World Series, with the game taking on 178 times as much meaning as an average regular season game.

Like Tango's individual game Leverage Index, the Championship Leverage Index doesn't exactly tell you anything new, but just quantifies a game's importance into a useful number. It can be useful in analyzing players' performance in "big games" as well as looking at things like attendance or TV ratings. It's also fun just to realize in quantitative terms exactly how much each game matters.

Another handy feature is that to figure out the importance of an individual at-bat within an individual game, you can simply multiply Tango's Leverage Index with the Championship Leverage Index. For instance, can you name the most important at-bat of the season last year?

It was Game 7 of the ALCS (Champ LI of 88.9) when JD Drew came to bat with the bases loaded, two outs, in the bottom of the 8th inning of a 3-1 game (game Leverage Index of 5.19). The total Championship Leverage Index of the at-bat is 461.4 (5.19 x 88.9), meaning that the at-bat was 461.4 times more important than an average regular season at-bat.

As Sox fans recall, Drew struck out, ending the inning. In one at-bat as big as some players entire seasons, he blew it. So what proportion of a championship did Drew lose by striking out? For that you'll have to wait until next week, when I introduce Championship Leverage Index's sister stat, Championship Win Probability Added.

| Change-Up | March 27, 2009 |

I am going to take a stab, FJM style, at tackling what really is the quintessential Jon Heyman piece. It combines two elements that are featured in so much of his work; his disdain for (some) numbers and his continued, shameless PR work for Scott Boras Corp.

You might recall his commentary from the MLB Network studios the day the Hall of Fame results were announced. From Rich Lederer's January 13 piece.

"I never thought [Bert Blyleven] was a Hall of Famer when he was playing, and I saw him play his entire career.""[His popularity] is based on a lot of younger people on the Internet who never saw him play."

"It's not about stats...it's about impact."

You might also recall Rich's trip through the Heyman/SBC archives.

While Boras is no fool, Heyman is a tool for the Scott Boras Corporation. Boras knows how to game the system to get the best deals for his clients and will gladly use Heyman as long as the latter plays along or until the market realizes what is going on. As it stands now, it's almost as if Heyman, who is no stranger to the Boras suites during the winter meetings, is on the SBC payroll.

Anyway, Heyman is back today with a scatterbrained defense of Curt Schilling's Hall case, as well as more gratuitous Manny Ramirez praise.

Let's have a look (Heyman's writing in bold).

---------

Curt Schilling has to be in the Hall of Fame.

No, he doesn’t. If you think he belongs in the Hall of Fame, then that’s a different matter. Just make your case.

I write that without any hesitation, reservation or research. I don't need to look at his stats. I know what he's done.

Oh, never mind. You’re not interested in making the case. Because if you were, you would need to look at his stats. It would allow you to assess how he performed throughout his career.

The Hall of Fame should be about impact, not statistics. Numbers are nice, but they don't necessarily make the player.

"Impact, not statistics." And how exactly do you suggest we measure “impact”?

For instance, in 2001, Curt Schilling threw over 256 innings, struck out 293 batters, walked just 39 and had a 2.98 ERA. He threw another 48 innings in the post-season, giving up six earned runs, striking out 56 and walking six.

Some might say that those statistics offer a good indication of Schilling’s “impact” for that season.

Some Hall of Fame cases are being built on a pile of numbers now, and I can see how in rare cases a player's career can be re-evaluated by dissecting the latest data.

Ooooh. A not-so thinly veiled reference aimed at Rich over his Blyleven case. Well played, Heyman. Here’s Rich “dissecting the latest data" as it relates to Blyleven:

5th all time in strikeouts, 8th all time in shutouts, 19th in wins.

Pretty cutting edge stuff.

But in general, I think that's a funny way to get into Cooperstown. Conversely, Schilling is maybe the perfect example of a pitcher who had great impact but whose career regular-year numbers are merely excellent but not among the all-time best.

Yes, evaluating a player’s performance sure is a peculiar thing.

The Hall of Fame should be for players who did great things, staged big moments and affected things the way Schilling did.

Stats measure all of these things.

Like him or hate (and I can't say I fall into the former category there, as I consider him a cyber and in-person annoyance), Schilling had a tremendous impact on most games he pitched, and on the game itself. He was a star who pitched his team into four World Series, and to three titles. In 2001 and 2004 in particular, it was his pitching that made the difference.

1) It’s not in any way relevant to Schilling’s Hall case how you feel about him, Jon. No need for the caveats.

2) Most pitchers impact games they pitch. Mark Hendrickson impacts games he pitches. Stats help to measure what kind of impact.

I ran into Schilling's former Phillies teammate Dave Hollins the day Schilling announced his retirement, and after one of us joked about whether Schilling would follow through on his announcement or stage some dramatic comeback, Hollins offered the long-held view of Schilling, but in a nicer way. "You love to have him on your side every fifth day,'' Hollins said.

Former Phillies GM Ed Wade expressed a variation of that statement (only said much harsher) many years ago. It went something along the lines of, "He was a horse once every five days and a horse's ass the other four days.''

More character references. Terrific.

Although I never spent four consecutive days with Schilling, I don't doubt that. He always came off as a guy who thought he was an expert in everything simply because he had more pitching talent than just about anyone else. He still blows hard on his 38Pitches, a Web site I religiously avoid.

I don't particularly like Curt Schilling. I generally don't agree with his politics, I do think he is something of a grand-stander and I think he is perpetually conscious of his image in a way that puts me off. But he's a thoughtful guy, and I appreciate that a Big League player takes the time to write as much as does and directly engage fans of the game. Heyman thinks he's a blowhard because he is bypassing him and talking directly to us. He is threatened.

But anyway, here’s something I encourage everyone to do. Go read some of 38Pitches. Then read some of Heyman’s work. You can then judge for yourself who’s the blowhard.

Anyway, Schilling still gets credit for that fifth day, not demerits for the other four. Schilling was often great on that fifth day, and he was almost always great when it mattered most.

It takes a big man to look past those four days he never once had to spend with Schilling and evaluate him on his pitching. Or his impact. Or his moments...or however it is Jon Heyman evaluates baseball players.

There are people who believe that he played the famed "bloody sock'' game for all it was worth, that he purposely made it look good, or at least did nothing to stem the flow of blood. I wouldn't put much past Schilling, but I am convinced that he was hurt, and that he was bleeding, and that he should get credit for pitching heroically that day, for beating the Yankees and the jinx, and for helping the Red Sox win the World Series for the first time in 86 years

The bloody sock has nothing to do with how Curt Schilling performed.

