| Baseball Beat | May 29, 2009 |

Strasburg, Boras, and Everything Else You Wanted to Know About the 2009 Draft

When it comes to the First-Year Player Draft, nobody is as wired to what's going on as Jim Callis, the Executive Editor of Baseball America. He talks to general managers, scouting directors, cross checkers, area scouts, college coaches, and agents, gathering valuable information for Baseball America's website and biweekly magazine. With his ear to the ground, Jim's final mock drafts are routinely the most accurate published. Two months before I met up with Jim on a trip to Chicago in the summer of 2005, he predicted the first 18 selections of the draft in the exact order that they were taken.

Born and raised in Virginia, Callis graduated from the University of Georgia with a degree in journalism. He began his career with Baseball America in December 1988, left for STATS, Inc. in September 1997, and returned to BA in May 2000. In total, Jim has been covering baseball for more than two decades, including 18 years with Baseball America.

Born and raised in Virginia, Callis graduated from the University of Georgia with a degree in journalism. He began his career with Baseball America in December 1988, left for STATS, Inc. in September 1997, and returned to BA in May 2000. In total, Jim has been covering baseball for more than two decades, including 18 years with Baseball America.

Callis, 41, lives in the Chicago area with his wife and four children. In his spare time, he coaches his oldest son's 7th/8th grade baseball team. Like all of us, Jim is a baseball fan and his favorite team is . . . the Boston Red Sox! You can catch up with Jim about the draft, the Red Sox, baseball in general, and even pop culture in his online chats at ESPN Sports Nation.

Grab a cup of coffee, pull up a chair, and enjoy our discussion about the MLB First-Year Player Draft that begins Tuesday, June 9.

Rich: Hi, Jim. Thanks for taking the time to preview the 2009 First-Year Player Draft with us. How is this draft shaping up in terms of overall talent vs. those of the past?

Jim: It's not a good draft for position players, and it comes right after a draft that was loaded with hitters, so there's kind of a negative vibe about it. But there's talent in any draft. This one has plenty of pitching, college and high school, lefty and righty, whatever flavor you like, starting with arguably the best draft prospect ever in Stephen Strasburg. The college position players fall off a cliff quickly after North Carolina first baseman Dustin Ackley, but Ackley is a very good one. The high school position players are fine, with a lot of catchers and center fielders. It's kind of reminiscent of 2006, which was thought not to be deep in comparison to a hitter-rich 2005 crop, yet had Evan Longoria, Tim Lincecum, Joba Chamberlain and a host of other very talented players. So that's a long way of saying that there's talent in this draft, there's just not much consensus. I actually wrote a column on this, so I'll plug it here, though you need a BA.com subscription to read it.

Rich: The Washington Nationals are the first team to own two of the top ten picks in the same draft. The No. 1 overall choice is the reward for having the worst record in baseball in 2008 while the No. 10 selection is compensation for not signing Aaron Crow with the ninth pick last year. Aside from issues involving health, is there any chance at all that Washington would take someone other than Strasburg with the first pick?

Jim: No chance. Strasburg will be the No. 1 overall pick, barring injury. The track record of pitchers taken No. 1 overall is less than scintillating, but he's still far and away the best talent this year, and that's who you have to take with the top pick. He'll cost a lot of money, but far less than he would if he were on the open market. He also should be able to crack Washington's big league rotation almost immediately, if not immediately. There's no excuse for not taking him No. 1.

Rich: Is the $50 million price tag for Strasburg that has been floated out there simply a strategic ploy on the part of Scott Boras to reset the bar for No. 1s or do you think he will hold to something close to that figure at the risk of not getting Strasburg signed by August 15?

Jim: I'm sure Scott Boras believes in his heart that Strasburg deserves $50 million. I also believe that if all 30 teams could bid on Strasburg, he'd get that money. But the leverage to get that money doesn't exist because Strasburg's only options are to 1) sign with whoever picks him or 2) re-enter the 2010 draft. There's no avenue to free agency. If Scott doesn't get his asking price, he gives the team every chance to up its offer right up until the deadline. So don't look for Strasburg to sign before 11:59 p.m. ET on Aug. 15.

Rich: Nationals president Stan Kasten has been quoted as saying, "We know what No. 1s get and we intend to sign that player...No one's situation is going to change the industry." Doesn't that comment suggest the Nationals are going to draft Strasburg with the intention of offering him an eight-figure contract but much closer to the $8.5M-$10.5M that the top three signees (Mark Prior, Mark Teixeira, and David Price) received than the $52M awarded to Daisuke Matsuzaka, the comp Boras has reportedly used?

Jim: I think that's exactly right. To sign Strasburg, the Nationals need simply to figure out what's the lowest amount they can offer that will be too risky for him to turn down in the end. The draft record for guaranteed money is $10.5 million by Prior, and I'm guessing Washington will come in somewhere between $15 million to $20 million. Matsuzaka's price tag was artificially inflated by the $51.1 million posting fee Boston paid, and his situation isn't analagous to Strasburg's.

Rich: According to Jim Bowden, Crow asked for $4.4M and turned down $3.5M. Do you think he will get that type of money this year?

Jim: I heard Crow wanted $4 million at the end. Those negotiations were botched by both sides, who should have met in the middle at the deadline. I do think he'll get similar money this year, though he doesn't have a ton of leverage. There's no way he can really go back into the 2010 draft at this point. He's pitching well in indy ball, and first-round pitchers who have gone that route have done very well in the draft. He could get one of those $5 million major league contracts. Most teams probably wouldn't give him that much, but there always seems to be one club that will. I think he could go as high as No. 3 to the Padres or No. 4 to the Pirates.

Rich: The other Independent League wild card in this year's draft is Tanner Scheppers. How would you compare and contrast Crow and Scheppers and where do you see the latter going?

Jim: Scheppers probably would have been a top-10 pick last year if he hadn't hurt his shoulder. He hadn't bounced back by the time of the signing deadline for the Pirates to give him big money as a second-round pick. Scheppers has more arm strength, while Crow has more polish and a better health history. Scheppers came out of the gates stronger this spring, but they're pretty even now. They both should factor in the top half of the first round, possibly in the first 5-10 picks.

Rich: Let's talk about what Washington is likely to do in terms of its compensation pick for not signing Crow last year. After you posted your Mock Draft, Version 1.0 two weeks ago, acting Washington general manager Mike Rizzo contacted Baseball America, and said, "We do not have to take a signability pick. We’re going to take the best guy. We’re going to have 10 names up there on the board, and we’ll take the one we like." It seems to me that the Nats have to be careful this time around because they won't get another compensation pick if they fail to sign this particular draft choice. Agree?

Jim: They do have to be careful, because teams don't get compensation for failing to sign a draft pick they got as compensation for failure to sign another. Reading between the lines of what Mike said, they very possibly could take a guy they like but the industry doesn't value as highly as the No. 10 pick, and in that case they could use their leverage to sign him to a below-slot deal. I don't think they'll use the price as their main focus of their pick, but I also don't think they're going to roll the dice on someone like Donavan Tate if he's still there.

Rich: There is an important distinction between ability vs. signability. Which teams are most likely to pay over slot to get the player they want?

Jim: Last year, the industry spent a record $188 million on the draft and 26 of the 30 teams exceeded MLB's bonus recommendations on at least one player. I think teams in general will be more thrifty this year. But the usual suspects, particularly the Yankees and Red Sox, I'm sure will be willing to spend if a talented player falls to them. The clubs generally don't announce this, though.

Rich: How many players that could go in the first couple of rounds are being advised by Boras this year?

Jim: Several. Scott has arguably the best prospect in draft history (Strasburg), the best hitter in this draft (North Carolina first baseman Dustin Ackley), the best high school position player (Cartersville, Ga., HS outfielder Donavan Tate), arguably the best high school pitcher (Westminster Christian Academy/St. Louis righthander Jacob Turner), the best middle infielder (Southern California shortstop Grant Green) and the best college lefthander (Oklahoma State's Andy Oliver). Other top-two-round Boras advisees include Gainesville (Fla.) HS outfielder LeVon Washington, Kentucky lefthander James Paxton, Tennessee outfielder Kentrail Davis and Rocky Mount (N.C.) HS outfielder Brian Goodwin.

Rich: Are there any teams that flat out won't deal with Boras? If so, which ones?

Jim: There are, though everyone at least kicks the tires on his guys and no one will admit to avoiding his players on the record.

Rich: Has MLB sent out guidelines for slot money this year?

Jim: We had early indications that the slot recommendations will be the same as last year, but Murray Chass has reported that Bud Selig wants to roll them back by 10 percent, just like MLB tried to do in 2007. We've since confirmed that. Suffice it to say that no one is happy. I've had agents tell me there's no reason for a first-rounder to sign before Aug. 15, and I had one front-office official describe it as "fucking bullshit." You may edit that quote as you like.

Rich: Those aren't my words, Jim, so I think I'll leave that quote as is. Forget slot recommendations for a minute. Given the economy and the state of baseball, do you expect signing bonuses will be negatively affected at any point in the draft?

Jim: I don't think bonuses will be slashed, but I do think there will be fewer teams who will aggressively sign players for well above the slot recommendations. The last time MLB tried to cut slots by 10 percent, bonuses went up anyway, so I don't think that will have as much of an effect as the economy will.

Rich: Which players stand to get "out of the box" type deals and why?

Jim: Strasburg, obviously, because of his immense talent. The top college pitchers usually get major league deals with a $3 million bonus and a $5 million total guarantee, so that's may be what Missouri's Kyle Gibson and North Carolina's Alex White are looking for. Then again, they haven't lit scouts up down the stretch, so they may be more apt to sign for slot. I bet Ackley will seek a big league contract as well. The three top talents who could fall the most in the first round because of asking price are Tate, who has the leverage of a football scholarship from North Carolina, Turner and Klein HS (Spring, Texas) lefthander Matthew Purke. The numbers we're hearing on those guys are $6 million for Tate, $7 million for Turner and $5 million for Purke. There also are starting to be rumblings that the other elite high school lefty, Tyler Matzek of Capistrano Valley HS (Mission Viejo, Calif.), may not be an easy sign either. There's no number on him yet but teams are thinking he may prove costly.

Rich: The price tag on Turner seems to be based on what Josh Beckett and Rick Porcello received. Is Turner in that same league?

Jim: He's very good, arguably the best high school pitcher in this draft, but I don't think he's in the same class as Beckett and Porcello. He's not far off, but he's not as highly regarded as they were in high school.

Rich: Given Tate's talent and and how the Braves have leaned toward Georgia-based prospects in the past, it wouldn't be unreasonable to assume that he could be atop their board, if available at No. 7. However, management hasn't been known to pay over slot and, as such, do you think Atlanta will forgo Tate for another player who may not be as risky or costly?

Jim: The Braves don't usually draft Scott Boras clients. Their last prominent one was Joshua Fields, and that didn't work out too well. I would be very surprised if Atlanta took Tate.

Rich: Purke has signed a letter of intent to attend TCU and would be a draft eligible sophomore in 2011, which means he could have as much leverage in two years as he does this year. Although I have likened the tall, lanky lefthander with the three quarters delivery to Andrew Miller (not sure if that's as high of a compliment today as it may have been a few years ago), I see him as a gamble for most teams (other than perhaps the Texas Rangers or Houston Astros) at that price tag. Could he slide all the way to the Boston Red Sox at No. 28 or to the New York Yankees at No. 29, a la Porcello in 2007 and Gerrit Cole in 2008? Porcello turned out to be a great selection for the Tigers but Cole rejected the Yankees and opted to go to UCLA instead.

Jim: He could slide that far, sure. I think the Rangers could be tempted by him if Brownwood (Texas) HS righthander Shelby Miller is gone, and I'm not sure the Astros would go that far over slot if Purke holds true to his price tag. My guess is the Yankees would be more likely than the Red Sox to take Purke.

Rich: Let's circle back for a minute. Strasburg is off the board and it's now time for the Seattle Mariners to make their first pick (No. 2 overall). Is Ackley the consensus choice here?

Jim: I think he is. For a long time, the story was this draft was Strasburg and no consensus No. 2. Now I think most teams in the top 10 picks would pop Ackley if they had their choice (assuming Strasburg is gone, of course). I would do the same thing. I think he's a can't-miss bat, should have at least average power and will be able to move to center field. He's the clear No. 2 prospect in the draft for me.

Rich: Some might say that the draft doesn't really begin until the San Diego Padres make their selection at No. 3. Do you think management will take USC shortstop Grant Green a second time (14th round in 2006)?

Jim: I projected the Padres to take Green in my first projected first round two weeks ago, but now I'm hearing that while they like him more than any team in the top 10, he's not in the mix at No. 3. I've heard Tate there, but he doesn't seem to fit their type of guy as a less-polished high school athlete with a huge price tag. I've also heard Crow and Vanderbilt lefthander Mike Minor there, too. Crow would make more sense to me, but may cost more as well.

Rich: If Green slips past the Padres, where do you see him going?

Jim: He's a real wild card. I can't see Boras advertising him as a guy who signs for slot no matter where he falls, and he hasn't lived up to what scouts expected this spring. Maybe he falls all the way to the Yankees, who spent their first-round pick on another USC player under similar circumstances (Ian Kennedy) a few years ago.

Rich: Which players have been climbing the draft boards the most since you put out your Mock Draft a couple of weeks ago?

Jim: Minor is going to go very high after pitching very well in his last two starts, likely in the first 10-15 picks. We have him rated as more of an early sandwich pick, and I think that's where his talent fits, but he'll go higher than that. Of the projected first-rounders from two weeks ago, I think most guys' stock is holding firm for now. Signability may have guys rise or fall but talent-wise, I don't think anyone else is really leaping up. Guys like Lipscomb lefty Rex Brothers and Indiana righty Eric Arnett continue to pitch well, but we had them as mid-first-rounders to begin with.

Rich: Aside from signability issues, whose stock has been dropping the most — and why?

Jim: White hasn't pitched well recently. He entered the year as the No. 2 pitcher behind Strasburg for some clubs, but now I think he probably won't go in the first 10 picks. A lot of teams are backing off of Green. Even if he'd sign for slot, he might last until the middle of the first round. Baylor righthander Kendal Volz had a chance to go in the top 10 but his stock has been dropping steadlily and he might be more of a third-rounder now.

Rich: Are there any debates as to where two-way players are best suited?

Jim: The biggest debate would be over Plant HS (Tampa) shortstop/righthander Mychal Givens. He's very raw but very talented at both positions, and I think it's a 50-50 split on which way he should go.

Rich: The Arizona Diamondbacks have back-to-back picks at 16 and 17. Do you see them taking one hitter and one pitcher or doubling up? Either way, will money get in the way of how the club approaches these selections?

Jim: I don't think they'll do anything beyond take the two best players, even if they're both hitters or both pitchers. They pick again at 35, 41 and 45, so if they double up they could always shoot for balance later. Ideally, I think they'd take a high school bat and a college pitcher. That is a lot of picks to pay, and it remains to be seen if they'll take some money-savers early in the draft.

Rich: After not having a first-round pick in three of the last four drafts, the Angels own the 24th and 25th spots this June, as well as three sandwich selections (40, 42, and 48). How do you see owner Arte Moreno, GM Tony Reagins, scouting director Eddie Bane & Co. handling this year's haul?

Jim: The Angels aren't afraid to spend and their farm system is flagging a bit, so I'd expect them to pay full freight for all five picks. They love athletes and projectable pitchers, and they love to focus on players in Southern California.

Rich: With the 2nd, 27th, and 33rd picks, Seattle is also in a good position this year. How do you see the new regime approaching these choices?

Jim: When he was running drafts in Milwaukee, Jack Zduriencik took the best player available, not caring if it was college vs. high school, pitcher vs. hitter, or what the general consensus on a guy was. The system isn't loaded with arms, so they might lean a little more toward some college pitching after grabbing Ackley at No. 2.

Rich: OK, let's finish with a big surprise. It could be anything. Let 'er rip.

Jim: Hmmm . . . I guess something that has jumped out at me recently is how a lot of the expected best college pitching duos (Baylor's Volz and Shawn Tolleson, Oklahoma State's Oliver and Tyler Lyons, Stanford's Jeff Inman and Drew Storen and Kent State's Brad Stillings and Kyle Smith) have mostly fizzled, with the exception of Storen. Now the two best come from unlikely sources: Kennesaw State's Chad Jenkins and Kyle Heckathorn, and Indiana's Arnett and Matt Bashore. Jenkins and Heckathorn could both go in the first round, as should Arnett (who would be the Hoosiers' first first-rounder since 1966), and Bashore may sneak into the sandwich round.

Rich: Excellent. Thank you, Jim, for taking the time out of your incredibly busy schedule to share your expertise on this year's draft with us.

Jim: No problem. Love your website, and always glad to help.

* * *

Update: Jim posted his Mock Draft, Version 2.0 earlier today.

| F/X Visualizations | May 28, 2009 |

Last weekend Milton Bradley claimed that his strike zone had been expanded in retaliation for his early season run-in with umpire Larry Vanover.

This claim was brought to my attention in Craig Calcaterra's ShysterBall blog where he suggested that someone with "PITCHf/x-fu" could check this assertion. I am not 100% sure what "PITCHf/x-fu" is, but I like to think I have it. Either way I thought this was an exciting new application of the pitchf/x data, so I decided to take Craig up on it and see if Bradley's strike zone has been any different this year.Bradley believes his strike zone is being widened, forcing him to chase pitches he normally doesn't swing at or risk being called out on strikes.

Asked if there have been repercussions from Vanover's fellow umpires since the incident, Bradley didn't mince words.

"There always is," he replied. "No matter what, I'm the type of guy [where] I don't care what somebody does to a colleague of mine. I'm not going to treat him any differently. I do things straight up, because I'm a straight-up, honest individual.

"Unfortunately, I just think it's a lot of 'Oh, you did this to my colleague,' or 'We're going to get him any time we can. As soon as he gets two strikes, we're going to call whatever and see what he does. Let's try to ruin Milton Bradley.'

"It's just unfortunate. But I'm going to come out on top. I always do."