He called a championship for Boston -- saying that was his intention the moment the Diamondbacks traded him there -- then he delivered. That's almost Namath-like. Joe Namath's career football numbers aren't so perfect, either, and nobody doubted his Hall of Fame qualifications.

Round and round we go. Joe Namath was probably not a Canton-worthy performer but he guaranteed a victory while playing in America's biggest media market so he became a big star. The media made him that. When it came time to vote him for the Hall, many of the same media members, Hall voters, referenced the guarantee in building his case.

So here you have Heyman citing a football player's Super Bowl guarantee, famous only because the media made it such, in helping to build his case for Schilling. It's all very, very stupid.

Championships are what it's all about…

I don’t know. Ty Cobb, Barry Bonds, Ted Williams and Willie McCovey were all pretty good.

…and Schilling played as great a role in winning championships as just about any player of his generation except Mariano Rivera.

Manny Ramirez, David Ortiz, Derek Jeter, Bernie Williams, Andy Pettitte, David Cone and Roberto Alomar might disagree.

That Schilling won "only'' 216 games shouldn't be counted against him. That he had "only'' maybe seven or eight great seasons shouldn't either. If it's about numbers, it shouldn't only be about total numbers. He had three 300-strikeout seasons, three 20-win seasons. He struck 3,116 batters while only walking 711.

He had all-time stuff. And as much as I hate to admit this, he had all-time heart. He was 10-2 with a 2.23 ERA in the postseason. He and Randy Johnson were the two biggest keys to the Diamondbacks winning the thrilling 2001 World Series, and he and Manny Ramirez were the keys to the Red Sox winning the historic 2004 Series.

This is my favorite part about these columns - the part where the writer rails against statistics, only to then cite statistics just paragraphs later.

So anyway, now we’re talking statistics. Which is it, Jon?

It's safe to say Schilling is about the last person I'd want to spend any appreciable time with. But if I had a game on the line I had to win, and if Sandy Koufax wasn't available that day, I'd give John Smoltz or Schilling the ball.

Oh, Schilling is the last person you’d want to spend time with? I think I know who the first is…might it be Manny Ramirez’s agent?

There is plenty of offensive firepower in the San Francisco Giants clubhouse. Or there was on the day I visited. Willie Mays was sitting at a table in the clubhouse, Willie McCovey was resting in the dugout, and Will Clark was chatting with current players. The Giants' starting pitching looks so good, it's truly a shame they don't have at least one active player anywhere near as good as any of those guys in their prime.

Among active players, Manny Ramirez would have made a nice addition to the Giants. He could have replicated the years of Barry Bonds, with comparable productivity, less controversy and more good cheer.

No, Manny Ramirez could not have replicated the years of Barry Bonds. And good grief, Jon. Please give us a break. With Stephen Strasburg looming, we don't even get to wait until next off-season for you to start shilling for Boras again.

Let us enjoy the start of the baseball season in peace.

| Designated Hitter | March 26, 2009 |

Back in 1988, in an attempt to make a little extra money during graduate school at UC Berkeley, I tried out to be an umpire for intramural softball. We were given a brief instruction on what to do and a mock game was set up as a tryout.

I was working first base and there was a grounder hit to the second baseman. I tried to remember where I was supposed to stand (about 15 feet behind the bag at a 45 degree angle to either side depending upon whether or not the throw was coming from the left or right side of the infield). The ball was hit... somewhere... and I ran to stand in position. Except I stood near the pitcher in the middle of the play. And then I tripped over my own feet and fell over. I found other part-time employment.

Bruce Weber, a New York Times reporter, had a bit more success when he visited the Jim Evans Umpire School back in 2005 and he ended up writing an interesting book about the lives of umpires, both minor and major leaguers, in his As They See 'Em: A Fan's Travels in the Land of Umpires (Simon and Schuster, $26).

Bruce Weber, a New York Times reporter, had a bit more success when he visited the Jim Evans Umpire School back in 2005 and he ended up writing an interesting book about the lives of umpires, both minor and major leaguers, in his As They See 'Em: A Fan's Travels in the Land of Umpires (Simon and Schuster, $26).

Starting with the bizarre world of umpire school (one student's employer told him "they have a school for that?"), where prospective umpires are put through drill after drill to get them to see a game as an umpire does, instead of as a fan. Weber also has some interesting stories about how umpires are drilled in how to argue with managers and players, and even more importantly, how to take off their mask without having their cap fall off. The latter is extremely important it turns out, although if more umpires start using the hockey style masks, that arcane art may disappear.

Like players, umpires are taught where to position themselves and how to anticipate plays. The most common time you will see an umpire out of position is when a player does something completely unexpected, such as throwing to the wrong base. After all, if the player shouldn't throw to a certain place, why should they be in position to cover a situation caused by a player's mental error.

As Weber points out, umpires are part of baseball that has no constituency that likes it. Players and managers don't like umpires, and umpires like to call players "rats." Front offices don't like umpires. Even the Commissioner's Office, which employs umpires, really doesn't like them. Former Commissioner Fay Vincent says that teams view umpires like they were bases, just pieces of equipment that you have to have to play the game.

One of the hardest things Weber faced in writing his book was getting people to talk to him. Players and managers generally didn't want to speak to him because they feared payback from umpires. Even Earl Weaver, long out of the game, wouldn't speak to Weber about umpires. Umpires didn't want to speak too much out of turn because they feared for their job security.

Umpires who graduate at the top of their classes at one of the two umpire schools (Harry Wendlestedt operates the other one), are given jobs in Rookie or Short-season A leagues as parts of two-man crews who drive hundreds of miles between cities and stay in motels that often appear as if they have hourly rates. MLB views minor league umpiring as "seasonal work" so the pay is low, sometimes around $800 per month. It's a job you have to love somewhat because most people could make better wages at McDonald's.

For the privileged few who make it to the majors (there are 68 full-time MLB umpires), the job becomes even more tense. Every call is scrutinized and there is nothing positive that an umpire can do. They can only screw up.

Since an MLB umpire's job is so coveted, Weber could only get a few umpires to speak to him on the record and even some were not entirely forthcoming. The disastrous mass resignation plan of 1999 has left deep wounds among the corps of umpires. Interestingly, Weber points out that even though umpires were no longer separated by league at the time, the battle lines in that dispute split along AL-NL lines, with the AL umpires (who long felt that they were below the NL in the pecking order) taking the opportunity to assert leadership in a new union.

I found the best parts of the book when Weber goes into some detail about the mechanics of umpiring. It's one part of baseball that few people seem to care about, unless they think an umpire screwed up. Then people are experts on the matter.