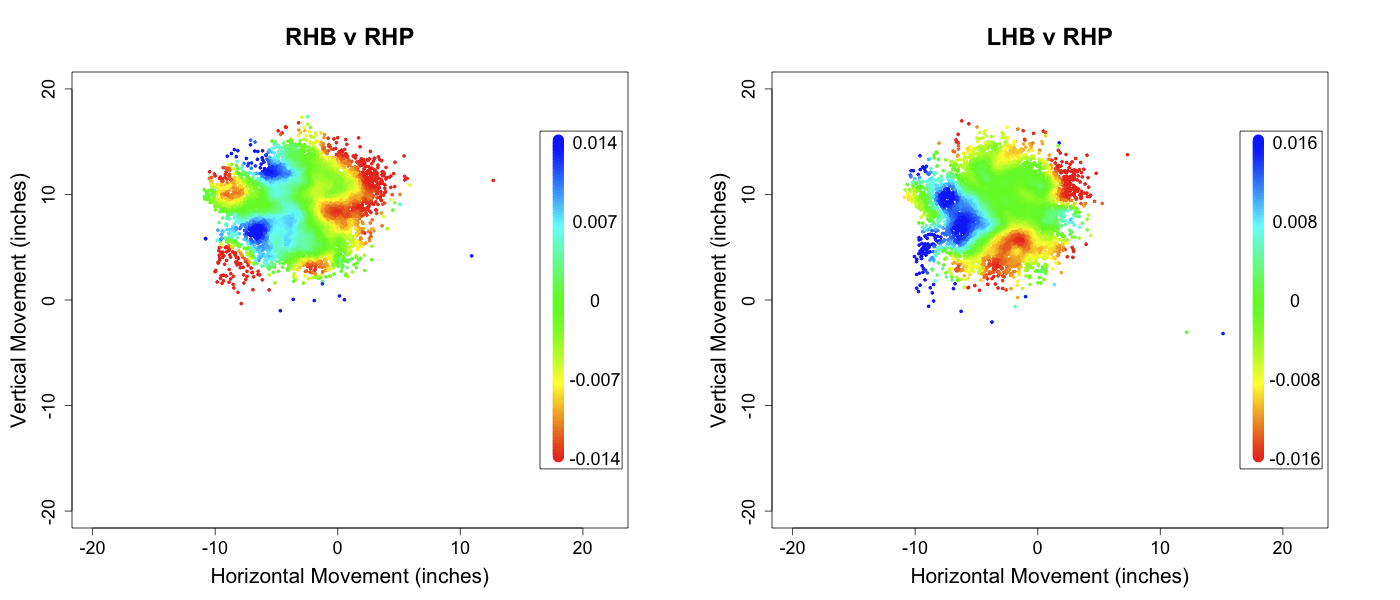

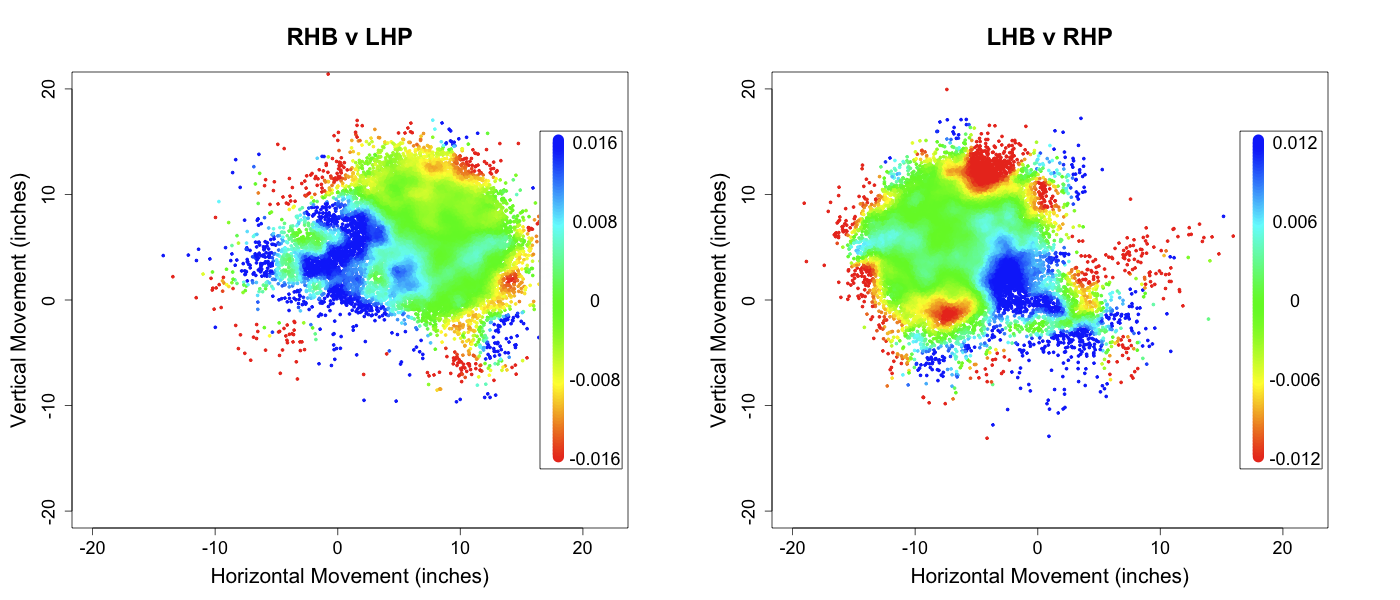

First off we need the smallest bit of background on the strike zone. It is called differently to right- and left-handed batters; the outside edge is extended out a couple inches to lefties. In addition, its size is count-dependent, expanding in hitter's counts and shrinking in pitcher's counts. These two facts make an assessment of Bradley's claims a little tricky. He is a switch hitter so we have to break up the analysis for him as a LHB and as a RHB. And any differences could be the result of differences in the fraction of time he is in hitter's versus pitcher's counts this year compared to the past.

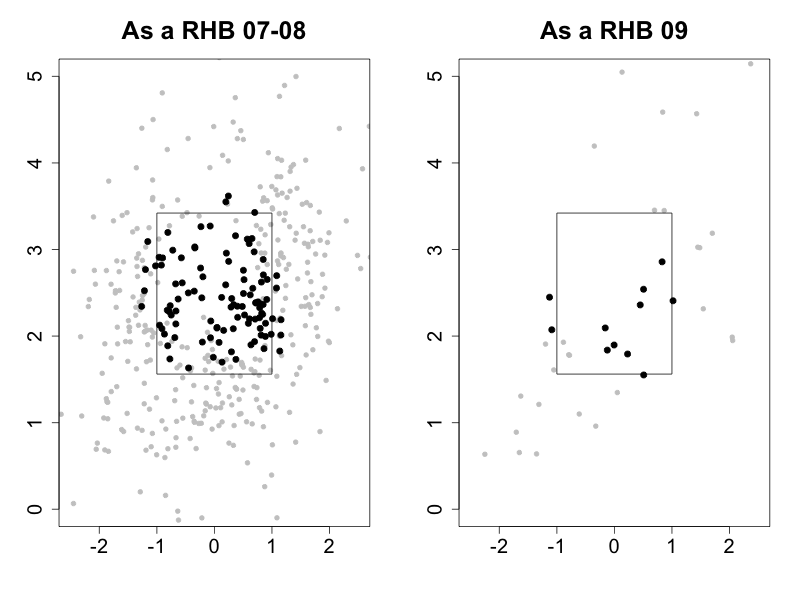

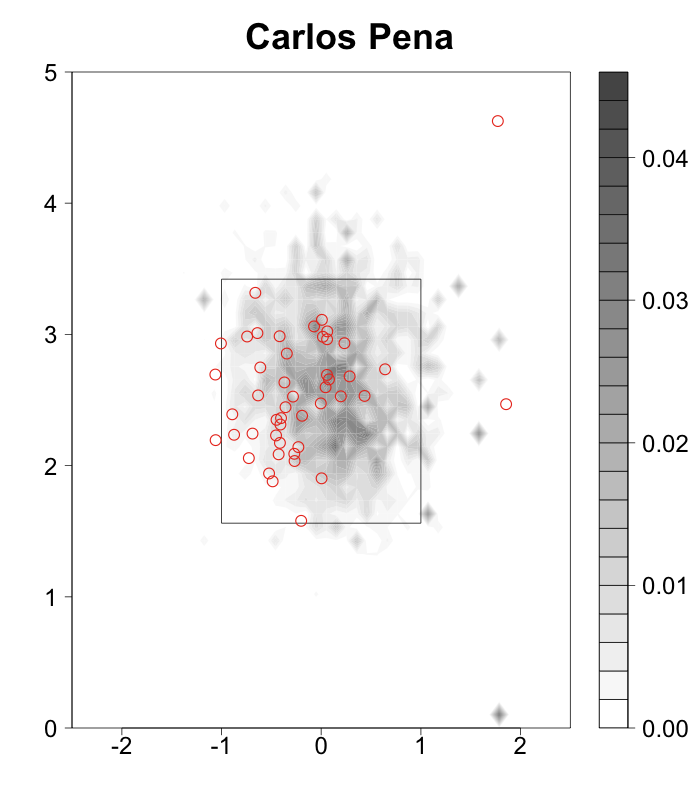

The pitchf/x system was phased-in in 2007 and has been operational in every game since, so I am going to compare pitches Bradley took in the part of 2007 covered and all of 2008 to those he took in 2009 thus far (ignoring the count issue temporarily). Here are the pitches he took as a RHB. Remember, the images are from the catcher's, so negative values of x are inside to a RHB and positive inside to a LHB. The gray dots are balls and the black dots called strikes.

There are too few taken pitches in 2009 as a righty to make much of a firm conclusion, but it does not look terribly out of whack. There are two called strikes on the inside edge, but right below them are four balls also along the inside edge.

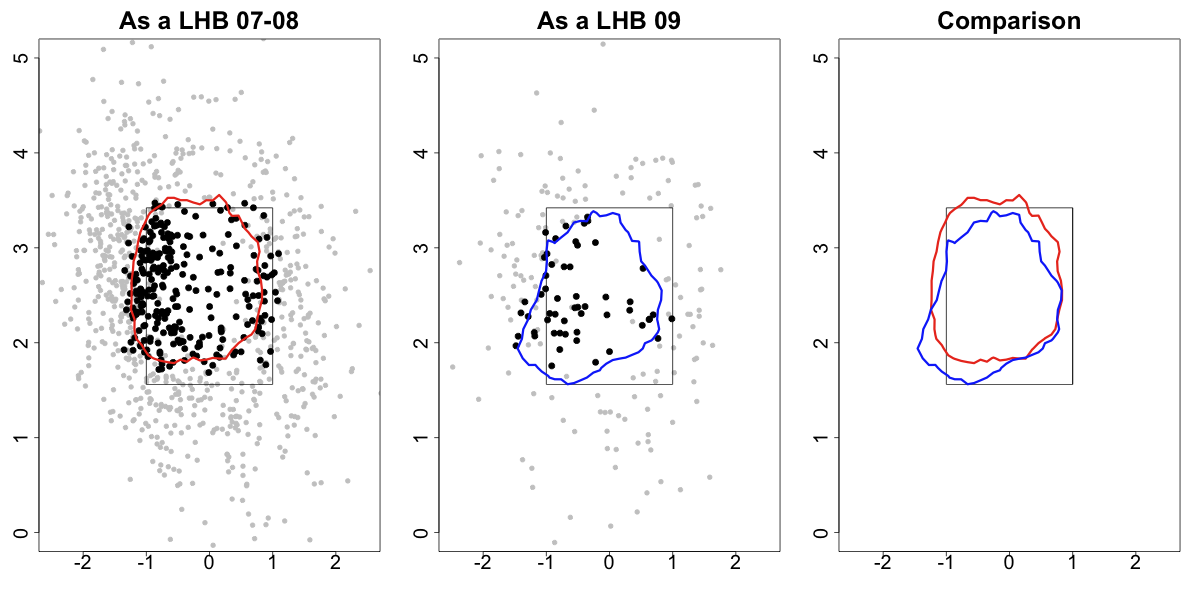

Here are pitches he took as a LHB.

Bradley has way more at-bats as a lefty and thus there are more taken pitches. These addition pitches allowed me to make called strike contours. These contours are closed lines such that a pitch inside the line is a strike 50% of the time or more and a pitch outside the line is a ball 50% of the time or more. Here you can see how the outside edge of the strike zone is shifted farther outside to Bradley as a lefty, as is the case to all LHBs. The inside edge of the pre-2009 and 2009 zones are almost exactly the same. Up and outside the pre-2009 zone is larger, but down and outside the 2009 zone is larger. As a whole the two are almost exactly the same size.

To make this conclusion statistically explicit, and correct for the count, I ran a binomial logistic regression. This is a regression in which the dependent variable only takes two values, in this case 1 if a taken pitch is called a strike and 0 if it is called a ball. The dependent variable is regressed against any number of ordinal and/or categorical variables. In effect this binomial logistic model uses these regressors to calculate the probability a taken pitch is called a strike, and tells you which of the regressors are statistically significant in determining that probability. The technique is identical to that taken in my earlier strike zone post, but this time I restrict the analysis to just Bradley's data.

I regressed Bradley's strike/ball taken pitches against the horizontal distance between that pitch and the horizontal middle of zone (with a different middle for Bradley as a LHB and RHB), the vertical distance from that pitch and the vertical middle of zone, the interaction of these two distances, the number of balls and strikes (to control for the count) and a categorical factor of pre-2009 or 2009.

Binomial Logistic Regression +-----------------+----------+------------+---------+------------+ | | Estimate | Std. Error | z Value | P(>|z|) | +-----------------+----------+------------+---------+------------+ | (Intercept) | 5.995 | 0.370 | 16.21 | < 2e-16 * | | x Dist. | -0.364 | 0.022 | -16.37 | < 2e-16 * | | y Dist. | -0.526 | 0.031 | -17.48 | < 2e-16 * | | x*y Interaction | 0.012 | 0.000 | 13.87 | < 2e-16 * | | Num. Strikes | -0.897 | 0.178 | -5.03 | 4.8e-07 * | | Num. Balls | 0.251 | 0.085 | 2.96 | 0.003 * | | 2009 | -0.023 | 0.217 | -0.10 | 0.914 | +-----------------+----------+------------+---------+------------+

Regressors with a negative estimate decrease the likelihood of a pitch being called a strike. So as the x or y distance increases the probability of a strike decreases, as expected. As the number of strikes increases the probability of a strike decreases (the strike zone shrinks in pitcher's counts) and as the number of balls increases the probability of strike increases (the strike zone expands in hitter's counts). All of these effects are strongly significant and mirror the results for all hitters.

The difference between the pre-2009 and 2009 zone is very slight, and if anything the 2009 zone is slightly smaller. Taken pitches in 2009, correcting for distance and count, are slightly less likely to be strikes. But this effect is very non-significant. There is over a 90% chance the difference between pre-2009 and 2009 zones is just due to chance alone. There is no statistical difference between Bradley's zone this year and his zone in 2007 and 2008.

I can understand Bradley was frustrated on Sunday. The Cubs had just lost seven straight games, and in five of those games they scored either zero or one run. He is hitting a meager .196/.322/.373 this season, but he has his decreased BABIP and LD% and increased GB% to blame for it, not the umpires.

| Change-Up | May 27, 2009 |

In looking into the San Diego Padres recent 10-game win streak, snapped last night in Arizona, I found wisdom where I would not ordinarily think to seek it. Save some insidery commentary about the sort of effect Petco has on visiting hitters that didn't seem to make a whole lot of sense, John Kruk was spot on in his analysis of San Diego's recent winning ways and what the implications are for the rest of the season:

People might want to make a big deal about the San Diego Padres winning 10 consecutive games, but I don't think it's that great a story yet. Their 9-7 win against the Arizona Diamondbacks on Monday snapped an 11-game road losing streak, and was only the fourth time this month they had scored six or more runs.The Padres are beset with offensive issues much like their NL West rivals, the San Francisco Giants. The Padres are anchored by an impressive 1-2 punch at the top of their rotation in Chris Young and Jake Peavy, while the back end is held down by closer Heath Bell. All they really have on offense is first baseman Adrian Gonzalez, who has quietly become one of baseball's best players.

That sounds about right. They cannot win on the road, they have one guy on the team who can hit and their starting pitching cannot muster any consistency. In Heath Bell, Luke Gregerson and Edward Mujica they seem to have found a core of reliable arms to build around in the bullpen but beyond their relief pitching, there are no discernible strengths on this club.

As good as he can be, Jake Peavy still has not regained his once dominant form. He has allowed 3 earned runs or more in 6 of his starts in 2009. Compare that to his Cy Young campaign of 2007 when he yielded 3 or more earned runs just 10 times all season long. His peripherals look sound and he has been excellent in May, however. He is still a bona fide, top of the rotation hurler but let's see how long he remains in San Diego.

As for the rest of the rotation, well, have a look for yourself.

IP H BB K K/9 K/BB ERA

SP ex Peavy 197.1 191 90 137 6.3 1.5 4.98

I don't need to tell readers here that a 4.98 ERA while pitching half of your games at Petco Park is not very good. And on the offensive side, it's a similar story. They are hitting .234/.314/.389 despite featuring the League's leading home run hitter. Were one to back out Gonzalez's contributions this season then you would be looking at a run producing attack on par with their banjo hitting neighbors up the coast, the San Francisco Giants.

Nonetheless the Padres find themselves just four games back in the Wild Card race. I don't think there's much reason for hope in San Diego, which is something the Arizona Diamondbacks and their fans had in spades coming into the 2009 season. 26 games into the season their ace is hurt, they have yielded 28 more runs than they have scored and they're 6 games under .500. Players in their prime the D-Backs need to produce continue fall short of expectations, and boy was the Eric Byrnes contract extension a mistake.

AVG OBP SLG

Tracy .189 .252 .342

Drew .190 .280 .333

Young .177 .219 .320

Byrnes .208 .257 .384

Still, as bleak as things seem I think there may still be hope for the Snakes. 21 year-old Justin Upton, hitting .325/.400/.617, has broken out. Same goes for the electric Max Scherzer, who had his best outing of the season last night. His ERA is down to 3.38 and he is striking out over a batter an inning. With Dan Haren once again pitching lights out, Brandon Webb coming back at the end of June and Doug Davis and Jon Garland playing their typical innings-eater roles, this is a rotation that can work.

But the offense has to come around, and there is good reason to think that it can. At Fangraphs, Dan Szymborski has published his ZIPS projections for the rest of the season, and here is how the quartet listed above looks according to his numbers:

AVG OBP SLG

Tracy .257 .315 .414

Drew .266 .323 .439

Young .231 .304 .454

Byrnes .254 .313 .425

They're not lighting the world on fire, but they look a heck of a lot better than how they have fared thus far in 2009. Along with the health of Webb, it is the play of these four position players that will determine the fate of the 2009 Diamondbacks.

As noted at the top, the Diamondbacks ended the Padres 10-game winning streak last night in Phoenix. Says here that it was the start of a trend for both clubs.

| Touching Bases | May 26, 2009 |

For Cleveland sports fans, I don’t know if any moment could top LeBron James’ game-winning three pointer from Friday night. Last night’s ninth-inning comeback by the Indians wasn't half bad.

For Tampa Bay fans, though, last night's game was of greater importance than its bullpen collapse. Last night, David Price made his first start of the year.

Pitching in five regular season and five postseason games last year, Price served as an instrumental part in the Rays’ playoff run. Nevertheless, Price retained his rookie eligibility, and the Rays, managing a surplus in pitching, opted to option the 23-year old southpaw down to AAA and keep youngsters Andy Sonnanstine and Jeff Niemann in the rotation as well as limit Price’s innings.

Following Price's phenomenal postseason performance, Josh Kalk penned everything you need to know about the man, who was named the second-best prospect in baseball (behind Matt Wieters) by Keith Law, Kevin Goldstein, and Baseball America.

In spring training, Price went 2-0 with a 1.08 ERA, but his six walks allowed in 8.1 innings of work were a bad sign. After Price’s second spring appearance, he admitted that he was experiencing difficulty.

"I've worked on my changeup so much, my slider's gone away," Price told mlb.com. "It's something I'm going to have to get back."

Considering the hype Price received, it's hard to believe that he still had areas where he needed to improve, but he's still just a kid with only a year of professional ball under his belt.

Price’s first six starts with AAA Durham were worrisome, as he posted a 1-4 record due to a disappointing 21:16 K:BB ratio. Price was drawing fewer swinging strikes and he was not inducing nearly as many ground balls in his 2009 stint with Durham as he had in 2008 across four levels. Yet Price seemed to have turned it around in the last couple of weeks leading up to his start yesterday. In what might be his final Minor League appearance of his career (knock on wood) Price went five innings of no-hit ball while striking out nine. Price entered the Rays' rotation when Scott Kazmir, to whom Kalk compared Price, hit the Disabled List. I set out to break down the second start of Price's Major League career.

Price came out firing. His first 14 pitches were four-seem fastballs clocking in between 94 to 98 miles per hour. Jamey Carroll drew for a leadoff walk, followed by Grady Sizemore hitting a pop up down the left field line, Carl Crawford made a futile attempt at a diving catch, which allowed runners to advance to second and third with no outs. Then Price really flashed his potential.

Price worked ahead of the count on Victor Martinez with fastballs, and with two strikes, Martinez had little chance. Price busted Martinez inside with sliders which Martinez could do little else but foul off. Price then blew Martinez away with a 98-MPH fastball on the outside part of the plate. Price worked ahead of Jhonny Peralta with inside fastballs and finished him off with a hard slider inside. Price finished the inning by testing Shin-Soo Choo with fastballs up in the zone, and on 2-2 Price threw a heater over the heart of the plate that Choo took for a called strike three.

Needless to say, that stretch was Price’s most impressive, which is fair since it doesn’t really get much better than that.

The Rays gave Price a fiive-run cushion heading into the bottom of the second. However, Price walked the leadoff batter on four pitches, which just makes you wonder. There’s no reason that any Major League pitcher with a five run lead should be walking the leadoff batter on four pitches. Price allowed five walks, which is the second time in his last four starts that he’s allowed that many. Walks have been a problem for Price. Since being promoted to AAA last year, Price has walked well over four batters per nine innings.

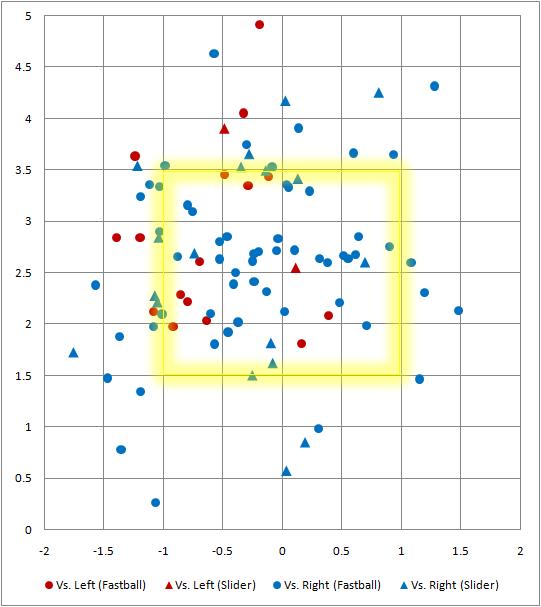

Let's take a look at Price's strikezone plot. This is from the catcher’s perspective, so pitches on the right are towards Price’s arm side, or inside to left-handed batters. Blue markers are pitches against righties, while red markers are pitches against lefties. Circles indicate fastballs while triangles indicate sliders.