For example, when there is a bunt play going on and the defense puts on "the wheel" play, watch the umpires. They don't move. They have to watch the bases. But if there is a ball hit down the left- or rightfield lines, the umpires will wheel around, while the infielders will generally stay by their bases to make a play on a runner or the batter-runner. (If you want to be an umpire, learn to say "batter-runner," "ball-strike indicator," and don't let anyone call you "Blue.") Umpires also have responsibilities to make sure that all the runners touch their bases and it's a subtle skill that they pick up over time.

Weber also gets umpires to explain how pitchers like Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine get seemingly wider strike zones than other pitchers. Briefly, it's because those pitchers have such good control that they can keep placing the ball further and further on the corner of the strike zone. And then they are able to work inside and outside the edge until the outside edge of the strike zone gets wider because of the umpire's perception of where the pitches go. Maddux and Glavine in a sense have earned bigger strike zones because of their skill, and not just because of their reputation.

One thing that did surprise me is how open umpires were to technological improvements in the game. Replay review of home runs was welcomed because the umpires know how difficult some parks were for making those calls. It's likely that in 2009, umpires will err on the side of calling a ball in play rather than a home run because it is simpler to remedy that call with replay rather than the other way around.

The final chapter of the book includes interviews with umpires who have made some of the most controversial calls in recent history: Larry Barnett (who didn't call interference on Ed Armbrister in the 1975 World Series, despite Carlton Fisk's protestations), Doug Eddings (of the 2005 ALCS call involving A.J. Pierzynski and Josh Paul and the dropped third strike), Richie Garcia (of Jeffrey Maier fame), Tim McClelland (who was the umpire for the George Brett Pine Tar Game and The Did Matt Holliday Touch The Plate Game), and Don Denkinger (1985 World Series Game 6, bottom of the 9th).

Each umpire gets a chance to explain what they did and didn't see or what they did or didn't do. Denkinger freely admits blowing the call on Jorge Orta, but explains how it came about. But that will likely not satisfy Cardinals fans. Some of them still want blood 24 years after the fact.

Weber wants fans to have a greater appreciation for the work that umpires do. The umpires are far from a perfect lot. They are profane. They are sexist (the few female umpires who have been in the minors were treated horribly). They aren't there to make the fans or players happy. They are at games to keep them under control. It's a job that not many people have the ability or temperament for. But those that do it, do care about doing their jobs well. Nevertheless, I predict plenty more complaining about umpires this year from just about everybody. It's one of baseball's constants.

From the benches, bleak with people, there went up a muffled roar,

Like the beating of the storm waves on a worn and distant shore.

"Kill him! Kill the umpire!" shouted someone in the stands,

And it's likely they'd have killed him had not Casey raised his hand.

- From "Casey at the Bat" by Ernest Lawrence Thayer, 1888

Bob Timmermann, formerly of The Griddle, is a senior librarian for the Los Angeles Public Library and runs One Through Forty-Two or Forty-Three.

| Designated Hitter | March 25, 2009 |

[Editor's note: John Brattain, a writer for The Hardball Times, Baseball Digest Daily, and his own blog Ground Rule Trouble, and a sincere friend of Baseball Analysts, passed away on Monday due to complications from heart surgery. John, who is survived by his wife Kelly and two daughters, was 43 years old. Known as "The Bones McCoy of THT" at the Baseball Think Factory, his signature line was "Best Regards, John." In sympathy and as a tribute to John and his family, we present his guest column — a terrific piece about Robert Lee "Indian Bob" Johnson — from December 22, 2005. Best Regards, John. - Your Pals at Baseball Analysts.]

One of the great oddities in baseball is how we perceive players. If a player does one or two things spectacularly well, he ultimately ends up being better regarded than players who do a lot of things well. Of recent vintage was 1998 and 1999 when home run behemoths Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa got all the ink over players like Barry Bonds and Ken Griffey Jr. Earlier in the decade in Canada RBI man Joe Carter had a higher profile than Larry Walker. Or, if you wish to go back to the 1970's and 1980's, you'll find more casual fans have heard of Dave Kingman over Dwight Evans.

For that matter, don't you find it odd that Tim Salmon never went to an All-Star Game? Not one.

Bill James said in his book Whatever Happened To The Hall of Fame--The Politics Of Glory that players who do one or two things well tend to be overrated while those who do a lot of things well tend to be underrated.

Today we're going to talk about an historically underrated player. He didn't have one ability that defined him but didn't have a single hole in his game: he could hit, hit with power, run, field and throw. Baseball-Reference has tests that involve Black Ink and Gray Ink. Black Ink describes how often a player led the league in some statistical category; Gray Ink describes how many times he finished top ten in the league. This player has two points of black ink but 161 points of gray ink.

In other words, he was never the best, but consistently among the best.

We're talking about Robert Lee "Indian Bob" Johnson.

Johnson was born in Oklahoma in 1906, and his family soon moved to Tacoma, Washington. He left home in 1922 at age 15 and began his baseball career with the Los Angeles Fire Department team. Because Johnson was part Cherokee, he was subjected to the nickname "Indian Bob," just as other players of Native American ancestry had similar epithets foisted upon them in this era.

Johnson was soon playing semi-professional ball. When his brother, Roy Johnson, became a professional, he felt buoyed. He said, "When Roy became a regular with San Francisco in 1927 I knew I could make the grade in fast company. I had played ball with Roy and felt I was as good as he was."

However, Johnson failed trials with San Francisco, Hollywood, and Los Angeles. He did not play professionally until Wichita of the Western League signed him in 1929. Johnson played in 145 games at two levels and batted .262 with 21 HR while slugging .503. After again hitting 21 HR (in just over 500 AB) the following season in Portland, he went to spring training with the Philadelphia A's but didn't make the roster due to his inability to hit the curveball. Over the next two seasons in the minors, Johnson batted a combined .334 with 51 HR while slugging .567 and showing both patience at the plate and a powerful throwing arm in the outfield.

Opportunity knocked in 1933 as Connie Mack sold off veteran Al Simmons to the White Sox leaving Johnson and Lou Finney to battle for the leftfield job in spring training. Johnson won the job and had an excellent freshman season at age 27...

AVG/ OBP/ SLG Runs 2B 3B HR RBI OPS RCAA .290/.387/.505 103 44 4 21 93 134 37

...and was generally considered the league's finest rookie.

Johnson would quickly prove that 1934 was no fluke. On June 16th, the A's and White Sox played a twin bill. After losing the opener 9-7, the A's come back to win game two 7-6. Johnson went 6-for-6 with two home runs (both off Whit Wyatt), a double, and three singles. Four days later, he hit his 20th round tripper of the season against the Browns giving him the league lead (he finish fourth). He also enjoyed a 26-game hitting streak. After two fine seasons, Johnson was beginning to get recognition as he was named the starting left fielder of the American League All Star team in 1935. Johnson also finished fourth in the loop in home runs for the third time in his first three seasons and enjoyed his first 100 run/100 RBI season (he had topped 100 runs in both 1933 and 1934).