It looks to me like he tried to work away from lefties. His off-speed stuff was saved almost exclusively for righties, and he tried to keep his sliders in on them. Looking at his strikezone plot, I don't think Price was wild, but he didn't shy away from working himself into long at bats, which is unnecessary given that defense behind him and his ability to blow batters away.

Despite the leadoff walk in the second, Price retired the next three batters in order. With a full count on Ryan Garko, Price demonstrated the ability to keep the ball in the zone when necessary, as he forced Garko to foul off five pitches in the zone before popping out on a slider on the outside corner.

Price allowed two more baserunners in the third, but came out unscathed. The fourth inning was where it all started falling apart for Price and the Rays. The Rays had a 10-0 lead, yet Price was already at 77 pitches by the start of the inning, and his fastballs to the first two batters of the inning were down in velocity to 92-94 MPH. Mark DeRosa lined a single the other way and Garko pounded his third homer of the year on a knee-high fastball. Price picked the velocity back up against Matt LaPorta, working at 95-97 with his fastball to strike LaPorta out. Yet Price was up at 90 pitches, and he had apparently lost his command. Price walked the next two batters and was pulled by Joe Maddon, who had said in a pre-game interview that it was a goal for Price to go deep into the game. Neither of those baserunners came around to score, but Price was fortunate to forfeit only two runs after allowing nine baserunners in 3.1 innings.

Price, as usual, was 95% fastball/slider. He showed his spike curveball and changeup once or twice, but they were all wasted for balls.

I’d say he found his slider. Like last year, it averaged a velocity of 86-88 miles per hour. While Price doesn't generate significant horizontal movement, he actually got the ball to dive more in yesterday's start than he did on average last year. He releases his slider a couple inches farther from his body than he releases his fastball on average. There aren't many sliders thrown at 86-88, especially from the left side. Last year, Francisco Liriano and Randy Johnson threw the hardest sliders among left-handers. Both of them had little horizontal movement, like Price, and Liriano's and Johnson's sliders actually generated less vertical movement than Price's has. Nevertheless, all of these sliders have solid reputations and they have all accounted for above-average run values, which can now be found on Fangraphs. Swinging at Price's slider simply isn’t a good idea. Out of eight swings on his sliders, there were five fouls, two misses, and one pop out. However, when batters took the slider, only two called strikes were called out of twelve pitches. If he can locate the slider down in the zone, I believe it would be nearly untouchable.

His fastball averaged 96 MPH, which, for a starter, for a lefty, and for a human whose arm must follow the laws of biomechanics, is positively exceptional. The movement on it is nothing to write home about, though, in my opinion.

Price’s stuff is unbelievable. There’s no denying that. But walking that many batters is inexcusable, and it cost his team the game. Price has yet to have an outing of over six innings since he was called up to the Majors last year. Part of that is due to the Rays’ attempt to limit his innings. And part of that is Price’s propensity to throw too many pitches. The Rays were forced to go to their bullpen early, and they ended up not having enough arms to close out the game. Well, that’s not really fair. A bullpen should be able to close out a ninth-inning seven-run lead. Here’s the WPA chart from the biggest comeback of the year.

| Baseball Beat | May 26, 2009 |

Over the weekend, the NCAA Baseball Committee announced the field of 64 teams that will compete for the 2009 NCAA Division I Baseball Championship. As always, there were a handful of surprises.

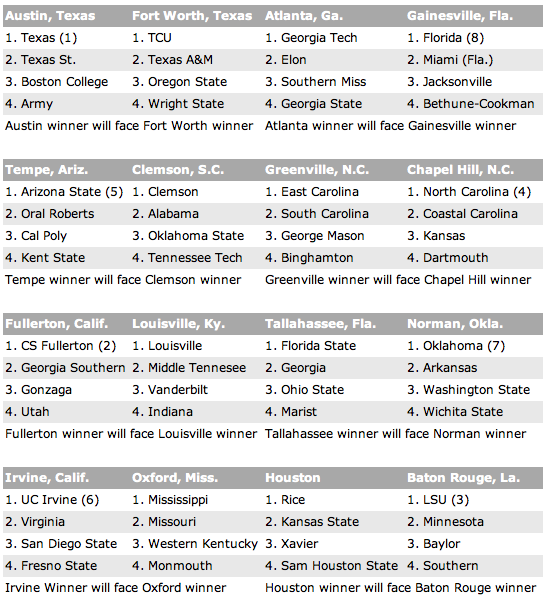

The Big 12 (Baylor, Kansas, Kansas State, Missouri, Oklahoma, Oklahoma State, Texas, Texas A&M) and Southeastern Conference (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, LSU, Mississippi, South Carolina, Vanderbilt) landed eight spots each while the Atlantic Coast Conference (Boston College, Clemson, Florida State, Georgia Tech, Miami (FL), North Carolina, Virginia) nabbed seven. Meanwhile, the Big West (Cal Poly, UC Irvine, Cal State Fullerton) and Pacific-10 (Arizona State, Oregon State, Washington State) garnered three each.

The Big 12, SEC, and ACC combined for 23 of the 64 available berths in the NCAA tournament. By comparison, the West (including the six schools named above plus Fresno State, Gonzaga, San Diego State, Utah) earned a whopping 10 spots or two more than the Big 12 or SEC. Mind you, the West sports the defending champ (Fresno State) and three of the top six national seeds (Cal State Fullerton, Arizona State, UC Irvine), yet is represented by less than 16 percent of the total field.

The top eight national seeds are as follows:

1. Texas (41-13-1)

2. Cal St. Fullerton (42-14)

3. LSU (46-16)

4. North Carolina (42-16)

5. Arizona St. (44-12)

6. UC Irvine (43-13)

7. Oklahoma (41-18)

8. Florida (39-20)

While Texas goes in as the favorite, it has been 10 years since the last No. 1 overall seed (Miami) won the College World Series. Along the same lines, no top-eight seed has emerged victorious since Rice in 2003.

Courtesy of Baseball America, the 64-team field is as follows (with Regional hosts listed No. 1 and national seeds indicated in parenthesis after the school name):

I'm all ears and eyes if anyone can explain to me how the Committee can justify placing UC Irvine (No. 1 ranked team in Baseball America's latest poll, the sixth overall seed, and the Big West champions), Virginia (No. 7 in Baseball America's poll and ACC tournament champions), Fresno State (defending NCAA champs and winner of the WAC tournament), and San Diego State (40-21 with a second-place finish in the Mountain West tourney) in the same Regional. The bracket is particularly unfair to UCI and Virginia, which gets the privilege of facing Stephen Strasburg, perhaps the greatest pitcher in the history of college baseball, in the opener on Friday night.

To be honest, it's hard to understand how Cal State Fullerton earned a higher national seed than UCI. The Titans finished five games behind the Anteaters in the Big West and lost the head-to-head series in early April. Granted, Fullerton (No. 1) has a higher RPI than Irvine (No. 18) but that should have little or no bearing when comparing two teams from the same conference that played an identical schedule in league and faced each other three times during the regular season. In any event, UCI gets Virginia, which could have conceivably been chosen as a Regional host, as its No. 2 seed and CSF gets Georgia Southern (unranked with the 35th highest RPI)? I'm sorry, but these pairings make no sense whatsoever.

Rice and Florida State can also make reasonably strong cases over Oklahoma and Florida for national seeds. As Baseball America's Aaron Fitt pointed out, "Rice was 21-9 against the top 100 teams in the RPI, and it finished strong by winning the CUSA tournament. And Florida State won the regular-season ACC title and reached the finals of the conference tournament."

Fitt also believes that "Oklahoma State is a horrendous, horrendous choice as an at-large bid." The Cowboys won just two of its nine conference series and finished ninth in a 10-team league, yet finds itself a No. 3 in the Clemson Regional. Baylor is another questionable call from the Big 12 (which is really the Big 10 when it comes to baseball).

The Regionals begin on Friday, May 29 and conclude on Sunday, May 31 (or Monday, June 1, if necessary). Selection of the eight Super Regional hosts will be announced on Monday, June 1 at approximately 11 p.m. ET. The Super Regionals will take place on June 5-7 and June 6-8. The best-of-three-games winners will advance to the College World Series at Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha, Nebraska on June 13-23/24.

Additional notes (from the NCAA press release):

* * *

Update (5/27/09): Boyd's World has posted its Iterative Strength Ratings (ISR)-based probabilities to determine the odds of winning the Regionals, Super Regionals, and College World Series. Not surprisingly, the 16 Regional hosts are favored to win this weekend with Texas (66.9), Arizona State (78.2), Cal State Fullerton (83.4), and UC Irvine (54.8) the only schools with a better than 50 percent chance of making it to Omaha. Based on these ISR findings, Fullerton (32.6), ASU (19.2), and Texas (13.2) are the three favorites to win it all.

| Baseball Beat | May 25, 2009 |

The Major League Baseball Draft will be held two weeks from tomorrow. The first day (Tuesday, June 9), which will consist of the first three rounds plus two compensation rounds, will be televised live by the MLB Network at 6:00 p.m. (ET). The draft will resume on Wednesday (fourth through 30th rounds) and conclude on Thursday (31st-50th rounds).

Baseball Analysts will live blog the draft once again, posting player profiles and comments as picks are unveiled. We plan to kick off our pre-draft coverage on Thursday, holding a Q&A with Jim Callis, Baseball America's resident draft expert. As in the past, we will also bring you interviews with several top prospects, including Tanner Scheppers, who returns to the draft this year after failing to sign with the Pittsburgh Pirates last summer. In addition, we will provide post-draft analysis, including Marc Hulet's shadow draft.

* * *

Two years ago, I interviewed Josh Vitters, who was selected by the Chicago Cubs with the third overall pick in the 2007 draft. Due to a nagging hand injury, Vitters' pro career got off to a slow start, hitting a combined .118/.164/.118 in 55 plate appearances over two levels (Rookie and Short Season). He bounced back in 2008, putting up a .322/.357/.495 line, mostly at Boise in the Short Season Northwest League. The 6-3, 200-pound third baseman is taking it to a new level in 2009, raking at a .355/.381/.612 clip at Peoria in the Low-A Midwest League. He had five consecutive three-hit games from May 14-19 and has slugged seven HR in his past nine games.

While Vitters is drawing rave reviews (landing atop Baseball America's Prospect Hot Sheet for the past week), he has drawn only three walks in 160 plate appearances. Look for the aggressive-hitting Vitters to get promoted to Daytona of the High-A Florida State League soon but keep an eye on his BB/SO ratio as an indicator of his upside potential.

* * *

I interviewed Kyle Skipworth, who Baseball America called "the best prep prospect at that position since Joe Mauer was the first pick in the 2001 draft," as part of our pre-draft coverage last year. Skipworth was taken by the Florida Marlins with the sixth overall pick and signed within a couple of weeks for a $2.3 million bonus. The lefthanded-hitting catcher has had a difficult time adjusting to pro baseball. However, his struggles in the Rookie League last year (.208/.263/.340) weren't atypical for a kid who had just turned 18 the previous March. Unfortunately, Skipworth appears to have regressed this season, hitting .174/.222/.294 at Greensboro in the Low-A South Atlantic League. Worse yet, he has struck out 44 times (with only seven walks) in 118 plate appearances.

More than anything, it just goes to show that scouting young baseball players is an inexact science and that some players develop more quickly than others while others never pan out. Only time will tell if Skipworth will become part of the first or second camp.

* * *

Remember Bryce Harper? Well, it's time to revisit the 16-year-old sophomore from Las Vegas High School. The Wildcats completed their 2009 season about ten days ago and, according to Baseball America, Harper put up the following statistics:

| AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | BB | SO | SB | CS | AVG | OBP | SLG | OPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 115 | 76 | 72 | 22 | 9 | 14 | 55 | 39 | 5 | 36 | 3 | .626 | .723 | 1.339 | 2.062 |

The numbers look like they came right out of one of those video games where you can rig the system by creating the best possible player in the world. But these stats are the real deal. Harper hit eight of his 14 HR in the final seven games and ended the season on a 23-game hitting streak. One can only wonder why any team would even pitch to him at all.

Harper won't turn 17 until October 1. In the meantime, there's no rest for the young. He is expected to play in a full slate of wood bat summer league games. I'm hopeful of watching him perform in the Area Code Games in Long Beach once again and will keep readers apprised of the progress made by the slam dunk No. 1 pick in the 2011 draft.

* * *

Meanwhile, in the here and now draft, check out the stats for a college pitcher out of San Diego State that you may have heard a little bit about:

| W-L | G | GS | CG | SHO | IP | H | R | ER | BB | SO | HR | BAA | ERA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13-0 | 14 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 102.0 | 57 | 15 | 14 | 19 | 180 | 3 | .164 | 1.24 |

The only question that remains is not whether Stephen Strasburg, who leads the nation in ERA and Ks, is taken first overall but how much he signs for ($10 million, $15 million, $20 million, $25 million, or the $50 million that the Scott Boras Corporation has reportedly floated out there)? Seeing that he is already on my fantasy baseball team, my hope is that he inks a contract well before the August 15 deadline and pitches for the Washington Nationals this year.

* * *

Patrick Schuster, the Mitchell HS (New Port Richey, FL) pitcher who jumped into the national spotlight when he threw four consecutive no-hitters this season, is projected by Baseball America to go in the fifth or sixth round of the June draft. Look for the lefthander with four pitches, including a fastball that ranges from 87-92 mph, to make good on his commitment to the University of Florida if he's not drafted higher than that. You can view highlights of his slingshot delivery and an interview on ESPN's First Take here.

* * *

The top two high school southpaws in this year's draft are Tyler Matzek (Capistrano Valley HS, Mission Viejo, CA) and Matthew Purke (Klein HS, Spring, TX). I was impressed with both when I watched them pitch back-to-back, 1-2-3 innings in the AFLAC All-American Classic on TV last August. They each struck out two batters. Matzek throws four pitches but relies on a fastball that hit 93 twice that afternoon and a sharp-breaking curveball while Purke's more electric fastball out of a three-quarters arm slot touched 95. The latter may be a tougher sign as he has agreed to attend Texas Christian and will be a draft-eligible sophomore in 2011.

* * *

Update: The links to organizational statistics in our sidebar on the left have been updated for the 2009 season. Thanks to Baseball-Reference.com, you can access any player's major or minor league stats with one click. Go to the section labeled Reference, choose a team, then click on either "Bat" or "Pitch" and you will be taken to that club's complete list of major and minor league hitters or pitchers.

Furthermore, we have also updated our sidebar for the 2009 Draft Order for the first round and supplemental round. This information is courtesy of Baseball America.

| Behind the Scoreboard | May 23, 2009 |

After the Mitchell Report was released last year, baseball hoped to put its steroid past behind it. However, with this year's allegations of Alex Rodriguez and Manny Ramirez both juicing, steroids are once again back on baseball's front burner.

How A-Rod and Manny's legacies will be tainted by steroid accusations remains to be seen, but one of questions for fans, baseball media, and hall of fame voters is how to treat alleged steroid users in the steroid age. While no player has actually been tried for taking steroids, all players stand in front of the court of opinion, and this court, fair or not, will determine a player's legacy.

While the list of players somehow connected with steroids has grown to over 125 according to Baseball's Steroid Era, some alleged users seemed to have escaped the taint and shame that comes with steroid use, while others have felt the full wrath of public scorn crash upon them. Watching a nationally televised early season game this year between the Cubs and Cardinals, the announcers lauded the amazing feel-good story of Rick Ankiel, the wild pitcher turned slugger, while conveniently not mentioning that he completed the transformation with the help of Human Growth Hormone. Ankiel had a prescription from a doctor and was not banned by Major League Baseball, but he still took HGH - it seems that he has been given him a pass where other HGH users have been vilified - at least according to Miller and Morgan.

But while no polls of fans' perceptions have been taken, it got me thinking about how tainted certain ballplayers were due to steroids. While a poll might be ideal, another measure of steroid taint might be how many mentions of steroids linked with a player are in the media. Another might be how often fans refer to a player as a steroid user. Where's one place that the media and fans intersect to provide commentary on baseball? The internet of course.

One way of measuring the steroids stain is by using the all-powerful Google. To get a player's baseline number of mentions, I put a player's name in quotes and searched for all references within the past year. Then, to measure the stain of steroids, I searched for that player's name with the word "steroids" next to it and took note of how many hits were found in the last year for that search. Dividing the number of hits for a player and steroids, by the number of hits for the player overall, gives an estimate of the "percent tainted" for a particular player. I limited the searches to references within the last year to eliminate hits for that player before the steroids were found, as well as to give the controversy time to calm down - we're not as interested in how widely reported the story was at the time it broke, but in how a player is perceived after some time has passed.

Obviously this is an inexact science - the number of hits change over time, and is subject to the unknown inner workings of Google. And of course, if you've ever searched for something on the internet before, you'll know that sometimes you might get results that don't result in what you want - a hit from a search of Ankiel and steroids might talk about Ankiel in one place and mention steroids in a totally different context further down the page. Ideally, we'd like to filter those out, but this method should still give a decently accurate results.

Another potential problem, was that if there was recent news on the particular player and steroids, this tended to give some bizarre results - Tejada was recently pled guilty to lying to Congress, so for a few weeks this led there to be more hits for Tejada and steroids than Tejada alone. Now that inconsistency seems to have gone away. I'm not sure how this happens, but it's reason for caution when there has been recent news surrounding a player. For this reason, Manny Ramirez and A-Rod are not in the table below - the verdict is still out on how their usage will affect their legacy. The data I present here is about a week or so old - hopefully things haven't changed much.

For what it's worth, here is the table of the "Percent Tainted" for the alleged or proven steroid users. It's not a comprehensive list, but covers the highest profile players along with their usage and the source of their allegations.

Is there a pattern that can explain why some players seem to be more tainted than others? Not surprisingly, it's Bonds that tops the list. He's followed by Palmeiro, Clemens, and Caminiti, all high-profile steroids cases to be sure. A few guys, Knoblauch, Hill, Neagle, are high on the list, but are probably more an artifact of the method rather than real public perception. These were players who were out of baseball and out of the public eye when their names surfaced in the Mitchell Report, leading to a high percentage of recent hits linking them to steroids. On the other hand, this didn't seem to affect Fernando Vina or David Justice, who were also out of baseball when the report surfaced, but their percentages were fairly low.

Of the other Mitchell Report guys, some players got off relatively easily. You don't hear much about Eric Gagne's steroid use, and the Google data backs this up, at only 19% tainted. Gary Matthews Jr. and Brendan Donnelly also seemed to get a pass from the public. Why I'm not sure, but my perceptions seem to match the Google data - the guys at the bottom of the list aren't guys you generally associate with steroids, even though there's evidence that they did them. Meanwhile, the guys at the top are the players I tend to link with steroids more readily.

Players that were simply rumored to have juiced, or were implicated via hearsay, were less likely to be judged harshly by the public. A guy like Bret Boone, who's numbers surely would indicate steroid user, but was implicated only by Jose Canseco, came in fairly low at 21%. Ivan Rodriguez and Magglio Ordonez were even lower. Puzzling is Canseco himself, who was 30% tainted - high but not as high as some others - even though he seems to have made his entire existence revolve around steroids.

At the bottom of the list is our man Rick Ankiel, who was found to have taken HGH, but claimed he had a good reason for it. The ESPN announcers weren't the only ones giving Ankiel a pass; it seems that most others did as well.

In general, it seems that the players who took a low profile - no lawsuits, no interviews, no public outrage - seemed to fare the best. Guys like Clemens or Palmeiro, admittedly bigger stars to begin with, tried to refute the claims and ended up high on the list. It also seems best not be linked with one of those guys - Andy Pettitte probably handled his situation as best he could, but being linked with Clemens assured his own use would be brought up time and time again. Ditto with Benito Santiago and Bonds.

While it's interesting to see the perception of players who have already been busted, we can use the same method to try to track which players - past and present - are most perceived to have taken steroids, even if no actual evidence or credible allegations have been made. This isn't a witch hunt, but rather simply taking measure of who the public suspects of possibly taking steroids.

For this, we must take additional steps of manually filtering out results that actually suspect a player of steroids vs. results that say, have a player commenting on steroid use without any implication at all. A search of Derek Jeter and steroids may turn up a lot of results, but they will be talking about him in relation to A-Rod’s use, not suspecting Jeter of steroid use himself. To do this, I manually looked at the first 20 hits and saw which were relevant suspicions, and which were not, and proportionally scaled back the "taint percentage." To be fair I also went back and did this for the proven steroid users as well, so the table above also reflects this methodology. It's not foolproof to be sure, and it's somewhat subjective, but it's a way to combat the above problem.

Below is a table of players who have never been actually reported to have used steroids, and their taint percentages. The list consists of big power hitters and a few other all-star type players - the type of player who usually falls under suspicion, or at least attracts the attention of fans.

The most suspected, but never proven, player of all is not surprisingly Sammy Sosa. He's always been a face of the steroid era, despite never having actually been linked to using them, and his percent tainted is larger than most players who actually have been proven to take steroids. The other biggest suspicions seem to be based largely on statistics, which makes sense in light of the lack of actual evidence. Brady Anderson, Luis Gonzalez, Andruw Jones, and Adrian Beltre all had bizarre seasons of extremely high or extremely low production, presumably leading to their steroid suspicion.