Despite turning 30 in 1936, Johnson kept right on raking and showed a little extra speed on the base paths, hitting a career high 14 triples. In both 1936 and 1937, he ripped 25 HR driving in 100 runs despite not getting 500 AB in '37; of interest, on August 29 he again victimized the White Sox in a doubleheader as the A's set a new AL record in the opener of a twin bill by scoring 12 runs in the opening frame, six of which were driven in by Johnson. After four years in the majors, other aspects of Johnson were becoming known around the league. Johnson was a bit of a practical joker, and it was in 1937 when Yankees' HOF second baseman Tony Lazzeri pulled a prank on him, knowing he would probably appreciate the joke.

Lazzeri doctored a ball over the course of two weeks by pounding it with a bat, soaking it in soapy water, and rubbing it extensively with dirt and finally coating it with white shoe polish to make it look like new. Bill James described it as a ball that was "as dead as Abe Lincoln." It was so heavy and lifeless that it would plop down harmlessly once struck with a bat.

Lazzeri sprang his joke on September 29 long after the Yanks had clinched the pennant. During an inning in which Johnson was due to bat, he ran out to second base with the gag ball in his pocket. When Johnson stepped into the batter's box, he trotted out to the mound and switched balls with Yankee southpaw Kemp Wicker. Wicker grooved Lazzeri's "mushball" down the pipe and Johnson took a mighty cut and hit it on the screws. However, rather than hitting a prodigious moonshot, the ball plopped harmlessly foul behind the plate while a perplexed Johnson stood there wondering just what the hell happened while the other players and the crowd burst into laughter.

Johnson continued to get better as he aged as he put together his best two seasons at 32 and 33, topping 110 runs/RBI both years while batting at least .300/.400/.500. On June 12, 1938, Johnson was a one-man wrecking crew against the St. Louis Browns, hitting three bombs (and a single) and driving in all eight runs.

1938 and 1939

AVG/ OBP/ SLG Runs 2B 3B HR RBI OPS RCAA .325/.422/.553 229 57 18 53 127 146 95

Johnson was also developing the reputation of being an athletic fielder. He lead the AL in assists twice (in The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, the best outfield arm of the 1940's is said to be either Johnson or Dom DiMaggio and he was also 4th all-time in outfield assists per 1000 innings) and also filled in occasionally at second and third base (poorly it should be added). He was named to the AL All-Star team both years.

Johnson finally began to show the effects of age during his age 34 and 35 seasons and started to lose some bat speed. Connie Mack even felt the need to give his star slugger time off from covering the expansive left field pasture at Shibe Park, playing him 28 games at first base in 1941. He still had power and a sharp batting eye and remained a potent RBI man, topping 100 RBI in both 1940 and 1941--the latter his seventh straight season over the century mark.

Johnson's power started to wane in 1942 as he suffered through his worst season statistically to that point in time, failing to hit 20 HR or 90 RBI for the first time in his career. However, part of this was attributable to the fall of offense across the board due largely to players enlisting in the military for WWII. His OBP and SLG marks were still good for top 10 finishes in the Junior Circuit and good for fifth in MVP voting. After continually clashing with Mack over pay, the manager finally said goodbye, sending him to the Washington Senators for third sacker Bob Estalella and Jimmy Pofahl. Baseball Almanac notes that this was the only time in baseball history where a player who led his team in RBI for seven straight years was traded.

Johnson lasted one year with the Senators where age and huge Griffith Stadium all but neutered his power as he slugged a career low .400, and for the first and only time in his career he failed to hit at least 10 home runs (7). He was sold to the Boston Red Sox by Griffith who later regretted the move. The diluted war-time talent in the majors coupled with Fenway Park's hospitable climate for right-handed hitters allowed Johnson to finish out his major league career in style. In a season which either spoke highly of Johnson's ability at age 38 or spoke poorly of the level of war-time talent left in the majors by 1944--*cough* Browns win the pennant...Browns win the pennant *cough*--Johnson enjoyed his finest statistical season (including hitting for the cycle on July 6):

AVG/ OBP/ SLG Runs 2B 3B HR RBI OPS RCAA .324/.431/.528 106 40 8 17 106 174 61

Still, a lot of other fine players also played through the war years including HOFers Paul Waner, Chuck Klein, and Joe Medwick and didn't play as well as Johnson. Further, he was able to play 142 games in left field and enjoyed his first season on a team .500 or better since his rookie year as the Red Sox finished 77-77. For his efforts he was named to his seventh All Star team and finished 10th in MVP voting. As World War Two dragged on to 1945, Johnson was able to enjoy one last moment in the major league sun. He played 140 games in left field and provided the Red Sox with 82 runs created (AL left fielders averaged 67 RC in 1945), which earned him his eighth and final All Star nod. With the war over, Johnson pushing 40, and the return of Ted Williams, the Red Sox and Johnson parted company and he continued his career with the Milwaukee Brewers in the American Association.

Despite his advanced athletic age, Johnson managed to hit .270 with 13 HR and a .456 SLG in 94 games. He moved on to Seattle of the Pacific Coast League for the next two years, batting .292 with 35 doubles, 12 HR and a .441 SLG in 487 AB. Johnson, now 44, went home to play for and manage the Tacoma Tigers in the Western International League where he wielded a potent bat, hitting .326 with 13 doubles, five homers and a .463 SLG in 218 AB. He didn't play in 1950 but resurfaced briefly in Tijuana the following year at age 46. Johnson batted .217 in 21 games, then hung up his spikes for good.

So how do we measure Johnson's career? He probably missed being a Hall of Famer by a whisker. Johnson was hurt perceptually due to playing on second-division teams never reaching the World Series or even coming particularly close to one. He was also overshadowed by all-time great outfielders like Joe DiMaggio and Williams. Further, he finished his career during the second World War. Also working against him was his consistently high level of play; his OPS never going higher than 174 or dropping below 125 and always provided above-average offense for his position. He never had an eye-popping, jaw-dropping season that nets players MVP awards. He is also perceived by many to be the equivalent of the Phillies fine outfielder of the 1940's and 1950's, Del Ennis.

In short, he was invisible.

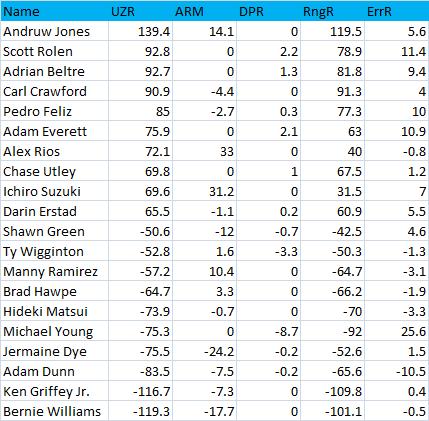

However, when we examine his record, he fits right in with four contemporary outfielders who are in the Hall of Fame and three of whom--like Johnson--finished their careers during WWII: Earl Averill, Klein, Medwick, and Paul Waner.

Player AVG OBP SLG Runs HR RBI OPS RCAA* Bob Johnson .296 .393 .506 1239 288 1283 138 413 Earl Averill .318 .395 .533 1224 238 1164 133 391 Chuck Klein .320 .379 .543 1168 300 1201 137 409 Paul Waner .333 .404 .473 1190 139 957 134 588** Joe Medwick .324 .362 .505 1198 205 1383 134 368 Del Ennis .284 .340 .472 985 288 1284 117 145

* Runs Created Above Average is a counting stat

**Waner's career length is the longest of the six players

As mentioned, a lot of folks dismiss Johnson's achievements because of a superficial statistical similarity to Del Ennis. I threw Ennis in here to show that he's not at all comparable to the above group. His HR/RBI totals are similar but he's last in AVG/OBP/SLG, runs, OPS and RCAA. The difference between Johnson and Ennis' respective levels are about the same as Rusty Greer (120 OPS /149 RCAA) and Chipper Jones (141 OPS /429 RCAA); nobody suggests that Greer and Jones are similar as hitters. In the chart above, we can see how close Johnson's level of play was to Hall of Fame quality. His eight All Star selections reflects the high regard contemporaries viewed Johnson. After Al Simmons was sold to the White Sox, Johnson all but became the Athletics offense. During his ten years with the A's, the team created 7612 runs. Johnson was responsible for 1162 (15.26%). The roster over that ten years were -420 RCAA while Johnson had 317 RCAA.

Although never topping statistical lists, Johnson was consistently among the leaders. From the period 1930-50, Johnson was tied for second in doubles (396), eighth in triples (95), third in home runs (288), third in runs (1239), second in RBI (1283), sixth in OBP (.393), sixth in SLG (.506), and fifth in OPS (.899). Here are the top ten finishers in RCAA (totals accumulated before 1930 and after 1950 are not counted):

1. Ted Williams 908 2. Joe DiMaggio 695 3. Babe Ruth 460 4. Bob Johnson 413 5. Charlie Keller 394 6. Earl Averill 356 7. Tommy Henrich 274 8. Jeff Heath 261 9. Al Simmons 250 10. Roy Cullenbine 215

Johnson's RCAA is 73rd all time. When you consider that, along with being a fine fielder with a terrific throwing arm, you begin to appreciate the complete package that was Robert Lee "Indian Bob" Johnson. Truly an All Star in the fullest sense of the word and an unappreciated talent. When you look back at some of the superb players to grace the diamond in the 1930's and 1940's, don't forget about the man that patrolled left field at Shibe Park for a decade.

John Brattain writes for The Hardball Times and his work has been featured at About.com, MLBtalk, Yankees.com, Replacement Level Yankee Weblog, TOTK.com, Bootleg Sports, and Baseball Prospectus.

[Additional reader comments and retorts at Baseball Primer.]

| Touching Bases | March 24, 2009 |

All home runs are not created equal. Over the course of a six-month season, things are bound to change. Players wear down or maybe some heat up. In the past, we've been able to find player trends by analyzing first-half and second-half splits or maybe even game logs. But now with new data sources, we can try to find out how or why players produce different outcomes over a season. Are they lucky? Do their skills improve? Do they fatigue?

Josh Kalk used pitch f/x data to show how pitchers fatigue during starts and he unveiled wear pattern charts for specific pitchers to show how some fatigue over the course of a season.

Another great new data source that has not received the same attention as pitch f/x is Hit Tracker. Developed by Greg Rybarczyk, Hit Tracker tracks every physical aspect of the home run. So how did the distance of home runs vary over the course of the 2008 season?

"True Distance" measures how far the ball actually traveled, or how far the ball would have traveled had it landed uninterrupted. I know, if only we could project how far Mickey Mantle’s and Ted Williams' legendary shots traveled. Well, Hit Tracker can. Here and here you go.

The chart seems to show that home run distances trend upward until early August and then fall slightly. It also appears that we can say with confidence that over the course of a week, the mean home run distance will be right around 390-400 feet. The first data points on the chart are a bit whacky, since the March average was 399 feet per home run, but then the first three days of April averaged 390-foot homers per day. Hence, the five-day rolling average is somehow much lower than the same month's average. But the main observation is that from April until July, there is a rather distinct increase in home run distance—around five feet per dinger. So what causes the change? Perhaps players need some time to get into their groove, or perhaps the environment becomes progressively more conducive to home runs. But how do we measure that? Did I mention that Hit Tracker also records the two most important components a batter can control? It captures where and exactly how hard the ball is hit. With the upcoming advent of hit f/x, we might get this data for all types of batted balls. The launch angle is measured in horizontal and vertical degrees from the point of contact three feet above home plate, while the speed off bat is measured in miles per hour. I chose to use the speed off bat as a measure for the player’s skill over time. I believe that a hitter's objective when he is at bat is to hit the ball as hard as possible. Here are the results:

Well, that appears to directly contradict what we saw in the first chart. Players seem to start off hot in the opening weeks of the season, but then by late May the average speed off bat flattens out at around 104 MPH until playoff time when there is a pretty decent rise. It would make sense that the select few who are able to hit homers in October do so with more power than the average hitter.

If it’s not the hitter who controls the change home runs, then it must be the hitter’s environment. Fortunately, Hit Tracker also records atmospheric effects such as temperature, wind, and altitude. Altitude should theoretically remain constant over time, as stadiums don't traditionally switch locations. But wind and temperature flow with the seasons. Since both factors can negatively impact the distance a ball travels, I plotted the absolute average impact as well as the actual average.

The impact due to temperature is defined as “the distance gained or lost due to the impact of the ambient temperature, in feet, as compared to a 'standard' temperature of 70 degrees." Temperature, along with the Speed Off Bat appear to largely explain the opening chart which showed the average true distance of home runs over the course of 2008. I’m not a physicist, but I figure a change in one mile per hour is equivalent to about 1.5 feet per second, and the average home run stays in the air around 3-5 seconds. So if the speed off bat decreases half a mile per hour in the early months, then the batter is responsible for about a three-foot decrease in distance. Yet the average true distance of home runs increases from about 395 in April to 398 feet in July. While the batter might cause at most a five-foot dip as the season progresses, the temperature appears to rise from a minimum average of -5 feet to a high of 5, which would explain the rise in distance. I’m also not a meteorologist, but the symmetry makes sense to me as the temperature rises in the spring, then peaks around the June 21 solstice, maintaining that point through the dog days of August, until the temperature declines going into the Fall classic. Not exactly shocking results.