Still, the lack of hard evidence leaves these players well below the average taint of players with actual allegations against them. Among active sluggers, David Ortiz and Albert Pujols, who many regard as the greatest clean slugger, are not above suspicion either. As luck would have it, I was playing around with these numbers the day before the Manny Ramirez steroids story broke - he was pulling around 5% - which would have made him one of the more suspected sluggers in the game today.

Of course, these numbers are not hard and fast - a couple of wackos making baseless allegations can significantly increase the % tainted in the table above so there's probably a fairly large variance to these numbers - but of course baseless allegations are exactly the type of thing we are trying to measure.

While I'd really like to see a public opinion poll of baseball fans asking how much they thought a variety of players were helped by steroids, this admittedly flawed method seems to be a decent approximation for the public's opinion on many players. My main concern is my lack of knowledge about Google’s inner workings, and how these percentages might fluctuate based on unknown reasons. Still it’s pretty interesting to see how players stack up. It will be interesting as time goes on, to see how the perception of players change. For some the scandal may fade away, while others may be permanently branded as cheaters. The lists above may give an indication of which players will be which.

| F/X Visualizations | May 22, 2009 |

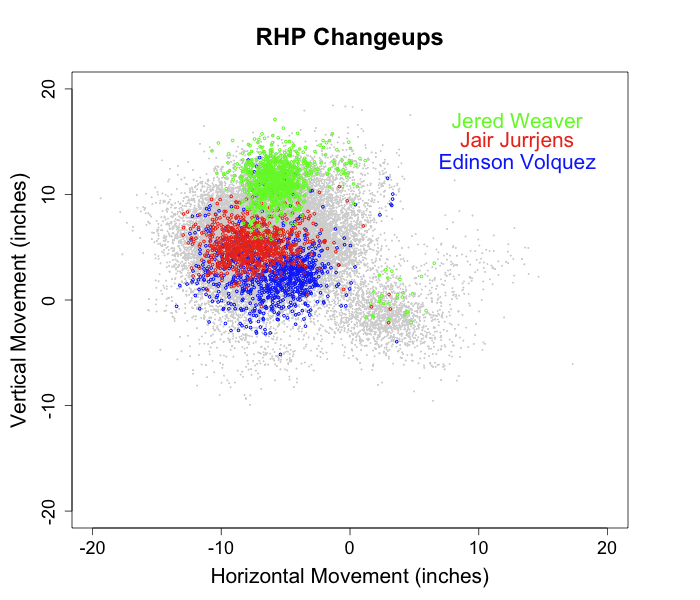

A large part of the success of a changeup is assumed to be based on its deceptive nature. Hitters expect a fastball based on the changeup's delivery and movement, but the pitch is about 10% slower. This throws off the hitter's timing, hopefully causing him to whiff or make poor contact. If this is the case we should expect the success of the changeup to be at least partially based on the difference in velocity between it and the fastballs that precede it. In this post I am going to examine this assumption. Is the success of a changeup tied to this difference? What is the optimal difference is speed?

Josh Kalk examined this question in a slightly different manner, looking at the relationship between the success of a pitcher's changeup over the course of a season and the difference in speed between his average changeup and average fastball. He found a linear relationship with increasing success based on increasing difference. I wanted to take a more granular approach and look at the success of a changeup based on the difference in its speed from the last fastball thrown to the batter, all the fastballs thrown to the batter in that at-bat and all the fastballs thrown to the batter in that game.

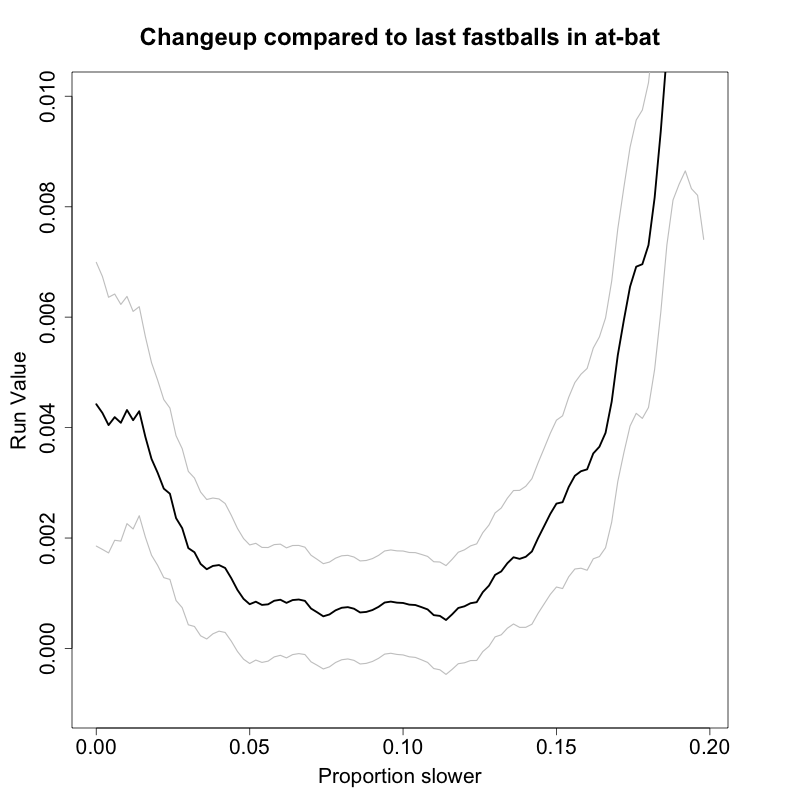

Here is the run value of a changeup based on how much slower (release speed) it was than the most recent fastball thrown to the batter in the at-bat the changeup was thrown. Changeups thrown before any fastballs were thrown in an at-bat were excluded from this analysis.

This suggests that the optimal changeup is between 5% and 12% slower than the previous fastball. The gray lines show the standard error. The results are similar if you compare the changeup to all previous fastballs thrown in the at-bat and all previous fastballs the hitter has seen in the game. The results are highly non-linear. There is little difference between throwing a changeup between 5% and 12% slower, but if it is less than 5% or greater than 12% slower the effectiveness rapidly drops off. This rapid drop off it not surprising; changeups that are too fast are effectively slow fastballs and changeups that are too slow don't look enough like fastballs. But, I am very surprised by how flat the graph is between 5% and 12%.

These results are seemingly at odds with Kalk's. He found that pitchers who average only 5 mph difference between their fastball and changeup over the course of a season have less successful changeups than those who average 10 or more mph difference. My results suggest that an individual changeup has about the same success if it is preceded by a fastball that is 5 mph or 10 mph faster. I am not sure how to reconcile these two different conclusions, but I am going to think about it more in the future and welcome any comments.

| Around the Minors | May 21, 2009 |

We've heard a lot recently about the excellent young pitching that the Giants organization is developing, and rightfully so. The team nabbed two excellent prep arms in the first round of the 2007 draft and both those players - LHP Madison Bumgarner and RHP Tim Alderson - were recently promoted to double-A Connecticut, just two small steps from the Majors.

But that's not all. The Giants organization has a plethora of young, exciting talent, which should be sustainable over the next eight to 10 seasons if the club plays its cards right. It's actually hard to believe how many good prospects there are, given the reputation that the team (and its management) had for almost laughably favoring aging veterans.

This isn't Dusty's team anymore. Or Barry's. With its electrifying mix of young hitting and pitching talent, it just might be the most dominating team in the National League for the next decade... beginning in 2010. Let's take a look at how dominating the San Francisco Giants could be even if it only fielded players originally signed/drafted by the club.

The Ace: Tim Lincecum

Drafted: 2006 1st round (University of Washington)

Born: 6/84 (24)

Pro Experience: Four seasons

MLB Experience: Two years

Notes: The club has about four seasons remaining before Lincecum will be eligible for free agency. Barring some terrible injury, there is no season to expect that the Giants won't lock up this talent long term. Lincecum is durable (227 IP in 2008), he's a proven winner (18 wins last year) and he's dominant (10.19 K/9, 7.5 H/9 MLB career).

The No. 2: Madison Bumgarner

Drafted: 2007 1st round (North Carolina high school)

Born: 8/89 (19)

Pro Experience: 1.2 seasons

MLB Experience: None

Notes: The kid skipped over short-season ball after being drafted and went right to A-ball. He then all but skipped over high A-ball en route to double-A at the age of 19. As an 18 year old, he led the South Atlantic League in wins, ERA, strikeouts and WHIP. The left-hander can touch 97 mph with his plus fastball and the secondary pitches are still improving, which is a scary thought.

The No. 3: Tim Alderson

Drafted: 2007 1st round (Arizona high school)

Born: 11/88 (20)

Pro Experience: 1.4 seasons

MLB Experience: None

Notes: Alderson has a funky delivery that worries some people, but he's always been durable and he has above-average control, as well as plus command of his fastball. He skipped right over low-A ball in his first full season and was one of the best pitchers in high-A ball. Alderson threw 6.2 innings of no-hit ball in his double-A debut recently, but he was pulled because he threw too many pitches while striking out 10 batters.

The No. 4: Matt Cain

Drafted: 2002 1st round (Alabama high school)

Born: 10/84 (24)

Pro Experience: Eight seasons

MLB Experience: 3.4 seasons

Notes: A 24-year-old pitcher that has thrown 200 innings twice and struck out 186 batters in 2008 would probably be a No. 2 or 3 starter for most teams. In San Francisco, though, he projects to be the No. 3 or 4 guy in terms of overall talent and potential. Cain walks too many batters (4.50 BB/9) but he's a durable innings eater. He's signed through 2010, but the Giants organization has an option for 2011, which will take him up until his first free agency year.

The Hopefuls:

Young pitchers Scott Barnes (9/87), a 2008 draftee exceeding expectations, and Clayton Tanner (12/87), a raw Australian hurler, are amongst the names vying for the one available rotation spot.

The Closer: Brian Wilson

Drafted: 2003 24th round (Louisiana State University)

Born: 3/82 (27)

Pro Experience: 4.2 seasons

MLB Experience: 2.1 years

Notes: Considering he was drafted in the 24th round, Wilson has come a long way and he's still developing as a closer despite saving 41 games last season. He's shaved almost 1 BB/9 off his walk rate and he's relying more heavily on a cutter to complement his 96 mph fastball and slider.