Putting it all together with the standard distance, which controls for atmospheric effects and simply measures how far the ball would have been hit in neutral conditions:

Looks pretty even throughout the season, with the exception that distance possibly curls up at the start and end points. This could all be contributed to small sample size, but the fact that better players make the playoffs may have something to do with it, but do better players also start out hot? I'll be sure to keep note of it over the next few weeks.

Here's a chart of the three year's worth of data. Out of about 15,400 homers, Hit Tracker was missing data on less than 300 of them. The table should be read as the mean of each category, followed by standard deviation in parentheses.

Month Amount True Distance Speed Off Bat Wind Effect Temp Effect Standard Distance March 26 399.8 (25.3) 105.6 (5.7) 5.4 (17.5) -4.0 (2.4) 396.7 (33.5) April 2214 395.6 (24.7) 106.1 (5.2) 1.7 (13.2) -2.5 (4.3) 393.8 (27.1) May 2522 396.0 (25.3) 105.6 (5.2) 1.8 (11.7) -0.2 (3.7) 392.1 (26.2) June 2545 396.6 (25.5) 105.1 (4.9) 2.0 (10.6) 2.0 (3.4) 390.0 (25.8) July 2446 397.9 (26.1) 105.3 (5.0) 2.3 (11.0) 3.3 (3.2) 390.4 (25.3) August 2641 397.0 (24.8) 105.9 (5.0) 1.4 (9.7) 2.7 (3.6) 392.7 (26.6) September 2508 398.0 (26.1) 105.9 (5.2) 1.5 (10.0) 0.9 (3.1) 392.7 (26.6) October 242 393.8 (24.8) 105.8 (5.1) 3.0 (10.6) -2.0 (3.4) 391.2 (26.7)

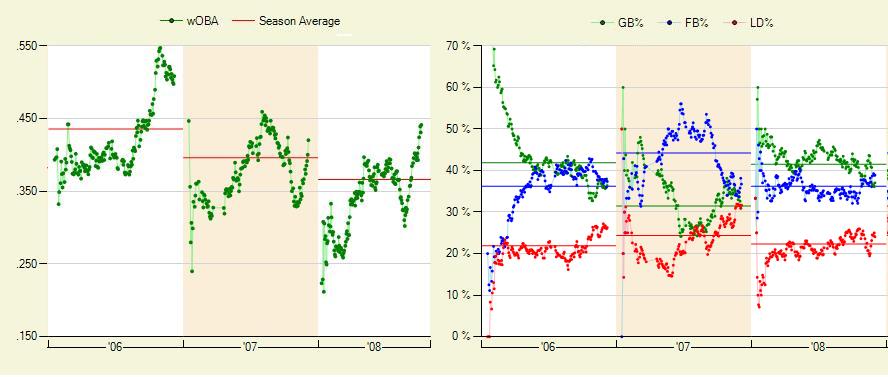

I wanted to do a mini-case study applying changes in home runs over time, and the clear choice for any such study is Ryan Howard. He gives us a nice sample to work with and such a large part of his value is built on home runs. He’s been on a clear decline since his age 26 season, so we can see whether there have been changes in his home runs year by year. Plus, if you look at his day-by-day graph on fangraphs, he’s been a rather remarkable second-half hitter.

Over his career, he's held a 168 point difference in OPS between the first and second halves of the season. I'm not predicting that he'll continue the trend this year—I'm just pointing out that the trend has existed.

Howard also intrigues me since I believe he might be the best opposite field power hitter of all-time. But that’s a subject I’ll tackle another time hopefully. Again I decided to forego the launch angles and stick to the effects of speed off bat, temperature, wind, and distance. Presented without much commentary:

It's evident that he's been hitting the ball with less force in recent years. I also like that you can easily see trend lines with positive slopes each year, confirming him as a late bloomer.

Wind impact appears to be random, but you can almost make out those parabolic curves in temperature impact. A power hitter might be prone to mid-summer surges thanks to those extra five to ten feet in fly ball distance from less dense air.

Not much notable. He averaged 403 feet in 2006, 406 feet in 2007, and 398 feet in 2008. Here's his table. It includes his home runs from 2006-2008 but is missing three from 2007. It should be read category mean followed by standard deviation.

Month Amount True Distance Speed Off Bat Wind Effect Temp Effect Standard Distance April 13 414.2 (27.3) 109.1 (5.1) 5.3 (12.5) -3.0 (4.3) 408.3 (28.9) May 29 394.9 (29.1) 105.7 (5.5) 3.4 (9.7) 0.5 (4.4) 390.1 (33.0) June 24 410.7 (32.9) 105.1 (5.2) 3.2 (11.4) 3.3 (2.8) 402.5 (30.9) July 28 398.1 (27.7) 107.7 (6.0) 2.8 (7.9) 3.0 (2.9) 391.2 (29.0) August 26 404.8 (30.8) 108.0 (6.9) -3.6 (13.2) 4.3 (3.0) 403.2 (35.0) September 30 400.2 (22.9) 106.4 (4.6) 1.0 (6.9) 2.1 (2.8) 396.8 (24.8) October 4 390.5 (25.0) 104.5 (6.5) 3.7 (4.5) -2.5 (6.3) 389.3 (32.2)

All data was obtained from Hittrackeronline.com. Interested parties may contact webmaster@hittrackeronline.com

| F/X Visualizations | March 23, 2009 |

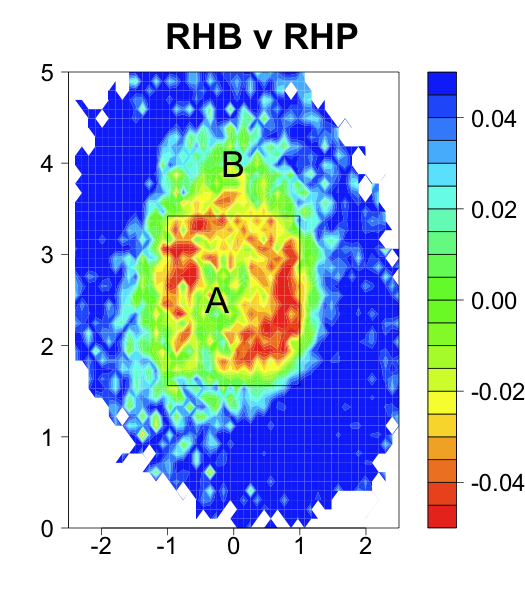

In a previous post I presented a map showing the run value of a fastball based on its location. In this post I will examine that map in more depth. Consider the two locations, A and B, in the figure below.

These locations have about the same run value, just below 0, but for different reasons. Taken pitches at location A are called strikes while taken pitches at location B are balls. In order for the two locations to have the same run value pitches swung at in location A must have, on average, higher run value outcomes than pitches swung at in B. Not brain-surgery so far, swinging at fastballs down the middle is better than swinging at fastballs a foot above the strike zone. We could try to intuitively guess at explaining the rest of the above pattern in a similar manner, but why try when we have the data to properly explain it. I will present that data in this post.

The run value of a pitch is determined by the outcome of four events.

- If the batter swings at the pitch or not.

- If no to 1, whether the taken pitch is called a ball or a strike.

- If yes to 1, whether the batter makes contact.

- If yes to 3, the run value of that contact.

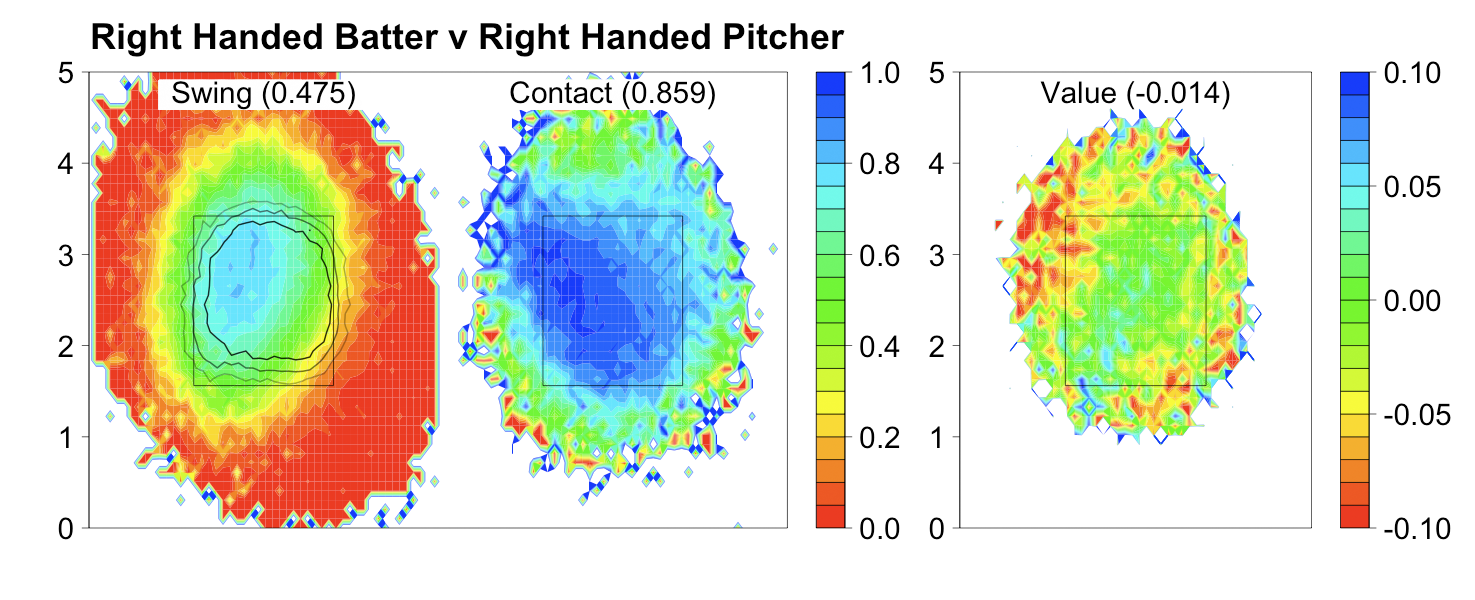

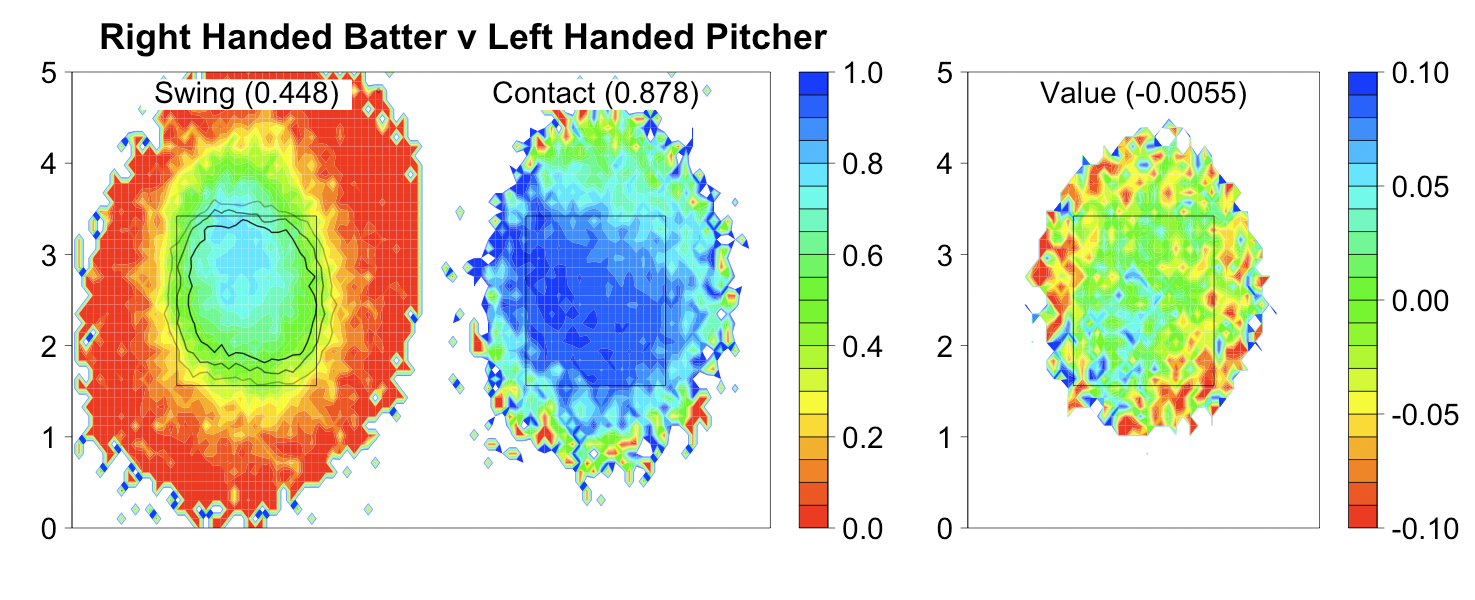

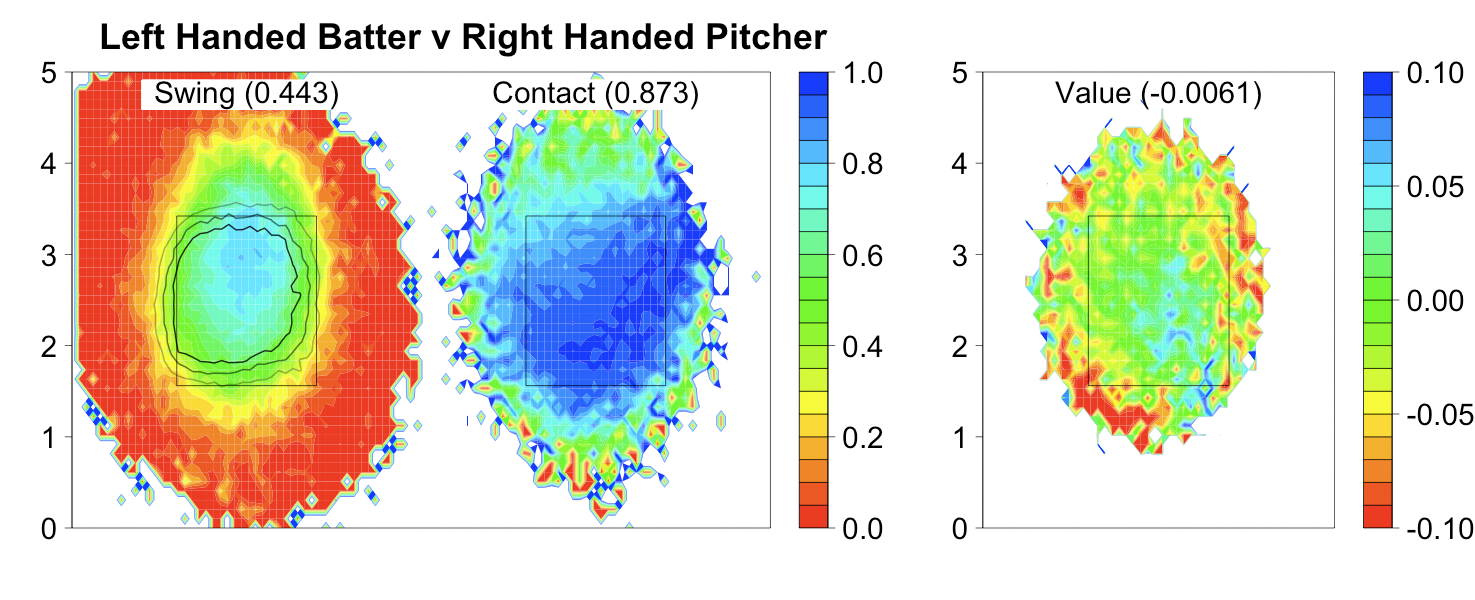

Below I present a series of three images for each handedness combination that show how the outcomes of these four events vary by location for fastballs. Reading left to right:

- The first image addresses events 1 and 2. The heat map is the swing percentage by location to address 1. On top of that are three contour lines where 75%, 50% and 25% of taken pitches were called strikes to address 2. So if a batter took a pitch inside the smallest circle it was called a strike over 75% of the time. If he took a pitch in doughnut between the smallest and middle circles it was called a strike between 75% and 50% of the time, and so on.

- The second image addresses 3 showing the contact percentage of pitches swung at.

- The final image addresses 4 showing the run value of a contacted pitch (including foul balls).

There is a lot going on in this series of images, and they might be intimidating at first. My suggestion is to focus on the leftmost image, spend sometime looking at it and once you understand it move on to the next. Do the same with the middle before moving on to the rightmost one.

With these images we can better explain the pattern in the overall fastball run value map. Consider location B in the first graph, the area of slightly negative run valued fastballs above the strike zone. Batters swing at pitches in this location over 50% of the time, make contact only around 70% of the time and the result of that contact is negatively valued. So the swung at pitches will have a quite low negative run value. The taken pitches are almost all called balls (this location is outside the largest strike contour) which have a very high positive run value. The result is the slightly negative value we see in the first image. Similar explanations can be made for any part of the run value map.