The Set-up Man: Henry Sosa

Signed: 2004 Dominican Republic

Born: 7/85 (24)

Pro Experience: 4.7 seasons

MLB Experience: None

Notes: Sosa has shown flashes of dominance in the minors, although he's also struggled with injuries. The right-hander is pretty much a one-pitch pitcher with a dominating mid-90s fastball. If he can improve his curve or change, he could be a closer candidate down the road. In his career, he's holding batters to a .190 average with runners in scoring position.

The Others:

Sergio Romo (3/83) doesn't have top-shelf stuff, but he knows how to use what he's got and he's quite adept at changing speeds. Waldis Joaquin (12/86) is a power pitcher with two potential plus pitches: a mid-90s fastball and a slider. Lefty Joe Paterson (5/86) is the epitome of a LOOGY; he's held left-handed batters to a .126 average and hasn't given up a home run while facing 168 batters (and striking out 67, or 13.11 K/9).

The Catcher: Buster Posey

Drafted: 2008 1st round (Florida State University)

Born: 3/87 (22)

Pro Experience: 0.3 seasons

MLB Experience: None

Notes: Posey went from being drafted 1,496th overall out of high school by the Angels to being taken fifth overall three years later after a solid college career. His time in pro ball has not been too shabby either, as the athletic catcher has a .300 career average. Posey has been creaming lefties to the tune of a .400 average in 40 at-bats. Not many teams can boast that they have a catcher who can hit .300 with 20 homers.

The First Baseman: Angel Villalona

Signed: 2007 Dominican Republic

Born: 8/90 (18)

Pro Experience: 1.7 seasons

MLB Experience: None

Notes: Villalona has moved across the diamond from third base to first base, but his power potential is more than enough for his new position. He's also hitting .314 in high-A ball, although the right-handed hitter is struggling against southpaws with a .225 average. Villalona also struggled against lefties in 2007, so it's something to keep an eye on. If he can learn to hold his own against southpaws, he could hit 30 homers in the Majors. Think David Ortiz in his prime, if everything clicks.

The Second Baseman: Emmanuel Burriss

Drafted: 2006 supplemental 1st round (Kent State University)

Born: 1/85 (24)

Pro Experience: 2.7 seasons

MLB Experience: 1.0 years

Notes: Burriss seized the bull by the horns with an unexpected opportunity last year and he's not looking back, although he did struggle early this season and hit only .182 in April. He's batting more than .400 in May, though. The switch hitter's base-running abilities are a valuable asset to this lineup. Burriss could even slide over to shortstop, his natural position, to make room for Nick Noonan.

The Third Baseman: Pablo Sandoval

Signed: 2002 Venezuela

Born: 8/86 (22)

Pro Experience: 6.2 seasons

MLB Experience: 0.5 years

Notes: With Bengie Molina blocking him behind the plate in San Francisco, Sandoval moved to the hot corner, where he's adequate defensively. Sandoval does not appear to be moving back behind the dish any time soon with Buster Posey on the way. The Venezuelan does not have the traditional power that one expects from a third baseman, but he hits for average and is a smart player. His best position is probably first base, but he cannot compete with Angel Villalona's total package.

The Shortstop: Brandon Crawford

Drafted: 2008 4th round (UCLA)

Born: 1/87 (22)

Pro Experience: 0.3 seasons

MLB Experience: None

Notes: Perhaps the biggest surprise of the 2008 draftees, Crawford was recently promoted to double-A along with 2007 draftees Madison Bumgarner and Tim Alderson. After two good college seasons, he slumped in his draft year when he was unable to get comfortable at the plate and had trouble repeating his swing. San Francisco has smoothed that out for him and his bat is now playing up (.353 career average in 150 at-bats), along with his defense, which includes a plus arm.

Left-Fielder: Roger Kieschnick

Drafted: 2008 3rd round (Texas Tech University)

Born: 1/87 (22)

Pro Experience: 0.2 seasons

MLB Experience: None

Notes: Another good-looking 2008 draftee, Kieschnick is the cousin of former two-way MLB player Brooks Kieschnick (Cubs, Brewers). The younger cousin has good power and has actually hit better than expected in pro ball, including an average above .300 at high-A ball in 2009. Kieschnick just needs to play with more control at the plate and stay back on breaking balls to keep the strikeouts down to a respectable level for a slugger.

Center-Fielder: Fred Lewis

Drafted: 2002 2nd round (Southern University)

Born: 12/80 (28)

Pro Experience: 7.5 seasons

MLB Experience: 1.8 years

Notes: The oldest of the position players on this roster, Lewis was a raw college draft pick that did not earn a full-time MLB gig until he was 27. The premium athlete has the skills needed to produce 20 homers and 30-40 steals, both of which could come with time. Originally a center-fielder, he could return to the position to make room for corner outfielders with more sock in their bats.

Right-Fielder: Nate Schierholtz

Drafted: 2003 2nd round (Chabot College)

Born: 2/84 (25)

Pro Experience: 5.6 seasons

MLB Experience: 0.5 years

Notes: The outfield projects to be the weakest area on the Giants team going forward, but there is some talent nonetheless and Schierholtz can flat out hit. He is a career .300 hitter with good, raw power that does not always show up in-game - but that can come with experience. Schierholtz has a very strong arm in right field.

Jackson Williams (5/86) may never hit more than .220-.240 at the Major League level, but his defense is more than good enough to warrant his inclusion on the roster of the future. Infielder Kevin Frandsen (5/82) was actually putting together a pretty nice career with the Giants before he missed almost all of 2008 after blowing out his Achilles tendon. Nick Noonan (5/89) was a supplemental first round pick in 2007 and is in line as the Giants' second baseman of the future. He'll have to wait his turn, though, with Burriss already holding down the fort. Outfielder Eddy Martinez-Esteve (7/83) was considered a top prospect at one time, but injuries and defensive inefficiencies have all but extinguished that talk. He still possesses a solid bat, though, and could be an excellent pinch hitter.

| Change-Up | May 20, 2009 |

Last night the Boston Red Sox defeated the Toronto Blue Jays 2-1 to pull within 2.5 games of the division leaders from north of the border. The story of the game was the return to the lineup of one David Ortiz, who had sat out the entire Red Sox series in Seattle over the weekend. The Boston faithful stood and cheered wildly in support of Big Papi each time he came to the dish. Chants of "Papi" and standing ovations, however, couldn't seem to pull the big slugger out of his slump (sleepwalk? death march?).

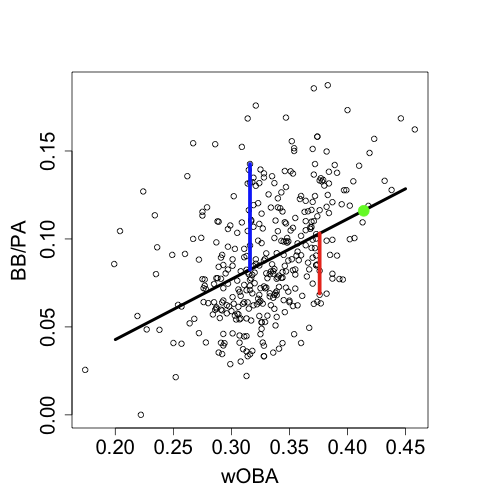

He was 0-3 with two strikeouts and two men left on base. Ortiz is now batting .203/.317/.293. His wOBA of .279 trails all but Ty Wigginton among American League Designated Hitters. While it would be nice to chalk Papi's problems to a mere slump, something that will work itself out - it's only May 20 after all - it's becoming difficult to imagine a return to form for Ortiz. We saw chinks in the armor last post-season when Ortiz, one of the most celebrated clutch performers in baseball history, managed to hit just .186. His bat has been slower, his approach clueless for some time now.

Despite this, Boston finds itself just four games out of the best record in all of Major League Baseball. All the while, Daisuke Matsuzaka, Kevin Youkilis and Dustin Pedroia have battled injuries, Jed Lowrie has been out for almost the entire season and Josh Beckett and Jon Lester have posted ERA+ figures of 85 and 77, respectively. Brad Penny has been worse than both of them. Boston's starting pitching ERA is 5.76, tied with Baltimore for very worst in the American League.

Fortunately for the Red Sox, there is reason to believe things will get better on the pitching front. If you're to believe Fielding Independent statistics, Lester and Beckett have been among the unluckiest pitchers in baseball. Both hurlers' peripherals look solid. Moreover, Youkilis returns to the Boston lineup tonight and Matsuzaka makes his first start since April 15th on Friday night. All around their Designated Hitter, things are looking up for Boston.

Working in their favor, it's not like the Red Sox have no recourse for dealing with their little Papi problem. Their pitching depth is the envy of Major League Baseball. That so many quality pitchers sit in the organization, many without prominent or even Big League roles, borders on absurdity. This is particularly so in the presence of a gaping hole at DH. Let's run through Boston's pitching depth.

How would this starting rotation look?

IP H BB SO ERA

Masterson 41.1 45 14 35 4.57

Penny 36.1 45 16 20 6.69

Buchholz (AAA) 39.1 23 12 42 1.60

Bowden (AAA) 42.0 19 16 28 0.86

Tazawa (AA) 43.1 38 13 42 3.12

It might not light the world on fire, but it would probably stand up favorably to how Boston's starting pitching unit has fared to date (remember the 5.76 ERA), a unit good enough to stake the Red Sox to a 23-16 record. This rotation, the one that might improve upon the 23-16 team's pitching to date, would leave Beckett, Lester, Matsuzaka, Tim Wakefield and John Smoltz out of the mix. Assuming Smoltz's rehab goes as planned (his rehab clock will be set to expire June 19), Boston would have ten quite legitimate Major League starters.

The depth is even more ridiculous in the bullpen. Prior to the season, in Fort Myers, Bill James told me that the Red Sox had the best bullpen on paper that he had ever seen. He was also quick to caveat that the best bullpen on paper means next to nothing given the unpredictability that comes with forecasting 50-80 innings worth of pitching. Still, James's commentary has proven prescient. Even with Masterson sliding into the rotation, Boston's 3.00 bullpen ERA trails only Kansas City's in the American League.

Jonathan Papelbon, Ramon Ramirez, Hideki Okajima, Manny Delcarmen, Takashi Saito and Daniel Bard are all worthy of pitching high leverage situations right now. And remember, with Clay Buchholz dealing in Pawtucket, Dice-K coming back and Smoltz beginning his rehab, that means there will be another relief arm or two whom Terry Francona can feel comfortable using in a big spot. At the very least, you can add Justin Masterson to that mix. Assuming good health, here is what the Boston pitching staff will probably look like one month from now:

Starters

Beckett

Lester

Matsuzaka