The region of highest swing percentage overlaps with the regions of highest contact percentage and run value of contacted pitches, and the 75% called strike contour, but is not entirely coincident with any of these. This means that hitters are not making entirely optimal swing decisions based on their ability to make contact, the value of that contact or how the strike zone is called.1

Contact percentage and run value of contacted pitches both reach their maximum slightly down and in from the center of the zone. But the overall regions of high contact percentage and run value of contacted pitches are not exactly the same. The region of high contact percentage is a diagonal swath from the top-in corner of the zone to the middle of the bottom of the zone. The region of high run value of contacted pitches is a diagonal swath from the bottom-in corner of the zone to the middle of the top of the zone.

Another interesting result is how the called strike zone compares to the rulebook strike zone. The inside and the top of the zone are called fairly well (the 50% contour runs along the rulebook zone on these edges), but the outside edge is shifted away a couple inches (the 75% contour runs along the rulebook zone's outside edge) and the bottom of the zone is shifted significantly up (the 25% contour is ABOVE the bottom edge). In addition, the strike zone is rounded rather than rectangular. These results are not new. John Walsh, David Pinto and Jonathan Hale have each shown all or some of these before, but it is nice to see that my analysis reproduces their results.

For the most part these are quite similar to the righty/righty images. One interesting thing we can address with these images is why RHBs do better against LHPs than RHPs. First, compare the location of the highest swing percentage relative to the strike contours in the RHB vs LHP and RHB vs RHP images. In the RHB vs LHP it is much more coincident along the horizontal axis, although it is still too high along the vertical axis . That means RHBs are swinging at more pitches in the called strike zone and taking more pitches outside the called strike zone against lefties than righties, which begins to explain their success. In addition, RHBs have a higher contact percentage and higher run value on contacted pitches versus LHPs compared to RHPs. So righties are better at each component of the at-bat against LHPs than RHPs.

These are almost mirror images of RHB vs LHP above and the overall averages are very close. It is interesting to see how the strike zone is called differently to LHBs. The top is called well and the bottom is called very high just like to RHBs. The outside edge is shifted away as it is to RHBs, but that shift is larger with the 75% contour extending outside of the rulebook zone. The inside of the zone is also shifted outside a couple inches (the 25% contour runs along the rulebook edge), which was not the case to RHBs. Walsh and Pinto also observed these results.